The Newspaper

of the Air:

Early Experiments with Radio Facsimile

By John Schneider, W9FGH

www.theradiohistorian.org

Copyright 2011 -

John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC

(Click on photos to enlarge)

A 1938 publicity photo shows a home user of a Finch printer reading a facsimile newspaper broadcast over WWJ in Detroit. (Detroit News Archives)

So easy to use, even a child can operate it. A 1938 publicity photo shows a Finch home printer receiving a facsimile newspaper from WWJ in Detroit. (Detroit News Archives)

This 1938 photo shows a Finch home facsimile printer with the cabinet removed. . (Detroit News Archives)

William G. H. Finch, who developed a commercially viable radio facsimile system, and marketed it in the 1930s.

This article appeared in Popular Science Magazine in May of 1939.

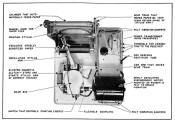

This diagram from an early Crosley brochure shows the inner workings of the Finch facsimile printer. A swinging arm moves back and forth in an arc, etching the image onto photosensitive paper.

Interior view of a Finch facsimile machine.

Another view of the Finch facsimile printer at WWJ (center). At left is a Crosley shortwave receiver. A Finch modulator is at right. (Detroit News Archives)

An engineer at W9XZY in St. Louis prepares an RCA scanner for the transmission of a news bulletin in 1938.

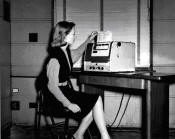

A St. Louis Post Dispatch employee reads the facsimile newspaper received over W9XZY. An RCA printer is shown. The black roller at the top contains the used carbon paper after the page has been printed. (Wide World Photo, 1938)

RCA engineer Charles J. Young examines a daily facsimile newspaper received in the RCA exhibit at the 1938 National Association of Broadcasters Convention in Washington, D.C. (Source unknown, probably an RCA publicity photo.)

This photo shows the 100 Watt ultra-shortwave transmitter that WHAS in Louisville used to transmit its daily facsimile news bulletins over its station W9XTW in 1939. (Scott Cason)

This 1946 photo from WENA, the Detroit News FM station, shows an improved post-war facsimile printer. With the greater bandwidth that FM offered, four 9x12 inch pages could be transmitted in a fifteen minute period. (Detroit News archives.)

INTRODUCTION

In the early 1930’s, radio was the newspaper’s worst enemy. Radio competed for advertising dollars and offered a free news alternative to a cost-conscious public during the depression years. It also offered an immediacy that was not possible for a newspaper, and which publishers feared could undermine their business. The result was a war waged by newspaper interests against radio in the 1930’s that attempted to keep stations from broadcasting the news. The wire services at first boycotted radio completely and later set up a Press Radio Bureau that was designed to give broadcasters limited amounts of news service with restrictions designed to keep radio from competing with newspapers. But some radio stations, particularly WOR in New York, revolted against this attempt by newspaper interests to monopolize news reporting and banded together to form their own news service, the Transradio News. Despite a host of legal challenges, Transradio survived and thrived, and eventually broke the newspapers’ monopoly on the news. The result was an about-face strategy by the newspapers — they began to buy up radio stations in major cities around the country under a “if you can’t beat them, join them”, philosophy. Soon there were stations owned by the major newspapers all over the country: in Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis, Sacramento, San Francisco and elsewhere.

The obvious next step was for newspaper owners to find a way to “synergize” their newspaper-radio combinations. One of the methods they tried was a new technology called Radio Facsimile.

Radio facsimile had the potential of becoming the “dream application” for newspaper-owned radio stations. In the short term, it would allow them to transmit news bulletins to their subscribers overnight via the airwaves, generating additional subscription and advertising revenue. It also had the long-term potential to eliminate the costly newspaper printing and delivery process completely, allowing the delivery of news to subscribers via radio at a relatively low cost. It could also shift the distribution cost from the publisher to the consumer if the latter could be convinced to purchase and maintain his own facsimile printer. These motives and other factors resulted in a flurry of experimental radio facsimile activity on radio stations around the United States in the latter part of the 1930’s.

