The Friendly Farmer Stations

By John Schneider, W9FGH

www.theradiohistorian.org

Copyright 2011 -

John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC

(Click on photos to enlarge)

Several postcard

views of the

KFNFstudio building

Studio building floor plans

Postcard views of the Henry Field Seed Company grounds

Some postcard views of "Mayfair", the KMA studio building.

Interior views of the Mayfair auditorium

Two views of the Gurney Seed Company buildings

WNAX transmitter building, 1936

Shenandoah on the air - WOAW:

In the beginning years of radio broadcasting in the 1920s, the rural Midwest was home to a number of unique and quirky radio stations that enjoyed wide attention and listenership. The story of Doc Brinkley’s KFKB in Kansas is one well-known example. Others include Norman Baker’s KTNT in Muscatine, Iowa, and WOC at the Palmer School of Chiropractic in Davenport. Then there were the Friendly Farmer stations, KMA and KFNF, of Shenandoah, Iowa.

In the beginning decades of the last century, the small town of Shenandoah (pop. 5,000) was the mail order seed and nursery capital of America. There were more than ten active nursery companies operating from the fertile valleys of Southwest Iowa. One of those was the Henry Field Seed Company. Henry Field, the company’s owner and namesake, was a plain-spoken, informal area farmer who had developed his burgeoning seed business from scratch, starting in 1899. By 1923, his business had grown to employ 600 people housed in a three story brick building on the north end of Shenandoah.

In 1923, Field was part of a group of Shenandoah citizens who travelled to nearby Omaha to promote their hometown over station WOAW (later WOW). The live program consisted of old time fiddle music, hymns, and a talk by Field about the advantages of living in Shenandoah. It proved to be popular with the WOAW audience, and so the station invited the group to come back, and they made several more trips to Omaha in the ensuing weeks.

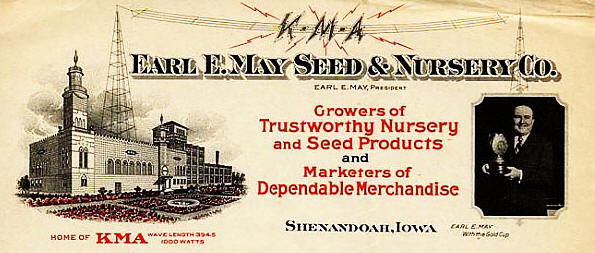

Another one of the participants in the WOAW programs was Field’s biggest local competitor, Earl May of the May Seed Company. May moved to Shenandoah in 1919 and bought out the small Armstrong Seed house operation. He had a friendly, folksy personality that appealed to the area’s farm customers, and he expanded his business by hawking seed, baby chicks, canned and dried fruits and frozen fish.

It didn’t take long after broadcasting the weekly programs on WOAW before both Field and May were bitten by the radio bug. They recognized the potential for for promoting their own businesses with the wide reach of the amazing new communications medium.

KFNF:

Field was the first to take action by constructing his own radio station in Shenandoah. He raised two 218 ft. towers adjoining the Field seed house to support a horizontal wire antenna, and installed a new 500 Watt transmitter in the building. On February 24, 1924, the first broadcasts were heard from KFNF, the “Friendly Farmer Station”. Field’s programs featured talks on agriculture and poultry, “old time music”, religion and folksy homespun philosophy, and Field himself was KFNF’s main announcer. With the relatively uncrowded radio bands and static-free nights of radio’s early years, KFNF’s signals were heard clearly throughout Iowa and the adjoining states. Midwest farmers liked his homey “Missouri English” colloquialisms and friendly manner, and they felt comfortable ordering merchandise from a radio voice they felt they could trust. The result was that his mail order business grew quickly, stimulated by its newfound radio fame.

Three blocks away, Earl May sat in his office contemplating his competitor’s success. He was still making the long and sometimes arduous trip to Omaha for the WOAW broadcasts each week, but he needed a physical radio presence in Shenandoah. So in June of 1924 he installed a remote studio in the May Company building as an origination point for his WOAW weekly broadcasts, connected with Omaha over a 66 mile telephone line.

