Disruptive Technologies that Changed the Course of

RCA's "Radio Central"

By John F. Schneider, 2022

|

|

Disruptive Technologies that Changed the Course of By John F. Schneider, 2022

|

|

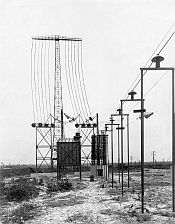

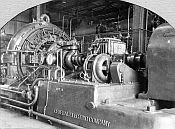

www.theradiohistorian.org Copyright 2022 - John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC (Click on photos to enlarge) A postcard view of RCA Radio Central at Rocky Point. A view of

the energy power station at RCA Radio Central. Power for the Rocky Point facility was provided by the Long

Island Lighting Company: 23,000 volts, three phase 60 cycle current to a

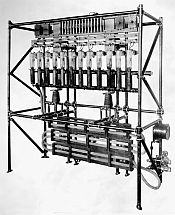

substation on the property. (Library of Congress)    Duplicate station built by RCA at Grimeton, Sweden. (Author’s collection)  One of two alternators installed at Grimeton. (Author’s collection)  The power control panel at Grimeton. (Author’s collection)  General Electric power vacuum tubes available in 1924: UV-206. 1 kW(left); UV-208, 5 kW(center); UV-207, 20 kW water-cooled tube (right). (Museum of Science and Innovation photo)

|

|

It was the

world’s largest radio station. It was

said in 1922 that RCA’s “Radio Central” at Rocky Point, Long Island, NY, was

the only station that could be heard anywhere in the world at any time, day or

night. At its

inception, RCA’s eventual future as a manufacturing and broadcasting giant was

not yet envisioned. Its primary function

was international wireless communications – the transmission of commercial

messages in the form of RCA “Radiograms”.

Even though RCA assumed operational control of American Marconi’s

existing wireless facilities in the U.S., it immediately made plans to build

the world’s most elaborate wireless facility.

Just a year after RCA’s formation, the company purchased a 5,100-acre

(26 square mile) tract of land at Rocky Point, Long Island. The rural area was free of electrical

interference and faced a clear path towards Europe. On that

property, RCA erected two massive flat-top antennas. Each one extended 7,500

feet to the east, and consisted of 12 parallel wires supported by six 410-foot

towers. Huge loading coils at the base

of each tower could be adjusted to tune a range of frequencies. An elaborate buried counterpoise system

compensated for Long Island’s poor ground conductivity. The first

two 200 kW alternators that had originally been built for American Marconi were

installed in Radio Central’s imposing new transmitter structure. A large water pond with eight fountain jets in

front of the building served as a cooling system for the alternators. Although there were initially just two

alternators and antennas, RCA planned to construct ten more pairs, with their

antennas arranged like spokes in a wheel radiating in all directions from the

transmitter house. That planned

alternator order was budgeted at $1.3 million ($21 million in today’s dollars). In

addition to this enormous transmitter property, another 2,000-acre parcel was

acquired at Riverhead, twelve miles southeast of Rocky Point. This became Radio Central’s receiving station. It was managed by Dr. Harold W. Beverage, who

constructed a nine-mile version of his highly-directional namesake antenna,

directed towards Europe. Initially this

antenna fed four “barrage” receivers with heterodyne detectors, also designed

by Dr. Beverage; future plans provided for another six receivers. RCA

inaugurated commercial traffic from “Radio Central” on November 5, 1921, when

President Harding pressed a celebratory key at the White House. The call signs were WQK on 18.3 kHz, and WQL

on 17.15 kHz. All Morse Code traffic

was managed from RCA’s headquarter building at 64 Broad Street in New York City

and sent to Rocky Point over telegraph lines.

The messages were punched onto paper tape and transmitted at 100-200 words

per minute. The received messages came

back to New York via telephone lines from Riverhead, where they were written to

inker recorders. THE

VACUUM TUBE AS A DISRUPTIVE TECHNOLOGY Concurrent

with Alexanderson’s work on the alternator, another team at General Electric’s research

laboratory had been experimenting with the original de Forest Audion receiving

tube. They initially found it to be

unstable and quirky in its operation, but thanks to efforts by Dr. Irving Langmuir

and his team of scientists, substantial improvements were made. A higher vacuum and the de-gassing of all internal

metal components permitted its operation at higher voltages, which achieved

greater stability and operating life.

