In March of 1925, Birt F. Fisher leased jailed bootleger Roy Olmstead’s KFQX and returned it to the air as KTCL (“The Charmed Land”), moving the transmitter to Magnolia Bluff and with studios in the New Washington Hotel. Fisher attempted to broadcast quality local programs but continually suffered financial and technical setbacks. In April, 1926, KTCL was evicted from the hotel and was silent for several weeks while moving to the Home Savings and Loan Building.

But the worst of Fisher’s problems came in May, 1926. To pay his $8,000 liquor law violation fine, Olmstead sold KCTL to Vincent Kraft, the owner of KJR, for $10,000. Kraft planned to take over the station once Fisher’s lease expired in December.

Fisher scrambled to find a solution to his dilemma. He knew that one of the owners of Fisher Flouring Mills, Oliver David (O.D.) Fisher (no relation to himself), was a big radio fan, so he approached the Fisher family seeking financing for a new station. O.D. and his brother Will agreed to form Fisher’s Blend Station, Inc., owned 66% by the Fisher brothers and 34% by Birt Fisher. Their plan was to transfer the KCTL operations to a new station when the lease expired. A new Western Electric 1,000 watt transmitter was installed at the Fisher flour mill. Temporary studios were set up in the 303 Westlake Square Building until permanent facilities in the Cobb building could be ready the following year. The new station debuted as KOMO on New Years’ Eve, 1926 with an all-day inaugural extravaganza involving over 250 people, including a new full-time KOMO orchestra. That same week, Kraft took over the old KTCL and changed its call sign to KXA.

KOMO was conceived as a promotional vehicle for Fisher’s Blend flour, which was responsible for part of the program schedule. For the remaining time, a new corporation named the Totem Broadcasters was formed, owned by twelve of Seattle’s largest businesses. Each member committed to sponsor part of the remaining air time in exchange for air mention.

With a staff of 65 producing fourteen hours of live programs a day, and soon to be chosen as the local NBC network affiliate, KOMO quickly became one of Seattle’s most popular stations.

(From the book "Seattle Radio" by John Schneider, 2013.

Brothers O.W. and O.D. Fisher opened the Fisher’s Blend Flouring Mills on Harbor Island in 1911 – an artificial island at the mouth of the Duwamish River in Elliott Bay. Here is one of the company’s new 11½-ton delivery trucks on West Spokane Street near Whatcom Avenue in 1918. (Seattle Municipal Archives photo)