With the expanded schedule of Shenandoah programs on both stations, the musical and speaking talents of as many of Shenandoah’s citizens as possible were paraded in front of the microphones. There were fiddling contests, religious services, talks on agricultural topics, and live music by such groups as the “Cornfield Canaries” and the “Seedhouse Girls”. In reality most of the performers were drawn from the staff of the seed companies themselves.

The mail order seed and poultry business of both companies quickly grew as a result of their new radio publicity. With his own station, Field was the biggest benefactor. Tourists from the area started arriving in Shenandoah to see the radio station and meet the people behind the faceless voices they heard nightly through the clear Midwest Air, and so Field began conducting regular tours of KFNF and his seed company. And his business boomed. In 1927, his company sold 55 carloads of tires, 60 carloads of paint, 490,000 pounds of coffee, 20 carloads of dried fruit, 51,000 radio tubes, 204,000 yards of dress goods, 60,000 pairs of ladies stockings and 21,000 suits. He even started selling his own brand of “Henry Fields Shenandoah Super Six” radio receivers.

KMA:

Finally, upstaged by the greater success of his competitor’s fully functioning broadcast station, Earl May decided that his remote broadcasts were no longer good enough. In the spring of 1925, he applied for and received a license to build his own 500 Watt station. The first broadcast over KMA was heard on Sept 1, 1925, and in the week that followed, 175 people performed in front of the KMA microphones for the dedicatory broadcasts. Initially, May broadcast for only a few hours a day, sharing his frequency with another station in Le Mars. (KMA and KFKN later shared time on the same frequency before each received its own full-time channel.) Nonetheless, in its first few months, KMA received reception reports and telegrams from all 48 states, Hawaii, New Zealand and Australia. KMA called itself "The Corn belt Station in the Heart of the Nation”. And the radio formula that had been so successful for Henry Field quickly worked its magic on Earl May. The distribution of his mail order seed catalogs increased by a million names in KMA’s first year on the air, and his business soon grew to over a million dollars a year.

The two little radio stations were turning Field and May into well-to-do businessmen, and the two seed companies were putting Shenandoah on the map. Both stations were being operated as publicity organs for the seed companies, and they carried little or no direct advertising. All programs were live, featuring homespun, country entertainment and information. Both nighttime signals reach out across the Midwest and the stations developed a huge following. In fact, in 1925 Henry Field won Radio Digest magazine’s popularity contest that declared him the “World’s most popular announcer”, beating out big city names like Graham McNamee for the honor. Earl May won the same award the following year.

About 1926, the dirt highways leading to Shenandoah were finally paved, making it possible for more people to drive to the tiny Iowa community to do business in person with the famous seed houses. Both stations were now conducting tours on a regular basis. In 1926, the stations recorded a combined total of 40,000 visitors.

Shenandoah's Radio Palaces:

Henry Field’s response to this new throng of visitors was to build his own KFNF studio building - a one story Spanish stucco building at the south side of Henry Field Seed House Number 1. The new KFNF building featured an auditorium where visitors could sit in pew-style benches and view the broadcasts in the large draped studio through a plate glass window. A dining room and kitchen in the rear was used for serving coffee and sandwiches to visitors. Both stations soon installed grand pianos and large pipe organs in their studios for live music broadcasts.

Not to be outdone by his competitor, Earl May constructed an even larger and more elaborate auditorium studio across the street from his seed company headquarters. The massive Mayfair auditorium was decorated in a Moorish motif with two minaret towers. The auditorium seated 1,000 people, and the studio/stage was separated from the audience by a 7 x 22 ft. sheet of glass weighing three tons that could be lowered into place to provide sound isolation. It was thought at the time to be the largest single sheet of glass ever made. The theatre was decorated in the style of a Moorish garden, with miniature electric lights in the blue ceiling canopy giving the impression of a starry night sky. May’s investment in KMA now totaled $90,000 for the station and another $100,000 for the auditorium. His operating costs exceeded $1,000 a month with no advertising revenue. All of this was supported by his booming catalog seed business.