EARLY RADIO FACSIMILE EFFORTS

The concept of sending images by wire had been around for a long time before it was ever applied to radio. The first rudimentary fax patent was issued in Paris in 1843 and used a swinging pendulum to draw the image. Englishman Edwin Belin first demonstrated his Belinograph in 1913. Western Union and AT&T both transmitted photos via wire in the early 1920’s, and the technology was quickly accepted by the press as a way to send newspaper photos instantly to cities around the country. RCA was the first company to adapt facsimile to radio, and sent a transoceanic image of President Calvin Coolidge from New York to London on November 29, 1924. Two years later, RCA began a commercial service of transmitting transoceanic photos by shortwave radio for the newspaper industry, and transmitting weather maps to ships at sea. RCA’s patented “Photoradio” technology was invented by RCA scientists Richard H. Ranger and Charles J. Young. It used a rotating drum and a photoelectric scanner to convert a document into a continuous tone that varied in pitch with changes in the image. The image was reproduced on the receiving end with another rotating drum having a stylus that pressed black carbon paper against white paper to reproduce the image.

A few radio broadcasters showed early interest in adapting the technology to send pictures to the public. KPO in San Francisco, owned by the San Francisco Chronicle, became the first radio broadcaster to transmit a photograph by radio when it transmitted a picture of cartoon character Andy Gump on August 22, 1925. The image was signed by Chronicle publisher George T. Cameron with the message "Radio's latest wonder - pictures through the air. What new marvels will this science bring forth?" The image was received on a single machine invented by C. Francis Jenkins. Some other early radio broadcasters who experimented with the transmission of images via AM broadcasting were KSD, owned by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, WTMJ, the Milwaukee Journal station, and WOR in Newark. In fact, KSD had conducted experiments with facsimile transmission over phone lines as early as 1923. WOR used the Cooley-Ray Foto System developed by Austin Cooley to transmit images late at night. Experimenters could make their own Cooley-Ray receivers by modifying old phonographs.

WILLIAM FINCH MARKETS THE RADIO FACSIMILE

But William G. H. Finch was the person who really brought radio facsimile into the public’s eye. Finch was born in England in 1897 and moved to Cincinnati in 1906, where he studied electrical engineering and radio communications at Columbia University and the University of Cincinnati before going to work for the Hearst Family’s International News Service. While at the INS, he set up the first radio teletype circuits between New York, Chicago and Havana.

While working for the INS, he developed an interest in facsimile machines, and his experiments led him to amass a portfolio of patents that eventually numbered in the hundreds. In 1935, he established his own company, Finch Telecommunications Laboratories, to build and market his system. Unlike RCA, who had only concentrated on the commercial applications of its technology, Finch envisioned the delivery of newspapers to the general public via radio facsimile. The Finch system got around the RCA patents in a number of ways. First, the image details were transmitted by varying the amplitude of an audio tone instead of its frequency. Secondly, it recreated the image by generating an electric current at the tip of a stylus that traced the image onto thermally sensitive paper. Synchronization between the transmitter and receiver was accomplished by using the 60 Hz line voltage frequency.

The Finch scanning head used a light bulb, lens and photocell to focus a pinpoint scanning spot on the document. An electric motor moved the scanning head across the page and another motor advanced the page slightly at the end of each scanning line. The voltage created by the photocell was used to vary the intensity of a high frequency tone, and low frequency sync pulses were inserted to signal the end of each line. The result was an audio signal that could be fed into any conventional AM transmitter.

The Finch receiver, which sold for $125, was housed in a one-foot square wooden box and could be connected to the speaker of any radio receiver having at least 3 Watts of audio output. The speaker needed to be turned off and the receiver volume adjusted to get the proper contrast on the page. The received images were drawn onto a continuous five inch wide strip of thermal paper. A roll of paper sold for one dollar and would last a week under normal use. An electric motor moved the writing stylus slowly back and forth across the paper, delivering an electric current that corresponded to the image. The current burned off the orange or white coating on the paper, allowing the black surface underneath to show through. Another motor advanced the paper slightly when it received a sync pulse, preparing the paper for the next scan line. (Finch was the first to use the thermal paper technology that was used in early FAX machines and continues to be used today for cash register receipts.) The transmission process was slow, requiring about 20 minutes to print one 12-inch page. However, the consumer could set up a timer on his receiver to capture the transmissions from a local AM station that broadcast the facsimile service during overnight hours when there were no normal radio broadcasts. Six hours overnight was enough time to print a six page two column news bulletin, delivered in time for breakfast.

