The Pacific Coast Biscuit Company was a competitor to KOMO's owner, the Fisher Flouring Mills, and had several mills located around the West. The owner of the Pacific Coast Biscuit Company, Moritz M. Thomsen, felt he had to match his competitor’s radio efforts, and so he started the Queen City Broadcasting Company. His station, KPCB, went on the air April 1, 1927 from a tiny studio in the Central Building, and with a 50-watt transmitter in the Pacific Biscuit Building at 4100 East Marginal Way. KPCB increased its power to 100 watts later that year, sharing a frequency with KPQ until that station moved to Wenatchee. The KPCB transmitter later moved to the roof of the Rhodes Building when KOL vacated its antenna there.

Unlike the Fishers, Thompsen never spent the money to turn KPCB into a serious station, and it was the butt of local jokes for its lack of money to buy equipment or replacement parts. For example, during remote broadcasts the station’s only microphone would be rushed to the remote location by taxi while phonograph records were played to cover the air time.

In 1935, Moritz Thompsen’s son had a legal run-in with Saul Haas, the director of the U.S. Customs Office in Seattle and a former Democratic Party campaign organizer. Haas received 700 shares of KPCB stock as a settlement, which sparked his interest in the radio business. Soon, he led a group of businessmen to purchase the remaining shares and changed the call letters to KIRO.

The next year, flexing his political muscles, Haas gained approval to increased KIRO’s power to 1,000 watts and move to 710 kHz, a frequency it did not have to share. He also lured the lucrative CBS network affiliation away from KVI and KOL. And in 1941, he obtained approval to increase KIRO’s power to 50 kW, creating the Northwest’s first maximum-power station.

During the 1940s, KIRO and CBS were the Puget Sound Region’s major source of important war news. Haas instructed his staff to make daily recordings of all CBS news broadcasts for delayed rebroadcast. This collection of KIRO acetate disks, now in the National Archives, is the largest collection of war news recordings extant today.

(From the book "Seattle Radio" by John Schneider, 2013.

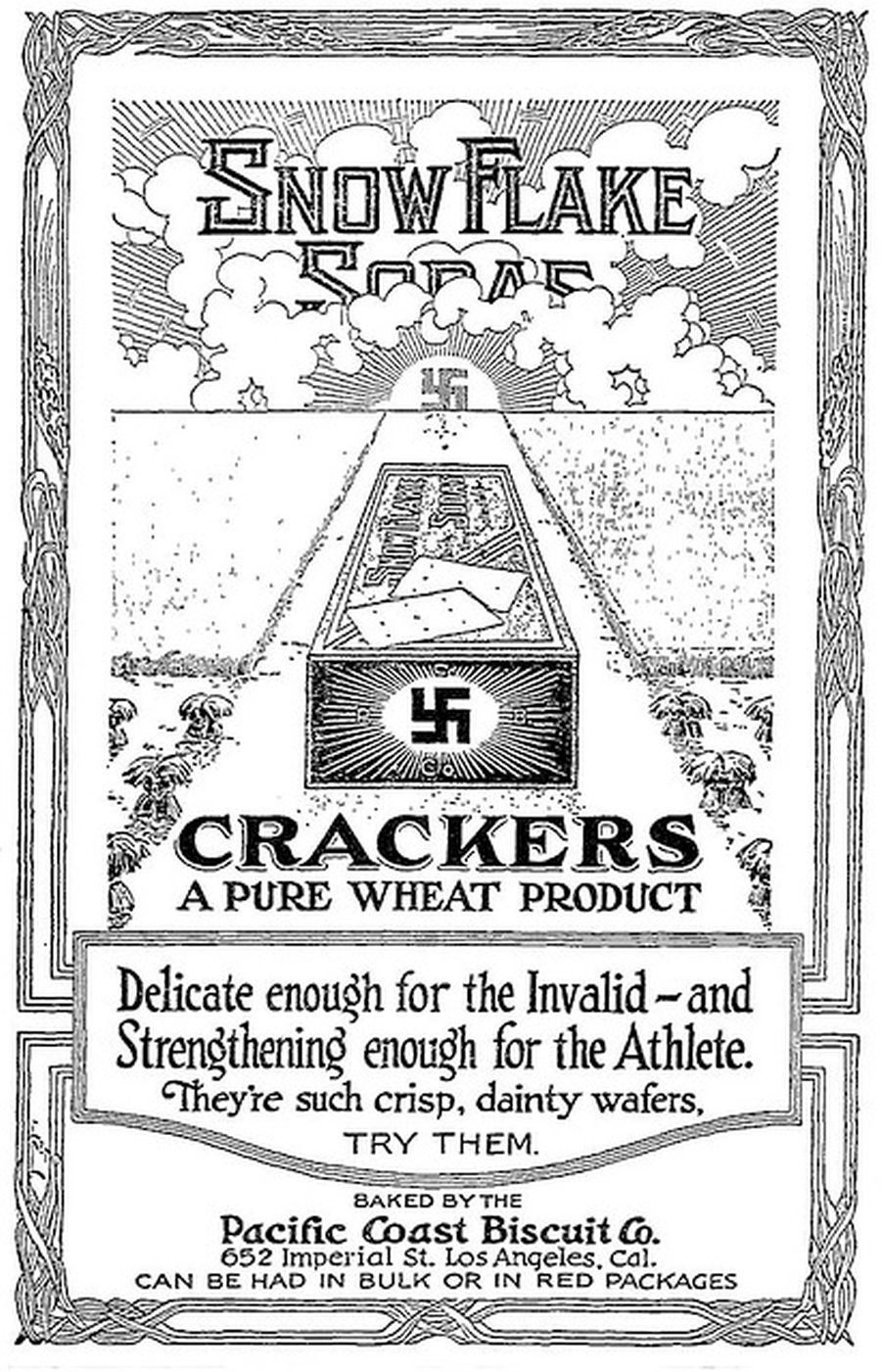

This newspaper article from April 1, 1927, described the inauguration of the Pacific Biscuit Company's station KPCB in Seattle.

The Pacific Coast Biscuit Company was a competitor to Fisher Flouring Mills, with several locations around the West. The company’s unfortunate choice of trademark was a swastika, which was quickly changed at the start of World War II.