Originally envisioned simply as a detector, the Audion’s usefulness was soon

expanded to include oscillation and amplification, and the addition of a second

grid further expanded its capabilities and performance. It wasn’t

long before larger and more powerful tubes followed, capable of radio transmission. G.E.’s primary customers during World War I

were the U.S. Navy and Signal Corps, but transmitter tubes were also being sold

to the United Fruit Co., amateur radio operators, and commercial ship-to-shore operators. Unfortunately, there were practical limits as

to how many tubes could be connected in parallel, and so the pressure to create

more powerful tubes was always present. Five

kW tubes like the UV-208 were determined to be the upper limit for air-cooled

glass tubes. This led to the development

of water-cooled tubes, whose copper anodes were immersed in sealed chambers filled with running

water. After considerable effort, the

obstacle of making an air-tight seal between copper and glass was

overcome. The successful result of this

project was the 20 kW UV-207 power tube, which would be manufactured in large

quantities and in various configurations through the 1940s. They would be built by both GE and

Westinghouse and sold by RCA for use in radio transmitters around the world. In 1921, RCA

had elected to use Alexanderson alternators at its Radio Central project

because vacuum tubes had not existed at sufficient power levels to achieve the

needed power outputs. But this had

changed with the new UV-207. Now, both RCA

and General Electric were eager to conduct a test to compare the Alexanderson

alternator with a high-powered tube transmitter. Accordingly, such a transmitter was built and

shipped to Rocky Point in 1922. It used

six UV-207 tubes operating in parallel and three rectifier tubes (which were really

just UV-207’s without grids). Its output

was over 100 kW on 18.3 kc., the same frequency used by RCA’s alternators. RCA provided free floor space and electrical

power for the experiments, and a crack team of G.E. engineers arrived at Rocky Point in May, 1922. Simultaneously,

AT&T was doing a test of single sideband voice transmitters at Rocky Point,

which it hoped to use for trans-Atlantic telephone service. 1 The two companies needed to share the use of

one of the large antennas, and so their work could not be done at the same

time. Because most of the experimental

work was done overnight, it took six months for G.E. to complete its

testing. There developed a friendly

competition between the two groups of engineers as to which one could get a

signal on the air first. But G.E. had

several troubling issues with its transmitter – parasitic oscillations,

frequency stability, antenna coupling, and Morse keying. Finally, its engineers elected to use one of

the alternators operating in low power as an exciter to drive the tube

amplifier. In November, 1922, after

sixteen hours of traffic was exchanged with Nauen, Germany, and another 10

hours with Caernavon, Wales, the project was declared a success. Impressively, neither the operators in Europe

nor New York could tell the difference between the alternator and tube

transmitter signals. The result

of this test was that RCA canceled its standing order for more alternators, and

replaced it with a quantity of less-expensive and more efficient tube

transmitters. From that date forward,

General Electric built no more Alexanderson alternators. The original units were eventually relegated

to standby service, although they remained in place and functional until

1947. RCA engineer Marshall Etter later

commented in an interview that “It was a good thing they didn’t build the rest because

… the whole thing would have been obsolete and RCA would have been in serious

financial trouble.” THE

SECOND DISRUPTIVE TECHNOLOGY - SHORTWAVES The shortwave

frequencies were already known when RCA built Radio Central. Frank Conrad at Westinghouse had conducted

test transmissions on 100 meters. He found

that he got good reception at night but poor conditions in the daytime. Then in December, 1921, a signal from amateur

station 1BCG in Greenwich, Connecticut, reached Ardrossan, Scotland, marking

the first successful trans-Atlantic radio transmission on the shortwave

frequencies. After that, amateur

stations continued to demonstrate long-distance communication at powers below 1

kW. Nonetheless,

the generally accepted theory at the time was that the shorter the wave, the

more losses. That is why radio amateurs had

been confined to below 200 meters –frequencies thought to be useless for

reliable communication. RCA had even acknowledged

that, while the short waves had an advantage for distances less than 3,000

miles because of their low atmospheric “absorption, the wavelengths over 11,000

meters provided the greater reliability for longer distances. That was why the decision had been made to

use alternators as the new company’s transmitters. But for

his part, inventor Guglielmo Marconi was skeptical, and he never accepted the

prevailing attitudes about shortwave. As

Dr. Clarence Beverage explained in an interview decades later: So, he built his station at Poldhu in Cornwall.