THE FIRST FCC REGULATIONS OF RADIO FACSIMILE

The first experimental radio tests of the Finch system took place in 1933 over W10XDF, transmitting from the Teterboro Airport in New Jersey. By 1937, Finch had developed his technology into a practical radio facsimile system and he was able to convince several radio stations to begin regular use of the technology. The participating AM stations transmitted their radio newspapers overnight to a small number of Finch receivers in the homes of consumers who agreed to participate in the experiment. (Besides the transmission equipment, each station was required to purchase 50 receivers at $125 each.)

In September of 1937, the F.C.C. authorized the first radio stations to broadcast a facsimile service on an experimental basis, provided that no advertising or other revenues were generated. The first real broadcast of printed news via radio took place on October 15, 1937 over KSTP in St. Paul, Minnesota. WGH in Newport News, Virginia, and WHO in Des Moines, Iowa, also participated in the early testing. At the NAB Convention in Washington in February of 1938, the Finch technology was demonstrated to radios broadcasters by transmitting a daily convention news report prepared by the editors of Broadcasting Magazine. By March of that year, Mutual’s WOR in New York was also conducting experiments with the Finch equipment, and in April 2,000 amateur radio operators witnessed a demonstration of the WOR system at a hamfest in Newark, New Jersey.

W9XZY IN ST. LOUIS BROADCASTS THE FIRST REGULAR FACSIMILE NEWSPAPER

Meanwhile, RCA had become aware of the sudden success of the Finch system. They were the originators of radio facsimile technology but had never considered its usefulness in terms of transmission to the general public. Determined not to be left behind, they quickly repackaged their commercial system into a format more suitable for the public, and in 1937 they convinced the St. Louis Post-Dispatch to test it on their station KSD. While the initial transmissions were sent out overnight on KSD, by December of the following year they had moved it to W9XZY, an experimental ultra-high frequency station that was constructed with RCA’s help in St. Louis. Using 100 Watts on 31,600 kHz, the station had a range of about 20 miles. Daily transmissions of the radio newspaper using the RCA system began in February of 1939. There were several reasons to use a dedicated transmitter for facsimile. For one thing, the transmissions need not be limited to overnight hours and so the Post-Dispatch broadcasts were now being made daily at 2:00 PM. Secondly, the ultra-high frequencies were less susceptible to radio static, which greatly disrupted the received image quality.

RCA provided 15 receivers for the experiment, which were placed at Washington University and in homes around the St. Louis area. The receivers, offered to the public for $260 each, combined an ultra-high frequency receiver and facsimile printer into a single cabinet which had no controls or adjustments. The user simply kept the receiver supplied with rolls of carbon paper and white printing paper, which passed over the revolving metal cylinder containing the printing stylus. A metal bar moved with the printing signal’s intensity to vary the pressure on the stylus and create the image.

The W9XZY radio newspaper consisted of 9 pages, 8-1/2 inches long and four columns wide, and was printed in standard 7-point newspaper type. It featured news articles of the day, sports news, photographs, an editorial cartoon, a daily radio schedule, a radio gossip column and a page of financial news and stock market prices. It took about 2 hours to transmit a complete issue of the paper. Like the Finch system, it came out in a continuous strip that could be cut or folded for convenient reading.

OTHER STATIONS BEGIN FACSIMILE BROADCASTS

In October of 1937, the FCC gave permission to WGH in Newport News, Va., and WHO (AM) Des Moines, Iowa to experiment with facsimile broadcasts from midnight to 6 AM over their regular frequencies. Both stations would use the Finch system.

In 1938 in California, McClatchy Newspapers published the Radio Bee which was broadcast over its stations in KFBK in Sacramento and KMJ in Fresno. McClatchy had a staff of seven to produce the radio newspaper, mostly technicians, and bought 100 Finch receivers and distributed them to listeners in Central California. Unfortunately, the McClatchy service only lasted a year.