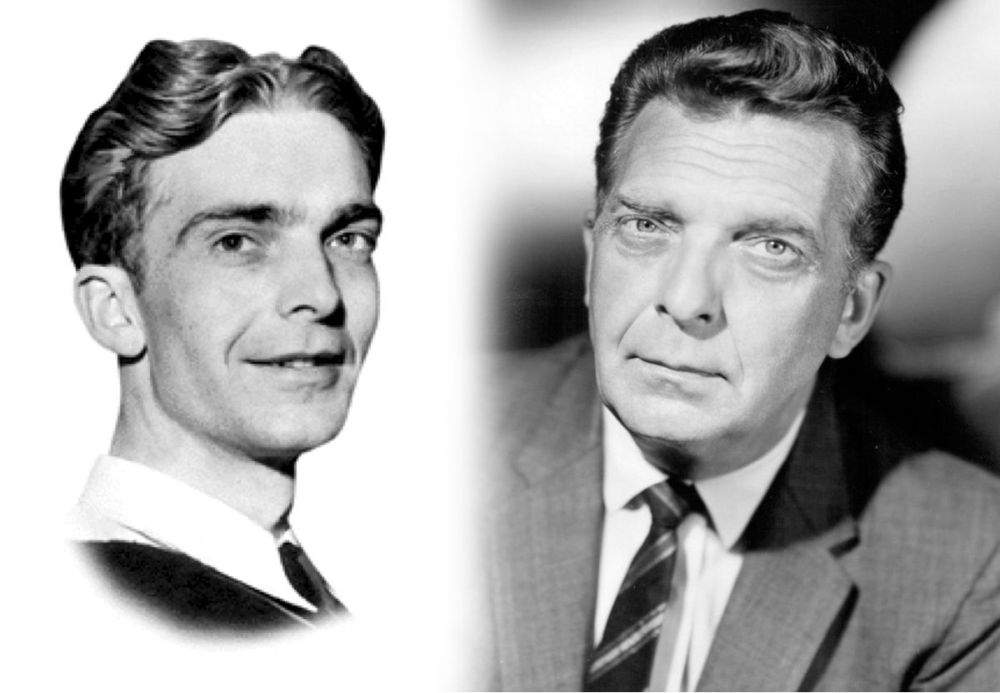

Revered NBC news anchorman Chet Huntley started his career at KPCB in Seattle. The 24-year-old University of Washington student walked into the first radio station he could find and applied for a job. In a few minutes, Huntley was the new KPCB program director. "I ran sort of an underground news broadcast - I bought the newspaper from the corner and rewrote it", he later said. "I also ran the transmitter, spun records, wrote ad copy and swept out."

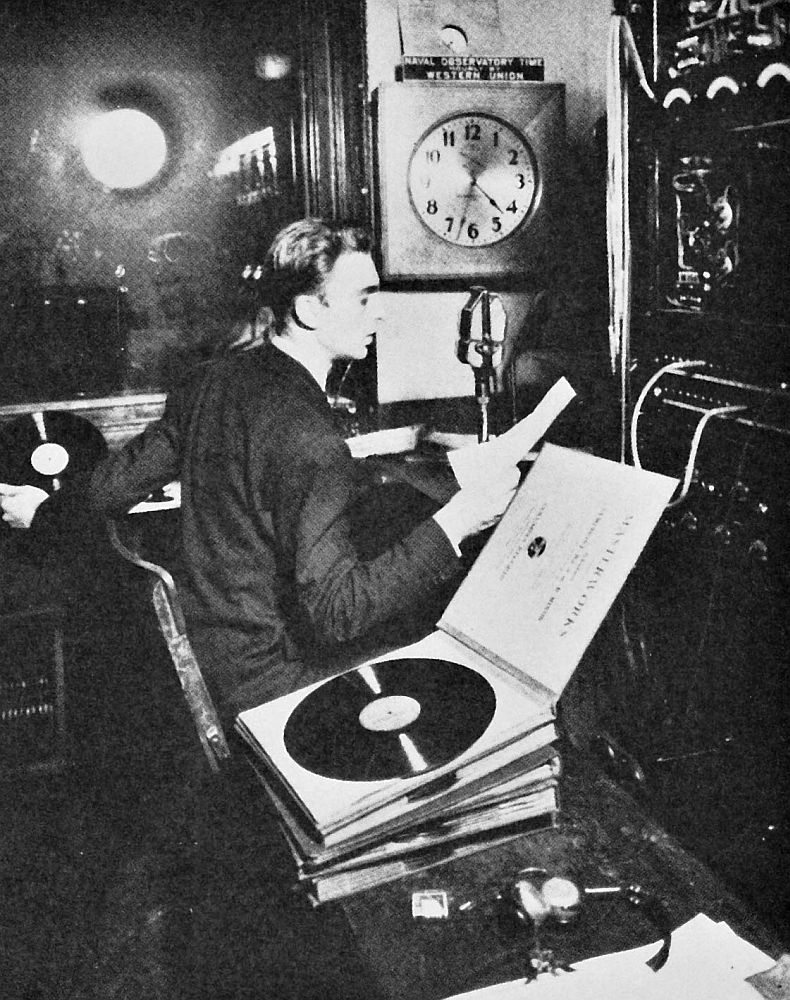

This was Chet Huntley on the air at KPCB in 1934. He is producing an opera program using phonograph records of music and sound effects, and adding his own commentary.

Saul Haas enjoyed many political connections. He joined with several Seattle businessmen to purchase KPCB in 1935. On October 15, U.S. Vice President Garner and other dignitaries attended a ceremony boosting power from 250 to 500 watts. The same day, KPCB’s call letters were changed to KIRO, now operating from new studios in the Cobb Building.