He started off transmitting around 100 meters. Then he tried 80 meters. He kept

coming on down, until finally in October 1924 he got down to 32 meters. The

whole world was astonished in that the signal got through, almost all over the

world, twenty-four hours a day. The fact that it got through in the daylight

was contrary to all theory. Here was an economical way of getting international

communication for the first time because the long waves required tremendous

antennas and very high power, and the number of frequencies available were very

small because there was only maybe 10,000 cycles that were useful out of

perhaps 40,000 cycles for all purposes. So,

the shortwave revolution, as you might call it, really changed the whole

picture of international communications. The whole world began to develop short

waves. By the

mid-twenties, G.E. had solved high frequency oscillation problems in the UV-207,

allowing it to operate up to 20 MHz. With

that development, RCA’s Clarence Hansell decided to conduct further tests, and

he built the highest-frequency transmitter that had ever been built to that

time with any appreciable power.

Beverage explained: The thing was rather amazing because it worked

on 15 meters, and the antenna was about a half a wavelength long, which would

be 25 feet. It was literally held up by

broomsticks, and the condensers were literally metal pie plates. It really was a remarkable thing. That transmitter was received extremely well

in South America. This was right under

the big antenna, which was a mile and a quarter long, 410 feet high with a

cross arm on it. Rocky Point with its 200 kW … could not break through the heavy static down there in South

America, but here was this little 15-meter transmitter banging along just fine.

It probably cost 1, 2 or 3% of what the

big antenna did. By 1927,

RCA revealed that it had been operating a 15-meter link to Buenos Aires for a

year, using the call sign 2XS. The

two-tube transmitter delivered 7 kW into a horizontal doublet with a reflector

at 20 feet elevation. Its signals were

being received in Argentina daily without fail from 6 AM to early evening. From that

point forward, RCA gradually installed several dozen shortwave transmitters at

Rocky Point. They ranged in power from

10 to 40 kw, and fed Rhombic antennas directed towards Europe and South

America. By the mid-30’s, a total of eighty

call signs were being used. A 200-kW

shortwave transmitter went into service in November of 1935. Although longwave stations continued to

operate at Rocky Point and several other locations around the world, the

majority of international messaging was now being done on the shortwave bands. POST

SCRIPT Change is inevitable. Today we know that other disruptive technologies eventually came along, which made both the vacuum tube and shortwave communications obsolete. After satellite communications became the norm in the 1970’s, Radio Central was dismantled and the land was sold to New York State for one dollar. It is now a public park, known as the Rocky Point Pine Barrens State Forest, and nothing remains of its former life as a communications icon. Today there remains only one

Alexandersson alternator, the others having been scrapped more than

sixty years ago. The original RCA-built longwave station at

Grimeton, Sweden, is maintained today an historic site. It is the

only station left in the transatlantic network of nine long wave

stations that were built during the years 1918–1924. During World

War II was Sweden's only telecommunication link with the rest of the

world. The Alexandersson alternator has been maintained in operating

condition, and it is fired up each year on Alexandersson Day, July 3,

broadcasting Morse code messages to the world with the call sign SAQ. We know

that science today moves even more rapidly than it did in the 1920’s, and that

promising new technologies can reach obsolescence within a few years instead of

decades. Indeed, many of industry’s

leading technology companies of the past are now only memories – including RCA

itself. And therein lies the lesson of

Radio Central for today’s technology companies:

always leave a door open for the surprise appearance of disruptive

technologies.

1 This service operated at 57 kHz

between Radio Central and New South Gate, UK.

The first public demonstration was January 1923, although commercial

operation did not begin until 1927.

This article

originally appeared in the December, 2022, issue of The Spectrum Monitor Magazine REFERENCES:

|