In 1938, Finch facsimile signals also began emanating from WGN in Chicago, WHK in Cleveland, WSM in Nashville and WWJ in Detroit (The Detroit News station). In 1939, W2XBF New York started regular service for three hours a day. Mutual Network stations WOR New York, WGN Chicago and WLW Cincinnati all began facsimile transmissions the same year using Finch equipment. In addition to creating their own local news content, the three stations traded material among themselves for use by all stations.

At first, stations worked with their newspaper owners or other local papers to provide the "radio printed" news. (The exceptions were WHO and WGN, who used Transradio News Service as their news source.) Transradio also announced plans to install 25 of its own stations around the country, with all news content prepared in New York. Transradio president Herbert Moore says the present newspaper “is four times too big and four times too expensive to operate.” (However, there is no indication that these stations were actually built.)

By 1939, nine AM stations were broadcasting a daily facsimile service: KFBK, Sacramento; KMJ, Fresno; WBEN, Buffalo; WGN, Chicago; WHK, Cleveland; WHO, Des Moines; WLW, Cincinnati; WOR, Newark, NJ; and WSM, Nashville. All stations transmitted their news bulletins between midnight and 6 AM.

Nonetheless, the preferred method of operation was increasingly shifting from overnight broadcasting on the AM band to the creation of dedicated shortwave and ultra shortwave facsimile stations. In 1938, the FCC had allocated 2012, 2016, 2096 kHz exclusively for facsimile broadcasting, but it rescinded the allocations the following year and replaced them with channels at 25, 43 and 116 MHz. In 1939, two thirds of the facsimile stations on the air were operating on the ultra high frequencies and the FCC received no new requests for overnight transmission on the AM band. Among the first of these stations to be assigned were two stations licensed to the Milwaukee Journal (the owners of WTMJ): W9XAF operated with 500 Watts on 41,000 kHz, and W9XAG had 1,000 Watts on 1614, 2398, 3492.5, 4797.5, 6425 and 8655 kHz In New York, Radio Pictures, Inc., had a 1,000 Watt license for W2XR (the predecessor of WQXR) permitting operations on 1614, 2012 and 2398 kHz, and from 86 to 400 MHz.

1939 saw a number of experimental stations authorized to operate on yet another group of frequencies: 38,600, 31,600, 35,600, 41,000 kHz The stations assigned to those channels included W8XTY, 150 Watts, The Detroit News (WWJ); W9XZY, 100 Watts, The St. Louis Post Dispatch (KSD); W8XE, Radio Air Service Corp (WHK) Cleveland, 50 Watts; W8XUF, Sparks-Withington Co., Jackson, Mich., 100 Watts; W9XSP, The Star Times Publishing Co., St. Louis; and W1XMX, The Yankee Network, Sargent’s Purchase, NH (Mt. Washington), 500 Watts. Also, the W.G.H. Finch Laboratories in New York had a “special experimental license” for W2XBF, which could operate with 1000 Watts on 38,600 and 41,000 kHz

That same year, RCA chose the occasion of the New York World’s Fair to promote its radio facsimile technology alongside its famous television demonstrations. It enlisted WOR to make daily transmissions using the RCA system, which were picked up for the public to see in the main hall of the RCA pavilion at the fair. WOR transmitted publicity pieces from a major motion picture studio on its 710 kHz frequency after 1:30 AM daily using its “Radioprint” system. (WOR also transmitted to the fair with the Finch system from 2 to 4 PM daily over its shortwave station W2XUP, 25,700 kHz, 100 Watts, its transmissions being received in the Crosley Pavilion.) RCA also cooperated with the New York Herald-Tribune to produce the “Radio Press”, an 8-1/2” x 12” newspaper that was only transmitted by wire within the confines of the RCA pavilion building. It used RCA’s new high-speed facsimile technology that could deliver a complete page every minute. RCA predicted that every home would soon have a facsimile receiver, and that advertising sales would cover all the costs of the service when it became authorized for commercial operation.