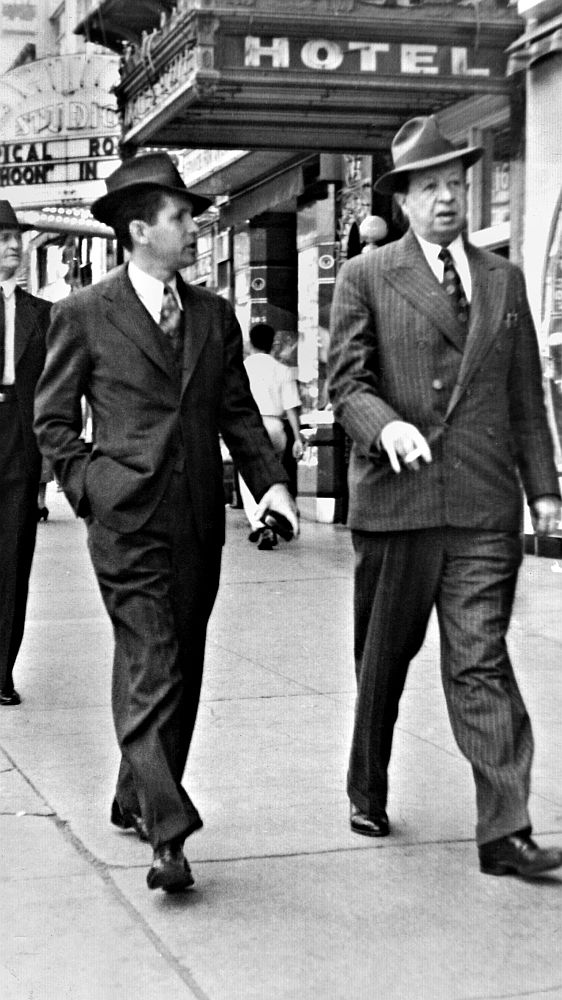

Saul Haas' ample political influence was put to use in convincing the FCC to gain higher power and a better frequency. Engineer James B. Hatfield, seen here with Haas, was Haas' technical guru. Together, they turned KIRO into the most powerful and influential station in the Northwest. (Jim Hatfield photo)

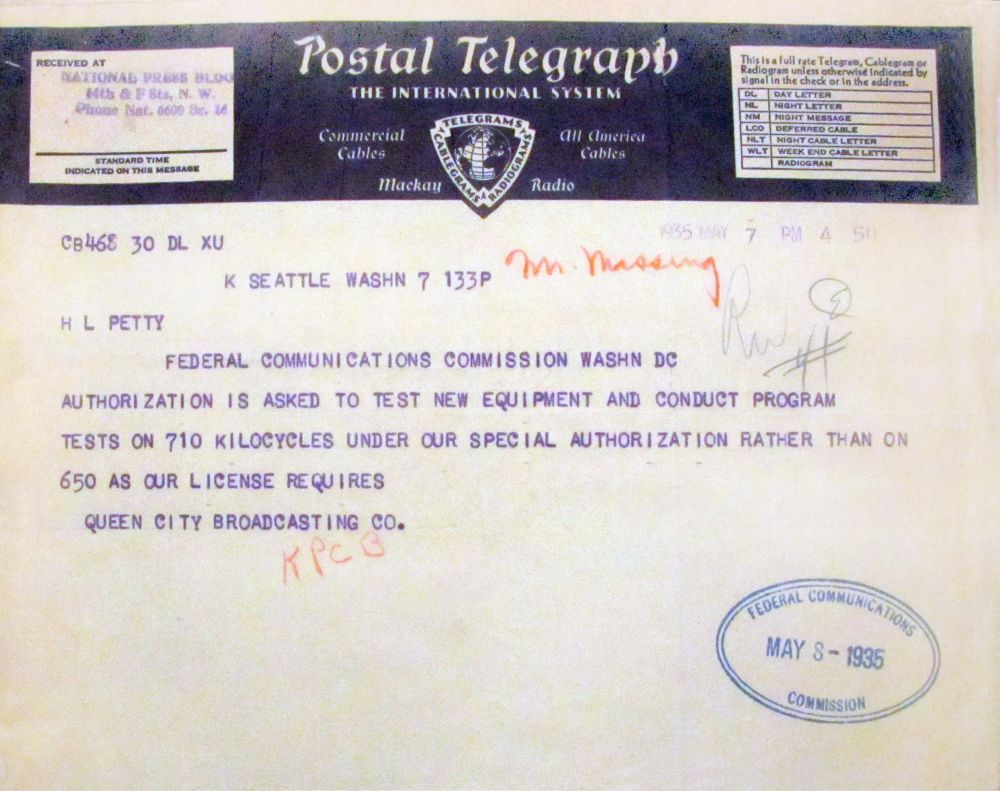

KPCB could only operate during the daytime to protect a Nashville station on 650 kHz. But Haas’ influence helped him achieve a change of frequency for KIRO to 710 kHz with unlimited hours. A formal move to the new channel wasn’t allowed, but Homer Bone convinced the FCC to permit KIRO to operate on an “experimental” authorization, which was renewed every three months for the next four years. (National Archives)

The KIRO transmitter, now operating on 710 kHz, moved in 1936 to the top floor of the Rhodes Department Store, using a rooftop antenna that had recently been vacated by KOL. In 1937, Haas and Hatfield petitioned the FCC to increase power to 1,000 watts. This map that KIRO submitted to the FCC shows the station's projected 100 mV "blanketing" coverage.

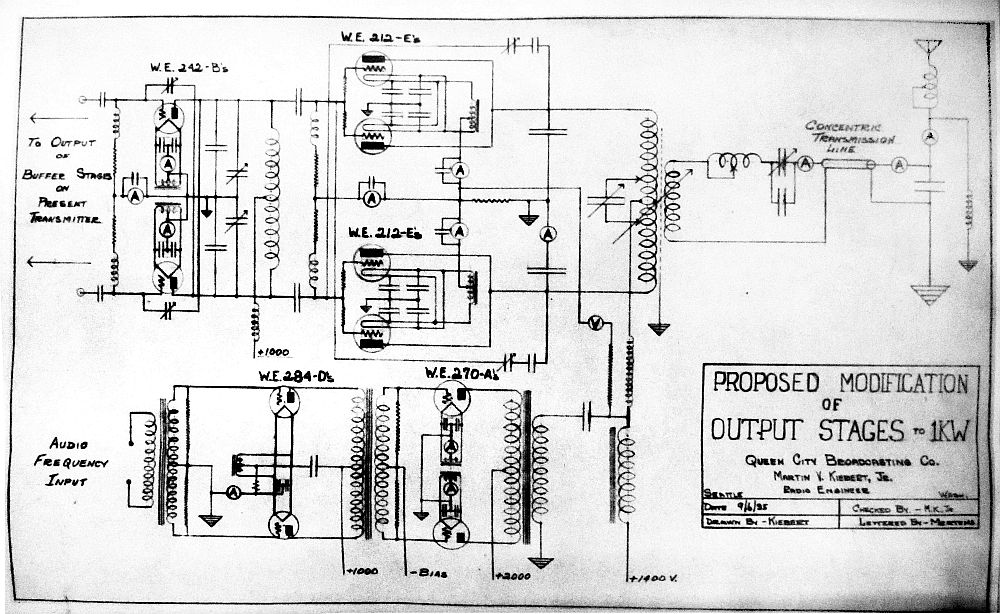

This circuit diagram was filed with the FCC. It describes the new 1,000 watt power amplifier that KIRO built for its power increase. It used a low-level signal from the original transmitter and amplified it to 1,000 watts.

