|

www.theradiohistorian.org

Copyright 2011 - John F. Schneider

& Associates, LLC

[Return

to Home Page]

(Click

on photos to enlarge)

WDGY Happy Hollow Band

|

|

One

of the strangest episodes in American radio took place in 1941, when the major

players of the radio industry joined together and boycotted all music licensed

by the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP). In the process, it changed the face of

American popular music forever.

ASCAP

was created in 1914 by a group of songwriters led by Victor Herbert. It took for itself the task of enforcing the

1897 copyright law, which required that anyone performing music for profit have

the consent of the copyright owners. This was relatively easy in the days when all

music performance took place in theaters and other public venues - ASCAP simply

collected royalties from theater owners based on a percentage of their box

office sales. But the new radio industry

created a problem for them- there was no way to know the number of

listeners. This spawned two decades of

haggling between ASCAP and the radio industry.

Early broadcasters, led by Zenith president and pioneer Chicago

broadcaster Eugene F. MacDonald, formed the National Association of

Broadcasters (NAB) in 1925 specifically to deal with the music licensing problem. In 1932, ASCAP set a blanket annual fee of 5%

of a station's advertising revenue. While

burdensome on the radio industry, which continually fought for better terms,

this became the recognized formula throughout the 1930s.

Everything

fell apart in 1940 when ASCAP announced it would triple its music fees for

radio at the end of the year. Broadcasters

vehemently opposed this, arguing that the exposure the music industry received via

the radio helped popularize new music and boosted sales, but ASCAP refused to

back down. An impasse had been reached,

and drastic action was needed.

In

September of that year, industry leaders met at the NAB convention in San

Francisco and decided on a drastic move that was designed to demonstrate the

influence of radio on popular music --beginning on January 1, 1941, most radio

stations and all the networks would boycott ASCAP music. That meant that, virtually overnight, more

than 1 million ASCAP tunes disappeared from America’s airwaves.

In

1939, broadcasters and the NAB had established BMI (Broadcast Music,

Incorporated) as the radio industry's own music licensing agency. $1.5 million had been set aside to create new

music compositions for broadcasting. BMI

actively sought out new composers who weren't already contracted to ASCAP and

released their music to stations at a much more favorable rate. These were mostly third-rate tunes penned by

unknown composers. When the boycott

happened, there wasn’t enough BMI music to meet the need.

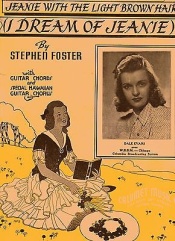

To

fill their airwaves, broadcasters turned to other sources of music. They

played songs from the public domain, such as familiar melodies derived from

classical works, and old American standards like "I Dream of Jeanne with

the Light Brown Hair". (Time

Magazine said that song was played so much that Jeanne's hair had turned

grey.) And they performed foreign music

that wasn’t licensed by ASCAP, especially Latin American standards like

"Perfidia" and "The Breeze and I". Still another source of new music were the

"hillbilly" and "race" tunes that ASCAP considered beneath

its dignity to license.

Radio’s

ASCAP boycott had far-reaching implications.

Most radio programs in the forties had opening theme songs, and many of

these were controlled by ASCAP. This

meant that Jack Benny couldn't play "Love in Bloom" on his violin,

and George Burns and Gracie Allen couldn't use their theme "Love

Nest", which had been written by ASCAP co-founder George M. Cohan. Instead,

substitute theme songs were found. (Some

astute program producers had avoided the problem completely by choosing public

domain theme songs, such as the Lone Ranger’s “William Tell Overture”, and the

Green Hornet’s “Flight of the Bumblebee”.)

The boycott also impacted the record industry, because recording artists

knew their releases of ASCAP tunes couldn't be heard on the radio. Some popular band leaders responded by

recording swing versions of public domain songs, such as Glenn Miller's

"American Patrol" and "Song of the Volga Boatmen".

Coinciding

with the start of the radio boycott, the Department of Justice began

investigating all the parties – ASCAP, BMI, and the networks - for possible

criminal monopolistic practices. This was

quickly resolved in February when ASCAP voluntarily signed a consent decree,

agreeing to offer broadcasters both blanket and per-piece licenses. However, several more months of negotiations

went by before all parties could agree on the rates to be charged. By the end of summer, ASCAP had signed an

agreement with NBC for 2.75% of net time sales on network broadcasts and 2.25%

for local station programs - less than half of what it had been getting before

1940.

The

ASCAP boycott officially ended in October of 1941 and America's popular music

returned to the airwaves. But something

had changed in those ten short months -- American listeners had been exposed to

new music genres that hadn't been heard previously, and they liked what they

heard. "Hillbillly" music quickly

morphed into the more refined "Western" music which became immensely

popular on radio throughout the forties, eventually leading to today's Country

music. "Race" music became

Rhythm and Blues, which then merged with jazz to become "Rock and

Roll". Latin rhythms and dances

like the Rumba and the Mambo became national sensations. In short, radio had demonstrated its tremendous

ability to shape popular music tastes.

Unfortunately,

with time broadcasters lost control of their own creation, BMI, and it today it

has become a functional clone of ASCAP. Once

again, the radio industry is battling with the music industry - this time over

performance royalties. In radio’s golden

era, most broadcast music was performed live, and so the artists were paid for

each performance. In fact, the American

Federation of Musicians exercised its own substantial power to keep most recorded

music off the airwaves. Of course, radio

today is the complete opposite, with almost no live music being heard on the

air. And so the debate rages as to

whether radio should now pay performance royalties, and the industry still

argues that its influence over popular music creates a symbiotic relationship

that merits special consideration. With

today’s greater diversity of music delivery methods, some people wonder if a

radio music boycott could ever have the same impact today as it did in 1941.

Copyright John F. Schneider, 2015. All rights reserved.

NOTE: This article originally appeared in Radio World Magazine, May, 2015

|