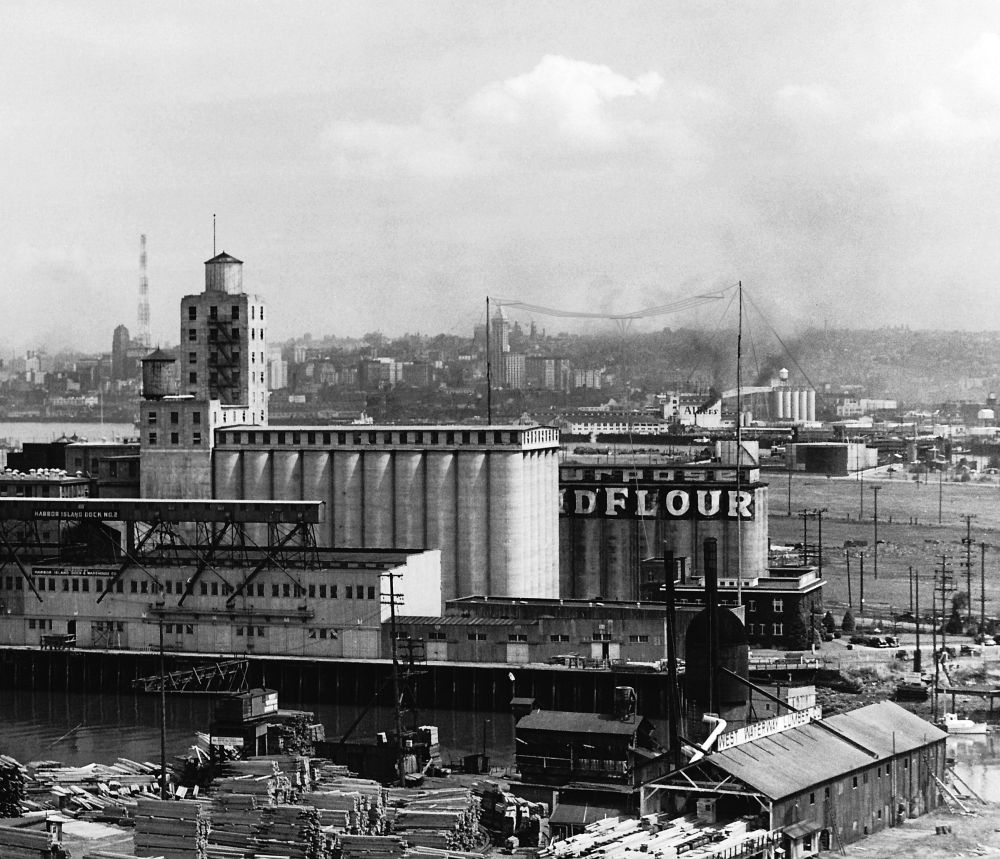

The Fisher Flouring Mills, a prominent landmark on the Duwamish Waterway, was the location of the KOMO antenna in 1926, seen here suspended between two wooden poles. The brick building at right housed the transmitter. (The KOL tower is in the background.) This antenna was replaced in 1937, but the mill buildings and silos are still in use today.

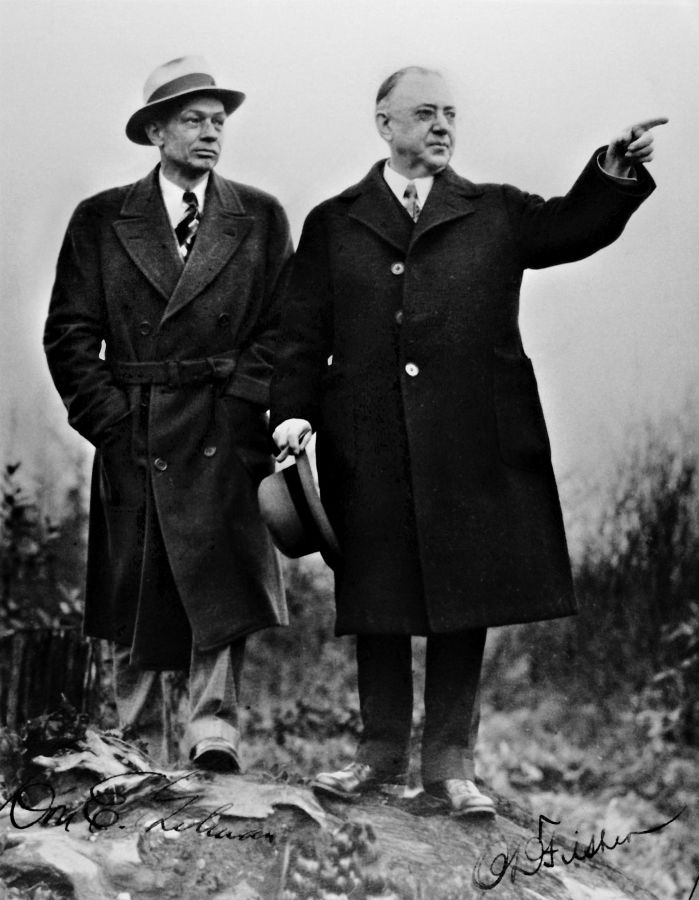

Oliver David (O.D.) Fisher was the principal owner of Fisher’s Blend Station, the operator of KOMO. In 1933, Fisher’s Blend leased KJR from NBC for $1 a year and operated both stations from studios in the Skinner Building. Here is O.D. with Don E. Gilman (left), the Western Division manager of NBC, in the 1930s.