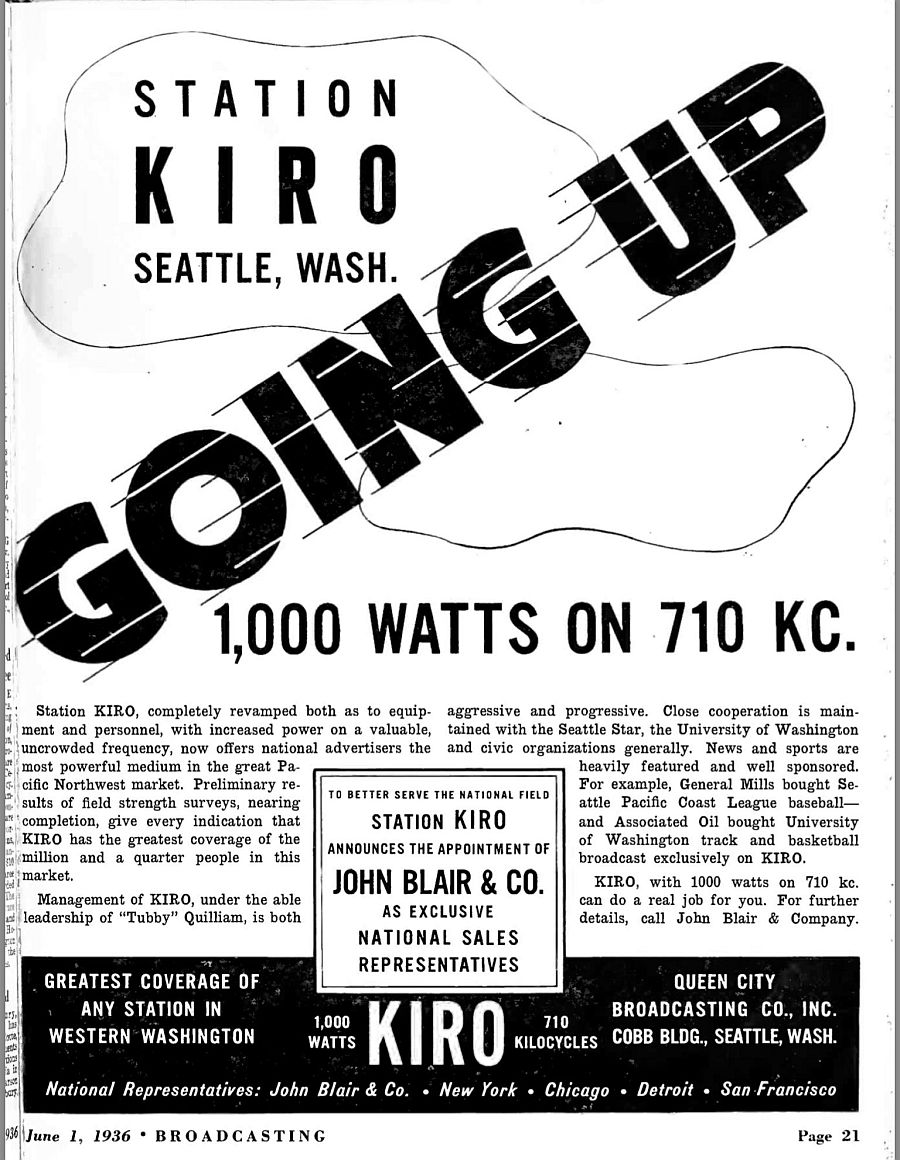

After successfully increasing KIRO's power to 1,000 watts, Haas ran this ad in "Broadcasting", the radio industry's most influential trade magazine.

The University of Washington rowing team was big news in the 1930's. The team dominated the Pacific Coast, and in 1936 won a Gold Medal in the Berlin Olympics (as told in the movie "Boys in the Boat"). After that, the team's local following was so high that KIRO would broadcast the local races. The announcers here are on the air live via a shortwave link from the ship canal. (Jim Hatfield photo)

One of KIRO's popular programs in 1940 was "Gold Shield Coffee Time", 30 minutes of live music on Sunday nights. The KIRO Gold Shield orchestra was conducted by the Cuban violinist and recording artist Max Dolin, who had had a long and successful radio career on the Pacific Coast. He had previously been the music director for NBC's West Coast network.

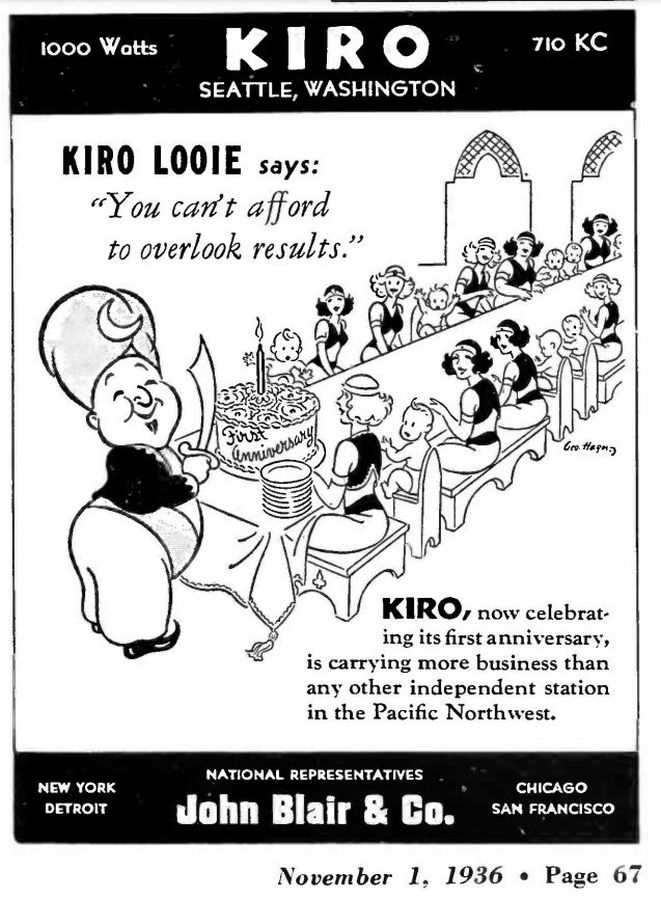

KIRO called itself "The Friendly Station" in the 1930's. It's on-air announcers used a more conversational, informal style, which was different than the stilted, formal sound of early radio. "Kiro Looie" was the station mascot, and was featured in many ads and promotions.