CROSLEY ENTERS THE FACSIMILE FIELD

At the 1939 Fair, RCA was promoting its home facsimile receiver for $260. But before the end of the fair, Crosley surprised everyone by announcing a new facsimile product called the “Reado”. There were two models that would sell for $60 and $80. A timer to turn the unit on and off over night cost an additional $10, and a kit version of the facsimile printer was available to experimenters at just $50.

Crosley’s 500,000 Watt station WLW in Cincinnati was one of the first experimenters with the Finch facsimile system, and its patriarch Powel Crosley Jr. had become fascinated with the business potential of the technology. Crosley was always a master at producing low-cost products (he was called the “Henry Ford of Radio”), and his low cost radio receivers in the 1920s had brought radio into millions of homes that could not have otherwise afforded them. Applying the same formula to radio facsimile, he licensed the Finch technology, made some improvements to lower the cost and started producing his own facsimile printer. He produced an initial stock of 500 units, and set up manufacturing in the factory to turn out up to 1,000 units a day.

A Crosley Reado brochure released in 1940 predicted a bright future for radio facsimile:

The art of transmitting pictures and other printed material by radio will advance. Nothing shall hamper its growth. Pictures of world events, cartoons, comic strips, news flashes weather maps, market reports, everything of a visual nature will soon be coming over the air. It is not anticipated that facsimile will directly compete with the newspapers. It will unquestionably be and continue to be a source of flash news rather than detailed mass printed material which can only be supplied by the newspapers and periodicals. Facsimile does not directly compete with sound broadcasting. On a separate channel, it will unquestionably be available as an augmenting service, providing a visual record of material other than music and sound being produced for your perusal whether you are present or absent.

WLW transmitted its facsimile news service in the early mornings up until the first year of World War II. The Reado newspapers were also read over the air every morning.

THE PUBLIC LACKS INTEREST

Despite all the promotion and hype, radio facsimile was a technology that the public never asked for and didn’t really care about. Facsimile printers were an expensive luxury for people at the tail end of the depression while newspapers were cheap and delivered to your doorstep every day. Neither could stations and publishers interest many advertisers in supporting the new medium, they preferred the familiarity and security of the traditional newspaper.

The technology was also not without its problems. One of those was static, which was more disruptive to facsimile than to sound broadcasting - a short burst of static could wipe out a page or more of text. Operation on the high frequencies was designed to solve this problem, as the high band was less susceptible to static interruption. It also allowed daytime operation and the signals had wider bandwidths that made faster transmission speeds possible. However, the tradeoff compared to high powered AM radio was the signal range, which was typically limited to a radius of 30 to 50 miles.

Also, the consumer of the 1930s was not prepared to have such a complicated appliance in the home. Paper jams or the failure to change a paper roll resulted in missed service. There were speaker switches, timers and volume controls to be set. And the consumers complained that the transmission was too slow and the paper size too small.

Then there was the problem of the two competing incompatible standards: RCA and Finch. Broadcasters and consumers were reluctant to invest in equipment for fear of choosing the wrong system. (Similar standard battles have hampered the development of other technologies in more recent years - consider the experience with AM Stereo, the VHS/Betamax battle and most recently, the HD DVD/Blue-Ray standards fight.)

Also, some newspaper interests were afraid of the new technology’s potential to upset the established order of their business. Would radio facsimile be an adjunct to the newspaper or did it have the potential of replacing the newspaper? Yes it could be delivered for a lower cost, but it offered less space for news and advertising. Would it open the door to new competitors? In theory, anyone could get into the radio newspaper business without the needed large investments in printing presses and delivery trucks that kept most people out of the newspaper business. Billions of dollars of machinery investments could become obsolete overnight. The unions predicted that 150,000 men would lose their jobs in newspaper print shops alone if radio facsimile replaced the newspaper.

Radio facsimile was also competing with other new technologies for the public’s attention. By 1940, there were already a number of FM stations on the air as well as the first few experimental television stations. Those technologies were much more exciting to the public than facsimile, and it ended up lost in the shuffle. As a result of these and other issues, many radio stations had already discontinuing their facsimile services by the end of 1940, and, with the start of World War II, anything that was left of the service had come to an unceremonious end. By 1943 there were only three facsimile stations still on the air in the country: W9XWT in Louisville, W8XUM in Columbus and W2XWE in Albany.