Birt Farrington Fisher (1886-1961) leased the Olmstead station KFQX in 1925, changing it to KTCL. In 1926 he joined with O.D. Fisher to form Fisher’s Blend Station, opening a new station, KOMO. Birt Fisher was the manager of the new station. In 1933, Fisher’s Blend leased KJR from NBC, and purchased it in 1941. When the FCC forced the two stations to separate in 1945, Birt Fisher became the sole owner of KJR.

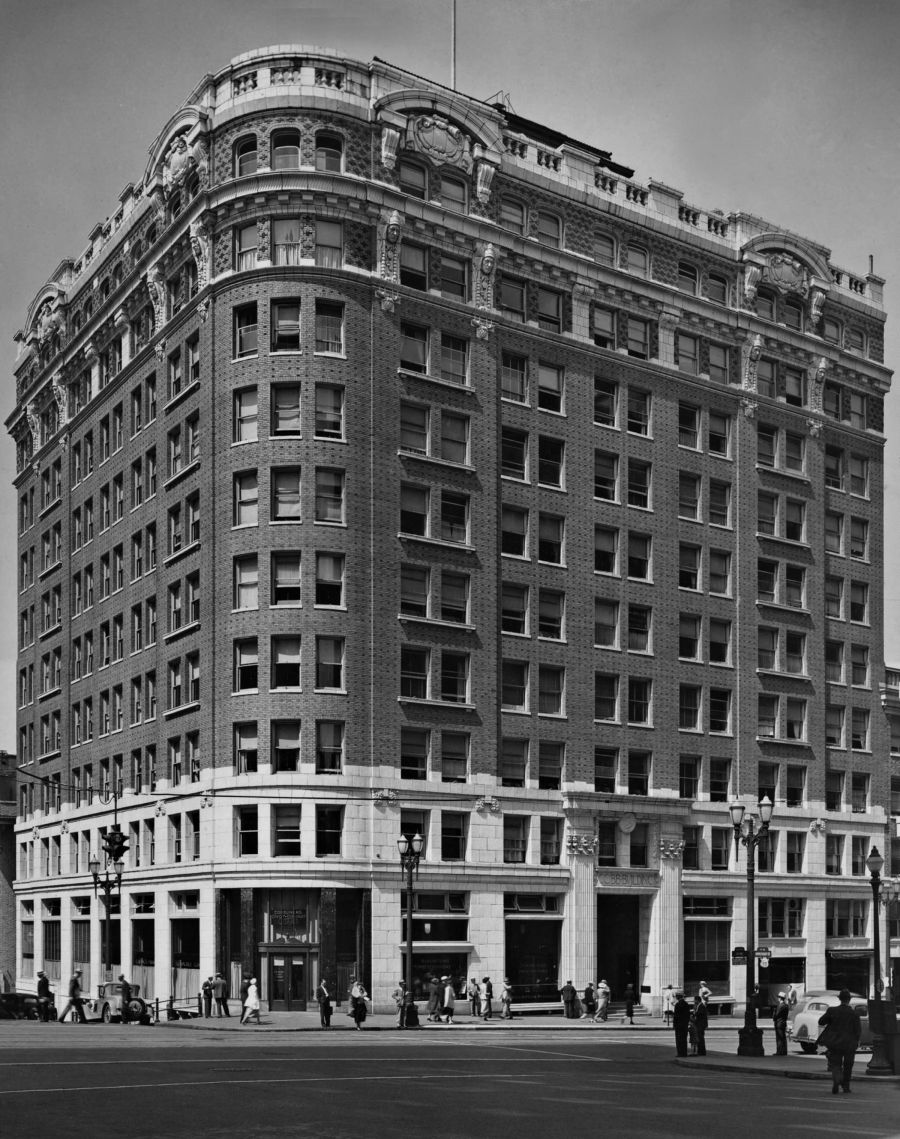

In 1927, KOMO moved into basement studios in the Cobb Building at Fourth and University. This imposing Beaux Arts edifice was built in 1910 by the Metropolitan Building Company, in which the Fishers were investors. In 1933, KOMO took over the operation of KJR and both stations moved into the Skinner Building. KIRO then occupied the Cobb Building studios through the 1940s. The Cobb Building was converted into apartments in 2005. (Seattle Public Library photo)