Orchestra leader Wally Anderson was another KIRO musical favorite. His programs were broadcast live from the Georgian Room of Seattle's Olympic Hotel during a three-year engagement.

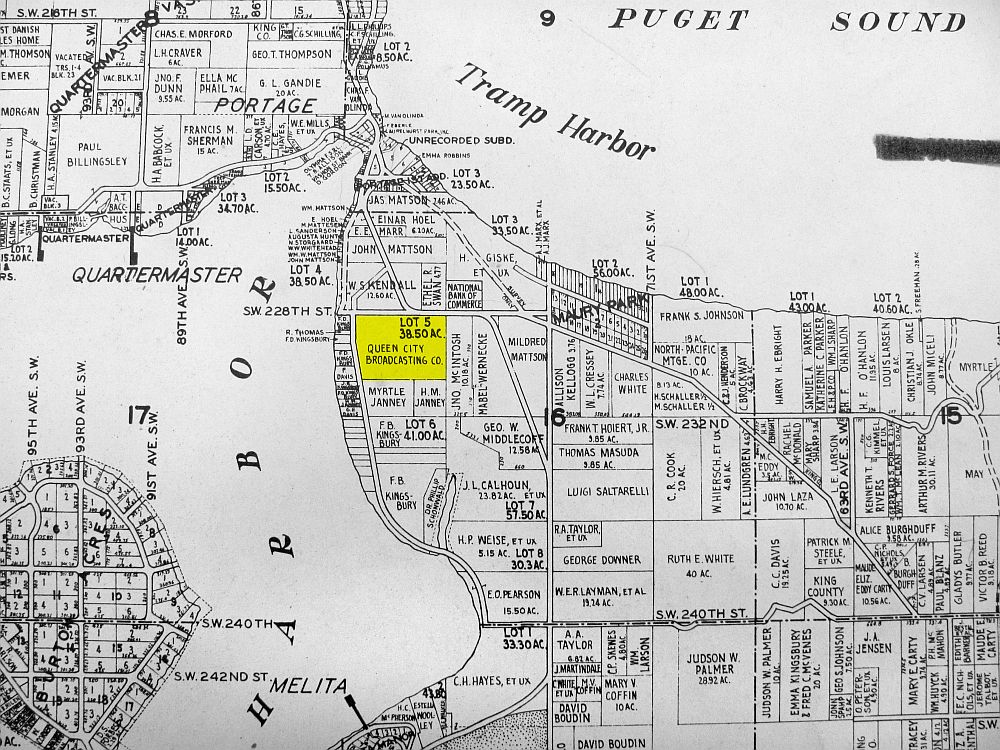

KIRO's experimental use of the 710 frequency ended in 1939, when the FCC gave both WOR in New York and KIRO in Seattle official "Class 1-B" status. This cleared the way for KIRO to ask for another power increase, to 10,000 watts - later upgraded to 50,000 watts using a directional antenna. Haas acquired property for a new tower site on Maury Island, giving KIRO a powerful signal into both Seattle and Tacoma.

The 37-acre Maury Island property was purchased at a cost $5,821. It had been clear-cut 30 years before, but 600 old-growth stumps remained and had to be removed by blasting. It took a road-building crew nearly 4 months to finish the job. (Jim Hatfield photo)