Visitors were now flocking to Shenandoah by the thousands every week to see the live broadcasts and tour the radio stations and seed company warehouses, and they left carrying souvenirs, catalogs and lots of merchandise. The few hotels in town soon filled to capacity, and so Field built a row of cabins to provide additional housing for the visitors. Field also constructed an arcade shop, soda fountain, and even a KFNF filling station to accommodate the visitors. Meanwhile, May built a miniature golf course called Mayfairways. Both companies established branch trading post stores in Shenandoah and many other communities around the Midwest. They sold seed, poultry, cream, eggs, and general merchandise of all kinds. Earl May opened thirteen “Trading Post” stores around the Midwest, while Field opened seven stores in other cities. And all of this thriving business was being driven by radio.

Each station also celebrated a Shenandoah fall “Jubilee” weekend, which drew huge crowds to watch the live radio broadcasts and eat free pancakes. The KMA Radio Jubilee started in 1925 and took place every year into the early 40’s. Its first jubilee drew 25,000 visitors, and the following year the Earl May Seed and Nursery Company’s business quadrupled. KFNF frequently held its Jubilee on the same weekend as KMA, which grew into a super festival with carnival rides and exhibits. By 1930, the attendance had grown to 439,200.

Decline:

Radio in the twenties had turned this small Iowa village into a boomtown, but the 1930’s were another story as the Great Depression began to weigh on Midwest farmers’ businesses. The Jubilee attendance fell to 85,000 in 1933, and it remained at that level for the remainder of the decade. Henry Field’s large stocks of merchandise became devalued, and his radio catalog orders fell precipitously. Unlike the early years, the radio dial was now full of stations hawking products of all kinds, and the Shenandoah stations were no longer a novelty. Bonds which Field’s company had issued in 1930 to finance his business were foreclosed on in 1933. He lost control of the seed company, which was reorganized as the Henry Field Seed and Nursery Company, but continued in the role of president of the seed company and radio station even after his retirement in 1938. For his part, also needing new capital, Earl May sold 25% of KMA in 1939 to the Central Broadcasting Company, which owned WHO in Des Moines and WOC in Davenport. A new corporation was formed, May Broadcasting Company, to separate the radio and seed businesses.

Earl May died in 1946, and the operation of KMA was turned over to other May family members. Their descendants continue to successfully operate both the radio station and nursery to this day. Henry Field died in 1949. At the time of his death, his company had regained its prominence and grown to annual sales of over $3 million a year. It was sold and merged several times in succeeding years, but still operates today under the same name as a part of Scarlet Tanager Holdings in Indiana. KFNF is now known as KYFR 920, and the KFNF call letters belong to an FM station in Kansas.

In 1963, the May family moved KMA out of the drafty Mayfair auditorium into a smaller, more modern radio facility across the street. The auditorium had become an expensive white elephant and it was finally demolished in 1966. KMA continues to operate as a successful regional broadcaster, with 5 kW station on 970 kHz and with a 100 kW FM sister station, KMA-FM.

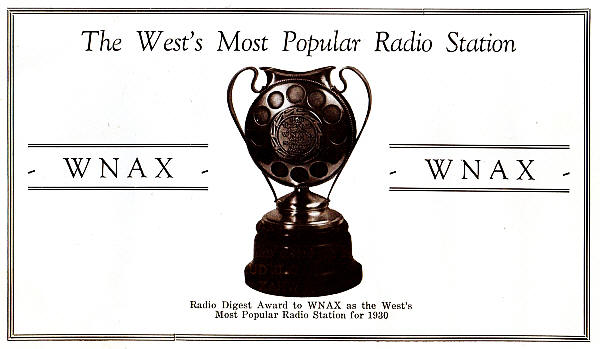

WNAX:

It’s said that the best form of flattery is imitation. If that’s true, then Field and May must have been flattered by the new radio activities taking place in neighboring South Dakota in 1927. The Gurney Seed & Nursery Company in Yankton, South Dakota was another important Midwest seed house in the early 1920s. Its owner, Deloss Butler “D. B.” Gurney, took note of the fact that his biggest competitors in Shenandoah were having great success because of their use of radio. His son, John Chandler ”Chan” Gurney, convinced him that he should buy WNAX, a defunct Yankton radio station license. After completing the $2,000 purchase, Gurney put WNAX back on the air from his personal residence on February 28, 1927, while new studios were being built on the third floor of the Gurney building. Two 60 foot towers were raised on the seed house property to support the antenna, and a homemade 1,000 Watt transmitter on the station’s favorable 570 kHz frequency gave WNAX a coverage radius of about 50 miles from 7:00 AM to 6:00 PM daily. The voices heard on WNAX included D.B. Gurney, George W. Gurney, “Chan” Gurney, Phil Gurney and Ed Gurney - it was clearly a family operation.

In addition to its seed and nursery business, the Gurney building featured a third floor mall housing a grocery store, barber shop, clothing store, jewelry store, restaurant, photo studio and a paint and hardware department. The new WNAX studio was located in this third floor mall, enclosed in glass and with seating for a large viewing audience. Another important Gurney business was their chain of 578 gasoline filling stations, operating in five states during the Depression. His WNAX “Fair Price” gas stations sold gasoline blended with corn alcohol (“Alky” gas) for as little as 17 cents a gallon - well below market prices and a welcome savings to cash-strapped farmers.

In 1936, WNAX built a modern showplace two-story transmitter building and tower five miles east of Yankton. WNAX continues to operate from this building today. In 1943 it added a new 927 ft. tower, which was the country’s tallest radio tower at the time. The tall tower, combined with its favorable 570 frequency and excellent ground conductivity, gave WNAX one of the best regional signals in the country.

In 1938, Chan Gurney ran for a seat in the U.S. Senate. He used the WNAX air waves to promote his campaign but denied equal time to his opponent. This resulted in a complaint to the F.C.C., who announced they were not inclined to renew the WNAX license under Gurney ownership. As a result, the station was sold in 1938 for $200,000 to the Des Moines Register and Tribune Company, the owner of three stations in Des Moines and Cedar Rapids, ending the Gurney family’s decade-long radio adventure.

Summary:

Radio as a business was a conundrum for many in the 1920s. On one hand, the public was enthralled with this latest form of home entertainment, and it clamored for more and better quality radio programs and stations. On the other hand, direct advertising was frowned on by both the public, and the government radio spectrum regulators made it clear that it would not be tolerated. So the universal question was, “How do you make money with radio?” The most frequent financial justification for early radio broadcasting was the establishment stations that served as indirect “goodwill” publicity vehicles for businesses. In the larger cities of this country, that meant radio stations became publicity organs for department stores, newspapers, hotels and automobile dealerships. But the small towns in the wide open spaces of rural America were also entitled to enjoy radio broadcasting, and different kinds of businesses were needed to support these rural stations. The mail-order seed and nursery houses of Shenandoah and elsewhere proved to be one successful solution that helped bring radio into millions of farm homes in the Midwest and Plains states during radio’s first decade.

PUBLISHED REFERENCES:

-

KMA Radio - The First 60 Years, by Robert Birkby, 1985

-

WNAX 570 Radio, 1922-2007, Arcadia Publishing Co., 2006

-

Booklet “Mayfair” by Earle E. May Seed & Nursery Co., 1928

-

Booklet “Behind the Mike with KMA”, 1926

-

“Iowa Journal of History and Politics”, 1944

-

Booklet “Studio and Broadcasting Station KFNF, The Friendly Farmer Station”

-

Souvenir and Picture Booklet of KFNF

-

Henry Arms Field biography by Sharon R. Becker

-

Booklet “WNAX the House of Gurney 1866-1929”

WEB REFERENCES:

-

http://www.victoryradio.com/station_histories/kfnf_shenandoah.html

-

http://tenwatts.blogspot.com/2010/11/seedlings-of-radio.html

NOTE: This article appeared in the Monitoring Times Magazine, December, 2012, entitled "The Rise of the Seed-Selling Radio Stations".

www.theradiohistorian.org

John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC

Copyright, 2012