The entire KOMO program staff assembled for this photo in the Cobb Building studio, under the banner of the "Totem Broadcasters", in 1927. Totem was a production company by that name, operated by twelve of the largest businesses in the area. Each company guaranteed a certain amount of sponsorship, taking responsibility for producing most of KOMO's local programming. (MOHAI photo)

An unidentified pianist performs in the KOMO studios in the Cobb Building, at Fourth and University Streets in downtown Seattle. Seen in this view are a piano, organ, a signaling lamp fixture, and a bird cage. The sound of singing canaries was often heard in the background during KOMO's early days. (MOHAI photo)

Art Lindsay and Gladys Everett, the two pictured, were known as the "KOMO Harmony Team". Here they are in the KOMO studios in April 1929.

Post-Intelligencer’s sports editor and local sporting icon Royal Brougham interviews heavyweight boxer Jack Dempsey on KOMO during the late 1920s. The Manassa Mauler" was the losing protagonist in two historic boxing matches against Gene Tunney that were broadcast nationwide in 1926 and 1927, making him one of radio's earliest celebrities.

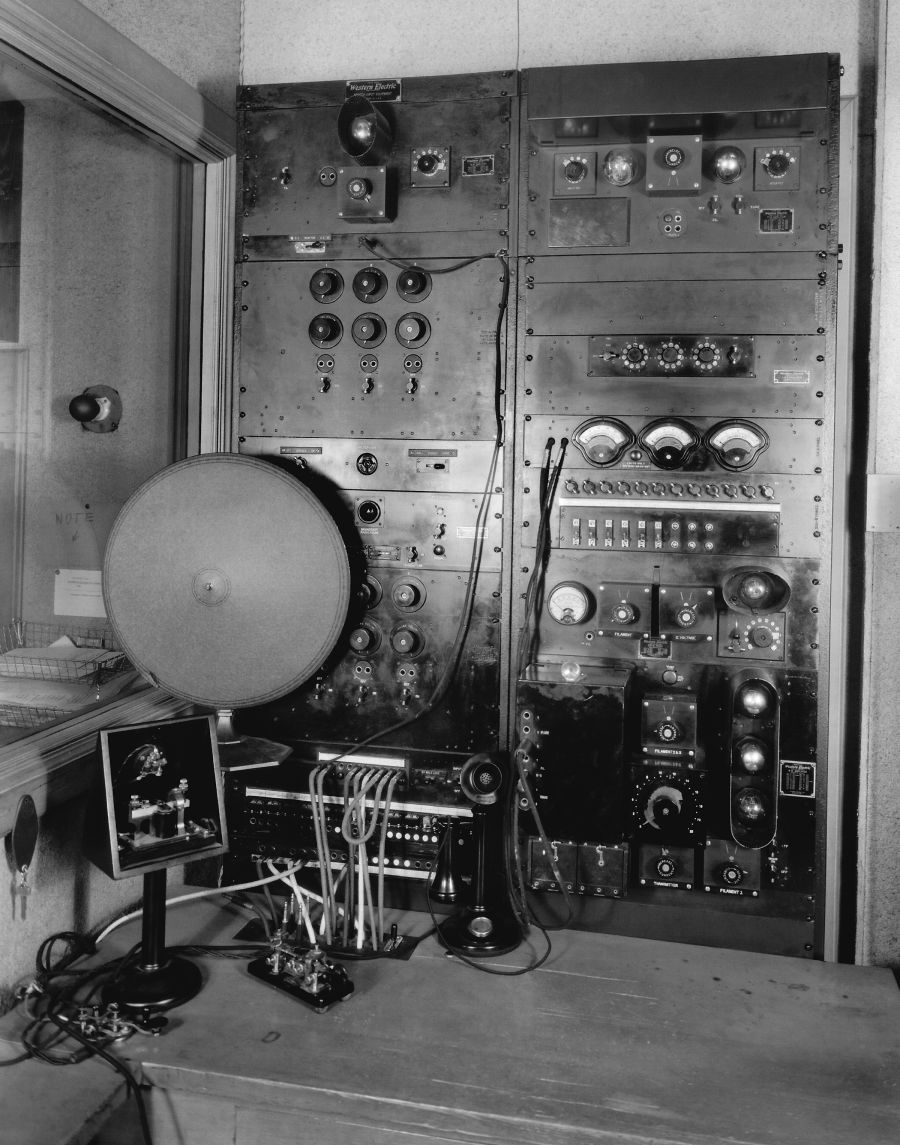

Here is the KOMO master control room in the Cobb Building, about 1927. The control operator selected the studios and microphones to be broadcast and controlled the overall program volume. A paper cone monitor speaker is at center left, with a telegraph sounder below it. (MOHAI photo)

This was the Skinner Building at 1326 Fifth Avenue, shortly after its completion in 1928. The Fifth Avenue Theater was on the ground floor, and the KOMO-KJR studios were on the two top floors. The Fisher family was a major investor in the Metropolitan Building Company, the developer of the Metropolitan Tract in downtown Seattle and also owner of the Skinner Building. (MOHAI photo)

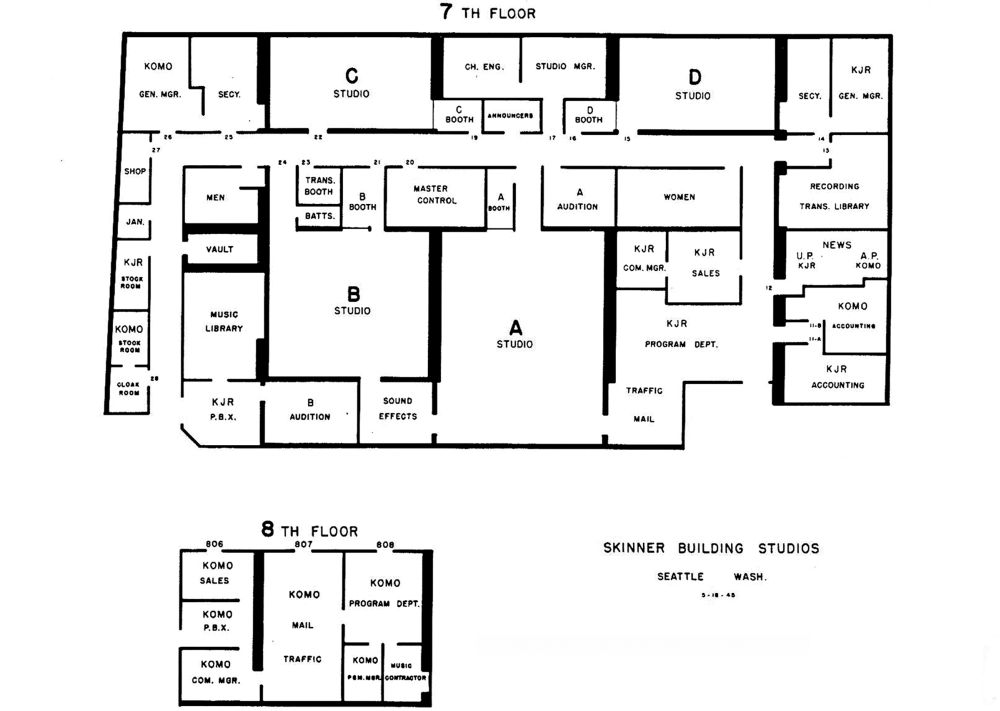

This floor plan shows the layout of the Skinner Building studios. KOMO and KJR shared the four studios. Studios C and D were large enough for full orchestras or dramatic casts, but were mostly the source of piano performances and news programs. The Big A and B studios, used for live productions, floated on six inches of balsa wood to isolate them from any outside sounds.