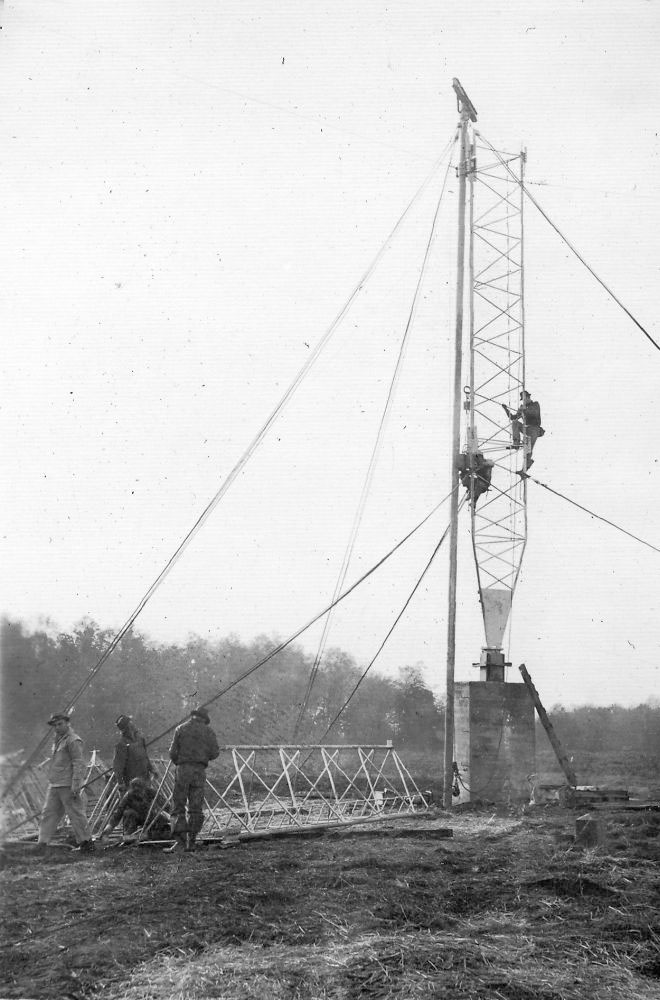

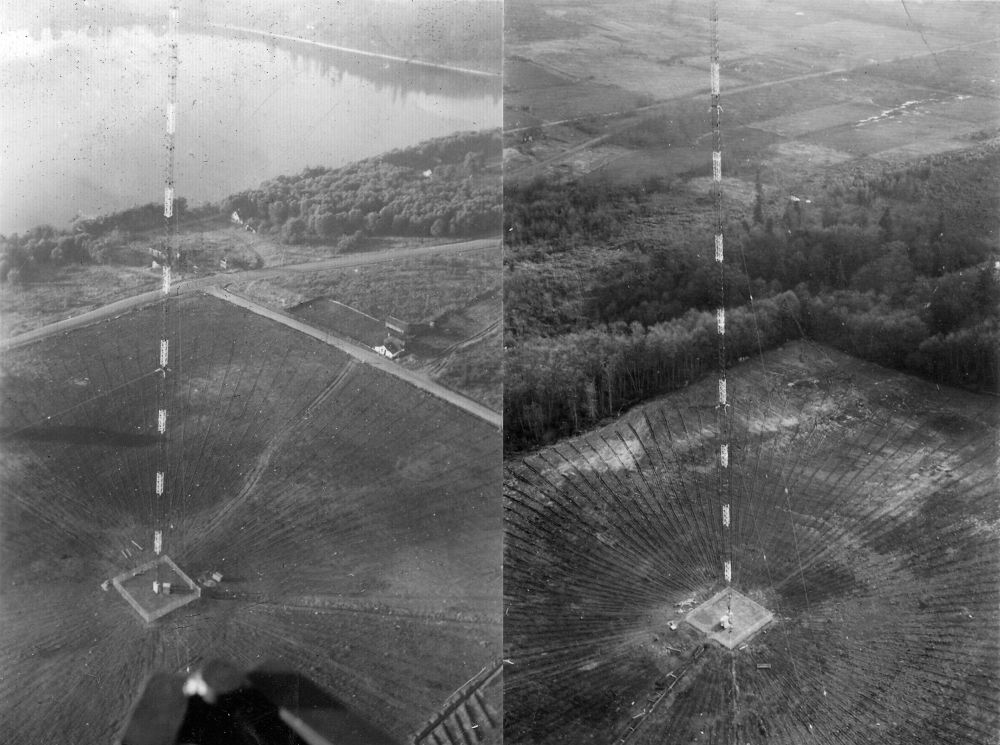

KIRO's two 526-foot Lehigh guyed towers formed the West Coast's first directional antenna system, directing KIRO's signal in a north-south direction. (Jim Hatfield photo)

This view shows the enclosure for one of the two antenna tuning units installed at the base of each tower. (Jim Hatfield photo)

Here is the construction crew installing the ground system for the KIRO towers. It consisted of 21 miles of one-inch copper ribbon, installed in 120 lengths of 420 feet each radiating from the bases of the two towers. (Jim Hatfield photo)

The new KIRO transmitter building on Maury Island, under construction. The fireproof reinforced concrete building was designed to resist enemy bombing - demonstrating the concern about Japanese agression in the pre-war Pacific Coast. (Jim Hatfield photo)

Here is the KIRO 50 kW transmitter building on Maury Island shortly after its completion in 1941. The building won an architectural award that year. KIRO was the first maximum power station in the Northwest, and only the fourth West of the Mississippi.

A 1944 aerial view of the KIRO transmitter building on Maury Island. It included living quarters for the engineers who manned the transmitter 24 hours a day. A garage and shop is at lower right. The white mast at right was an emergency antenna, built at the request of the Army Air Force should the main towers be bombed. (Jim Hatfield photo)

Aerial views of KIRO's two towers after installation. The trenches containing each tower's ground radials are clearly visible. (Jim Hatfield photos)

Here is a modern aerial view of the KIRO towers on Maury Island in the Puget Sound. The high-rise buildings of downtown Seattle are visible in the distance.

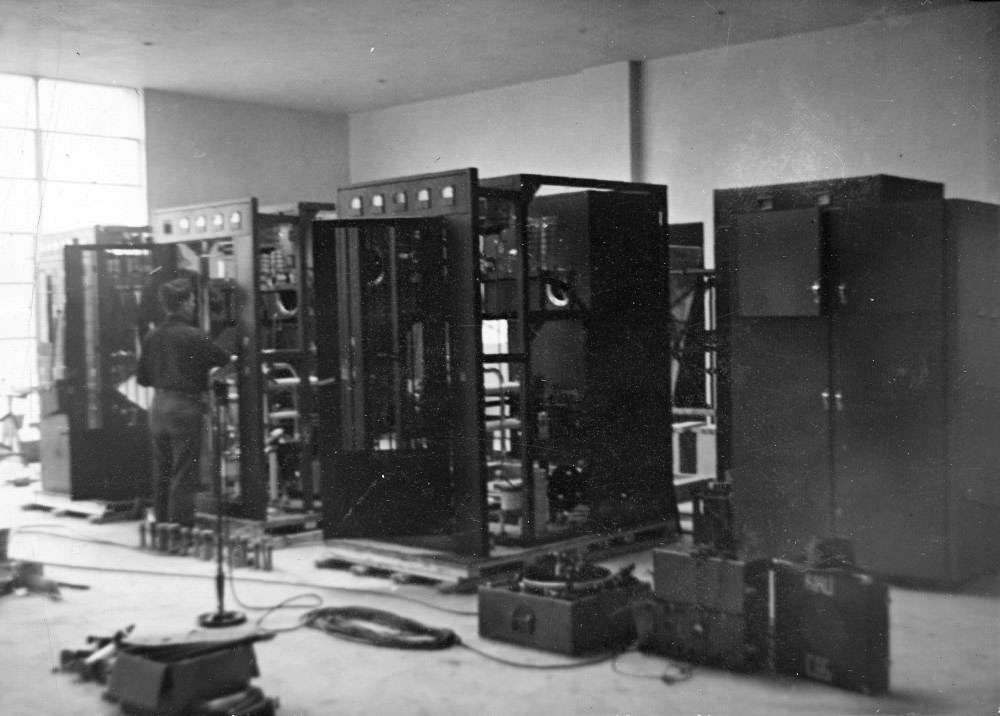

This snapshot shows the new Western Electric 50,000 watt transmitter in the process of being installed at KIRO. ((Jim Hatfield photo)

The new Western Electric 407-A4 transmitter was purchased from Graybar Electric for $51,000. The towers and ground system cost $32,400, and the building was $23,100. With ancillary expenses the total project came in at over $250,000 ($5.3 million in today’s dollars). (Hatfield and Dawson photo)

A closeup view of the transmitter control console that Western Electric supplied with its 407-A4 transmitter. Control desks like this managed the broadcast audio and the major functions of the transmitter. (Jim Hatfield photo)

Chief Engineer James B. Hatfield sits at the controls of the new transmitter, while soldiers from the 41st Infantry Division stand guard. Soldiers were deployed in 1941 to defend the coastline against a possible Japanese invasion, and KIRO was considered to be a critical wartime communications facility. (Hatfield and Dawson photo)

Chief Engineer James Hatfield shows one of the water-cooled tubes in KIRO's new transmitter to the U.W.'s "Queen of Queens" Doris Klemkaski, and Warner Brothers’ starlet Ella Raines. They were attending KIRO’s dedicatory broadcast on June 29, 1941. KIRO used two of these giant tubes, costing about $1,600 each in 1940s dollars. (Hatfield and Dawson photo)