POST-WAR ACTIVITY

At the end of the war, there was an effort by some to revive the radio facsimile concept. William Finch still believed in facsimile as a mass medium. He proposed delivering the news directly to consumers over telephone lines as a subscription service, but could never get the idea off the ground. In 1947, he demonstrated a colored facsimile system that used colored pencils mounted on four different rotating drums to create an image. (The technology was featured in a Popular Science article in November, 1947.)

For a while there was renewed experimentation with radio facsimile on the early FM stations. The greater bandwidth of an FM signal allowed four pages of information to be transmitted in 15 minutes. WFIL-FM, which belonged to the Philadelphia Inquirer, sent out twelve pages of news each day. WQXR and WGHF in New York and WENA in Detroit also made regular facsimile news broadcasts. Major Edwin Armstrong, the inventor of wideband FM, demonstrated that facsimile could be transmitted over FM subcarriers. Tests of the method were conducted for a time by WIOD-FM in Miami, which was owned by the Cox Newspaper Group.

The FCC, meanwhile, was now classifying facsimile as a parallel technology to television — both involved the delivery of images by radio — and it regulated both technologies under the heading of “visual broadcast service”. In 1945, when the FCC moved all FM broadcasters to the new 88-108 MHz band, it reserved 88-92 MHz for noncommercial broadcasting and 106-108 MHz for radio facsimile. In 1948, the Commission held hearings on selecting a proposed standard for facsimile broadcasting and finally adopted rules and standards for facsimile transmission on the FM band. However, no new FM facsimile stations were ever built and the FCC eventually reassigned the 106-108 MHz sub-band to FM audio broadcasting.

In retrospect, it’s clear today that the FCC was about ten years behind the curve in its efforts to regulate and standardize radio facsimile. Television was now the darling technology, FM radio was relegated to a back seat position for many years, and radio facsimile just became one more technological dead end. William Finch’s company went into bankruptcy in 1952 and RCA eventually took over many of his patents. Finch died in Florida in 1990 at the age of 93.

Radio facsimile, of course, continued to exist as a specialized commercial technology, and is still used today for the transmission of weather maps by satellite. Xerox found success leasing its “Telecopier” machines to businesses in the 1970’s, which allowed them to send documents across the country or around the world over ordinary phone lines. Improved analog and digital versions led to the fax machine boom of the 80’s and 90’s.

Today it’s extremely rare to find an old 1930’s radio facsimile machine in the hands of collectors, as so few of them were actually made. Many of the surviving Crosley Reado machines were modified in the 1950s by ham radio operators who converted them to receive weather maps sent out by shortwave to ships at sea. The few collectors lucky enough to have one now are the owners of a curious and short-lived bit of radio history that is nearly forgotten today.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

The Golden Web — Erik Barnouw, 1968

“Rotarian Magazine” September, 1939 - “Now, Newspaper by Radio” by Silas Bent

Radio Annual — 1938 to 1943 issues.

Broadcasting Magazine, 4-15-38.

Broadcasting Magazine 10-12-81 - 50th Anniversary Issue

Radio-Craft, March 1939 – “First Daily Newspaper by Radio Facsimile”

Antique Radio Classified, 2007 - “Radio and Newspapers in the 1930s - Just the FAX, Ma'am" by Michael A. Banks

New York Times November 17, 1990 - Obituary: “William Finch, 93; Held Many Patents In Radio Technology”

The First Quarter Century of American Broadcasting — E.P.J. Shurick, 1946

Popular Science, November, 1947 — “World’s First Color Fax Machine”

Time Magazine, April 29, 1946: “Radio: Newspaper of the Air”

Time Magazine June 21, 1948: “Radio Turns On the News”

INTERNET RESOURCES:

History of Facsimile: http://www.hffax.de/history/index.html

The Crosley Reado Printer Converts Radio Waves Into

Text And Pictures On White Paper http://www.hffax.de/history/index.html

Wikipedia article: Radiofax

The FAX Newspaper — by John H. Lienhard, University of Houston.

NOTE: This article appeared in the Monitoring Times Magazine, February, 2011.

www.theradiohistorian.org

John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC

Copyright, 2011