AM directional antennas require field proof-of-performance measurements, and KIRO engineers spend many months traversing the coverage area to measure signal levels. This was complicated because so many of the required measurement points were in open water. Here James B. Hatfield makes signal strength measurements from a boat in the Puget Sound. (Jim Hatfield photo)

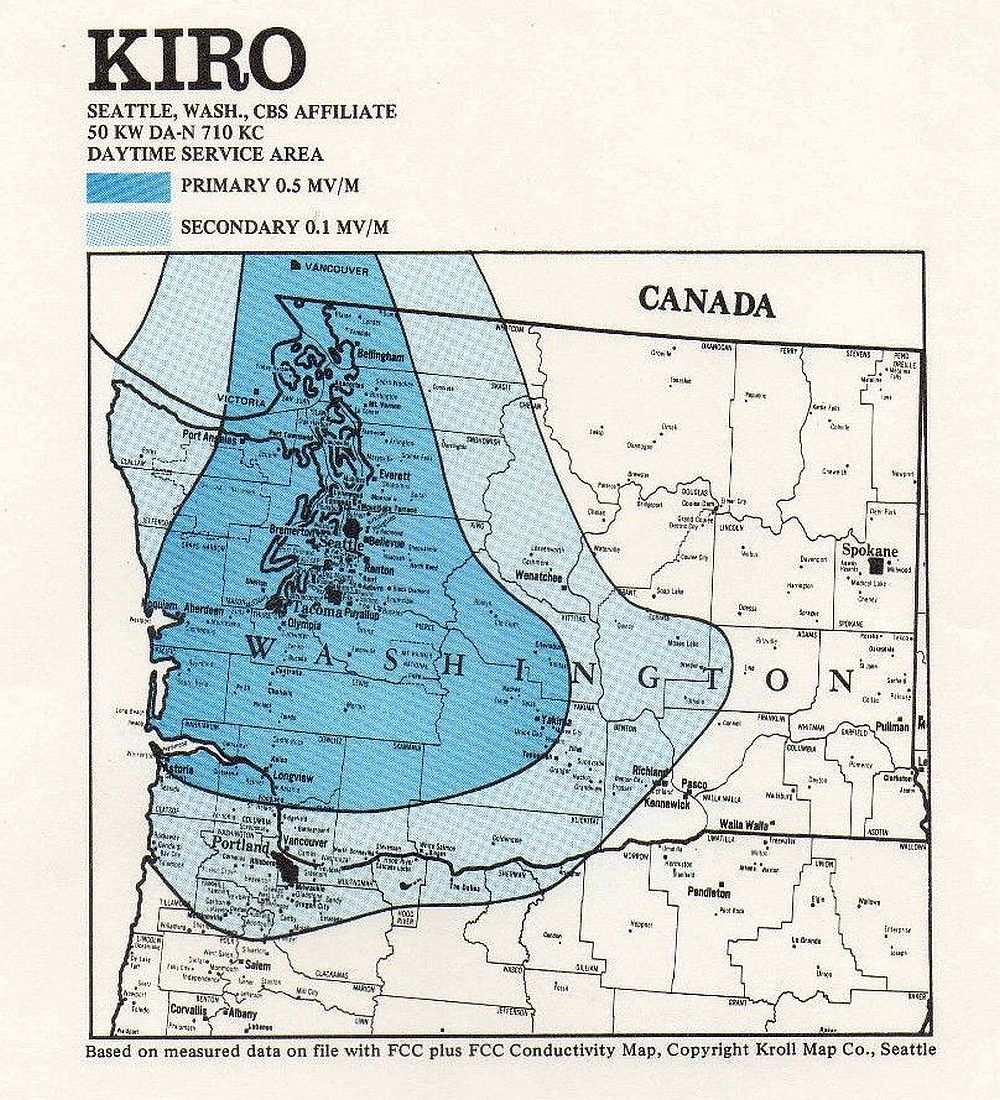

This KIRO coverage map shows the giant reach of KIRO's 50,000 watt signal, which was boosted by its directional antenna, salt-water location and low AM frequency.

This 1941 "Broadcasting" magazine advertisement promoted KIRO's increase to 50,000 watts.

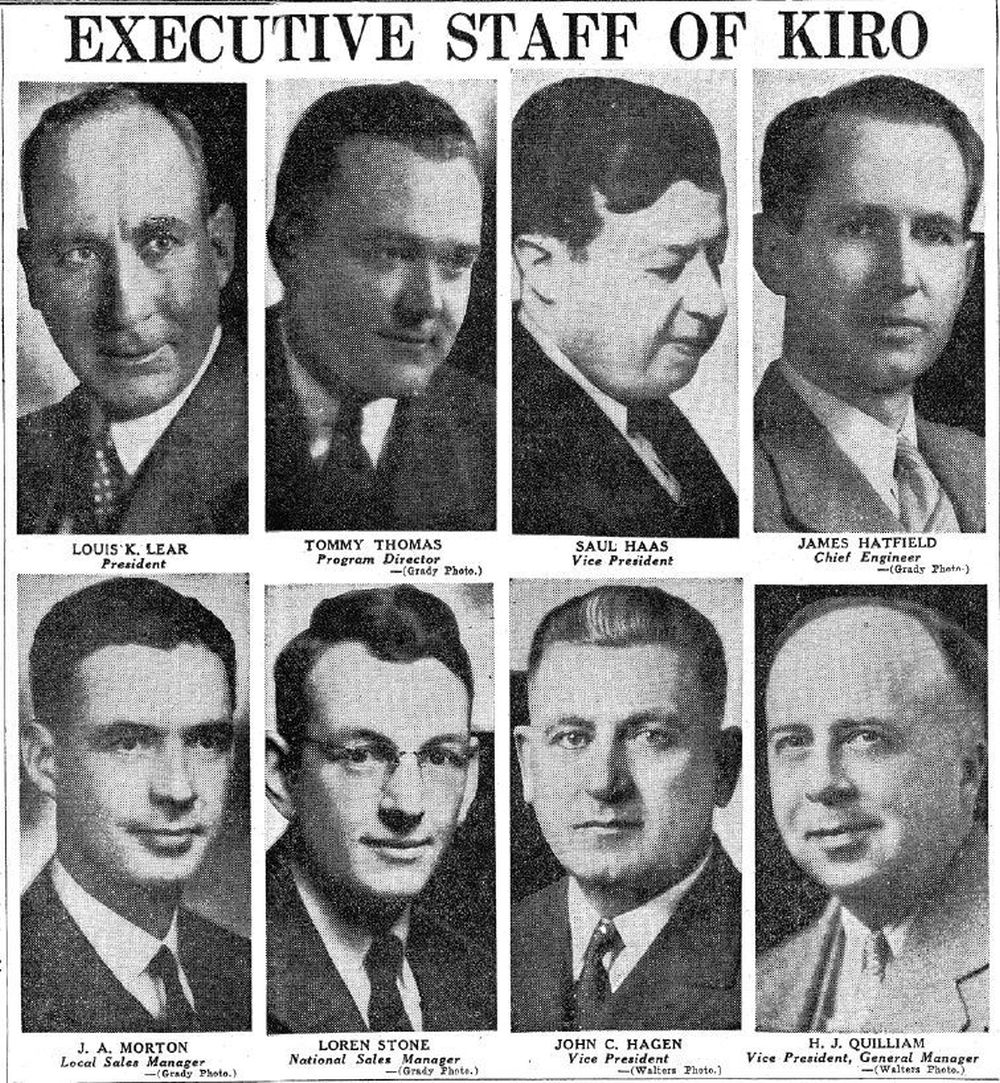

This was the executive staff of KIRO in 1941, as published in the Seattle Times in an issue celebrating KIRO's power increase. General Manager "Tubby" Quilliam was hired away from KOMO in 1935. He managed the station until 1945 when he left to buy his own station, KTBI in Tacoma.

Here was a KIRO mobile news station wagon parked on a mountain road, circa 1942. (MOHAI photo)

The patio behind the garage was often used for parties. Here are KIRO employees celebrating the station’s 15th anniversary on October 15, 1942. Among them are Engineer James Hatfield, Chief Announcer Maury Rider , Farm Editor Bill Moshier, Station Mgr. Loren Stone (station manager), General Mgr. Tubby Quilliam, and announcer Len Beardsley. (Jim Hatfield photo)

James Hatfield sets up for live broadcasts of the Silver Ski races from Mt. Rainier. The annual race began at 10,000 feet at Camp Muir and dropped 4,600 feet over ungroomed terrain, with skiers racing side by side. The races, held from the early thirties to 1948, ultimately ended due to tragic accidents and unpredictable weather. (Jim Hatfield photo)

KIRO bought the former Queen Anne Club building at 1530 Queen Anne Ave. N. in 1952. Built in 1927, the 12,000-square-foot building had a second-floor auditorium convertible into a TV studio. KIRO’s radio studios were on the first floor and offices on the second floor. However, KIRO was not able to acquire a TV license until 1957.

News Director Brice at KIRO-TV channel 7, 1960's. Saul Haas sold KIRO to Bonneville Broadcasting Co. in January of 1964.

KIRO morning man Jim French (standing) aired his program each morning for six years from this studio in the Space Needle. He is seen here with Mark Wayne (seated). This booth was first used by KING’s Frosty Fowler (see 2018 calendar), and was taken over by KIRO in 1966.

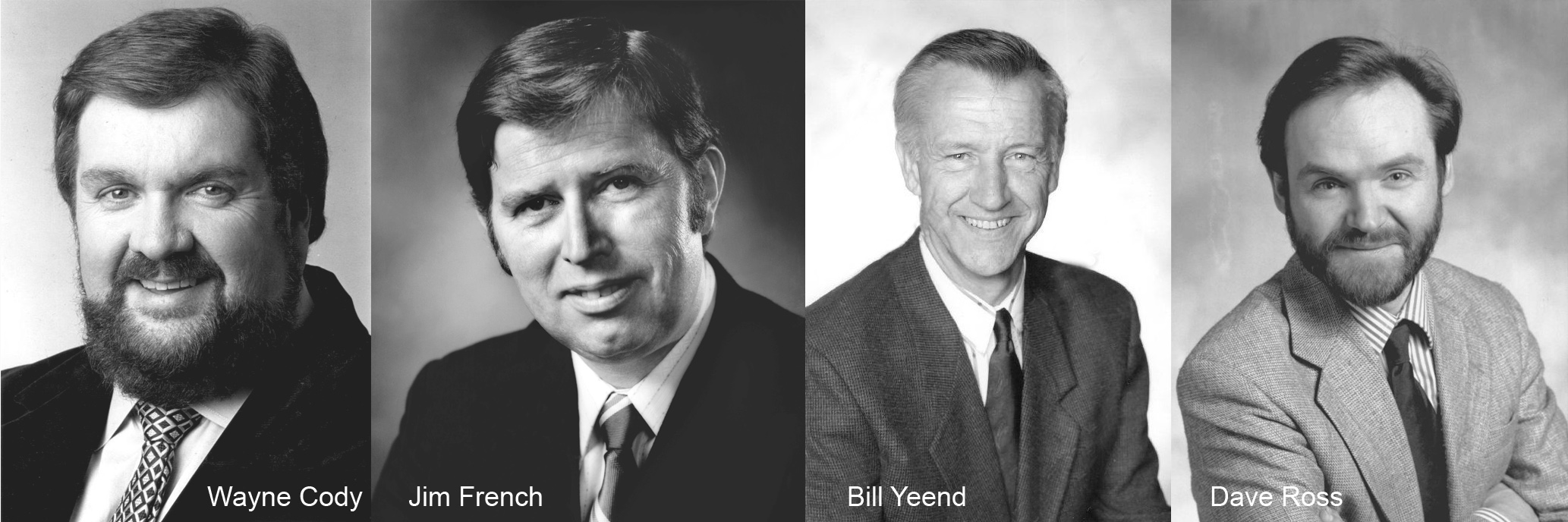

Some of KIRO's popular on-air personalities in the 1970s and 1980s. Cody was the station's sports director in those years; French was a popular voice whose 42-year career bounced between KIRO and KVI. Bill Yeend was KIRO's morning news voice for 27 years. That spot is now occupied by Dave Ross, who joined KIRO as a news anchor in 1978.

Paul Brendle was the pilot of KIRO's Enstrom traffic copter from 1978 to 1997.

Here is a recent view inside the KIRO transmitter building. The enclosure that formerly enclosed the Western Electric transmitter now houses audio, monitoring and ancillary equipment. The current transmitter, a Nautel solid state model, is out of view. (Society of Broadcast Engineers photo)