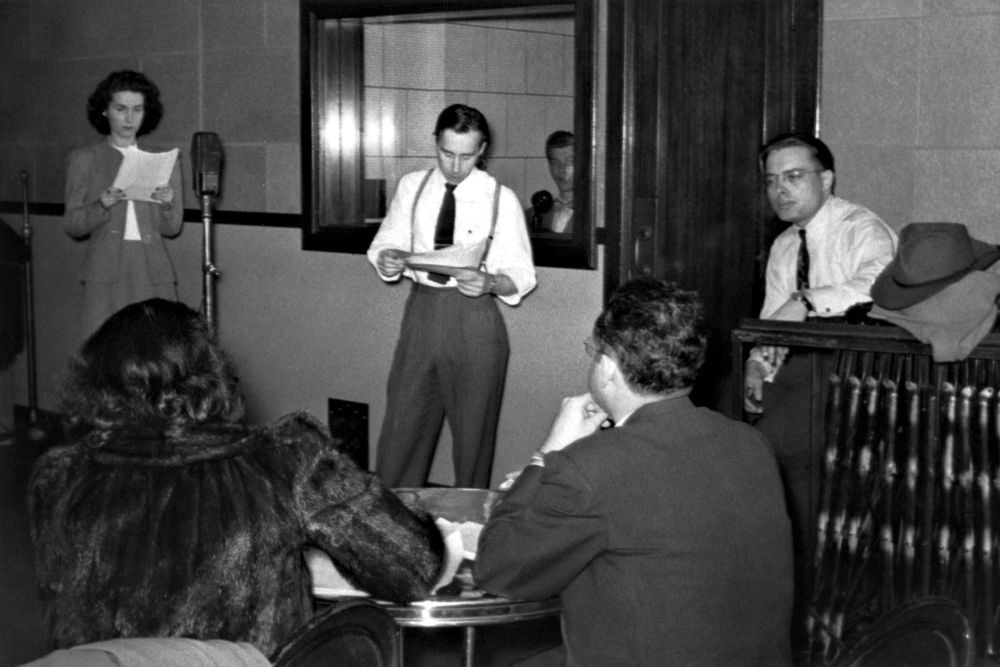

This 1937 photo shows the KOMO-KJR staff rehearsing for a broadcast in Studio “A” of the Skinner Building. A mobile turntable cart is available to produce recorded sound effects, and a number of devices for the creation of live effects are on hand. (MOHAI photo)

Although most of the programs heard on KOMO and KJR came from the NBC Red and Blue networks, locally produced programs were an important part of the schedule. This undated candid snapshot shows a production of the “KOMO Northwest Theater” with Al Morris, Bob Hurd, Lis Leonard, and Dale Smith.

Producer Bob Hurd is seen in another candid snapshot. It is an unidentified KOMO-KJR production with radio actor Don Driver. Hurd is operating the sound effects turntable cart.

KOMO’s Grant Merrill interviews Washington resident and author Betty MacDonald, about 1945. Her first book, "The Egg and I", was an instant hit and sold a million copies its first year. Merrill started in radio as a pianist on KJR in 1928, and rose to position of production director with the combined KOMO-KJR.

Merrill Mael began his radio career at KEVR and KOL in Seattle in 1939, moving up to KOMO-KJR and then on to NBC in Hollywood in 1941, where his resonant voice was heard on a number of network shows. After many years working in Alaska broadcasting, he returned to the Puget Sound area as a financial consultant.

Here is Morton Presting announcing a program in the Skinner Building, about 1941. Presting was later a supervisor for Far East programs for the Voice of America, and was responsible for broadcasts to Korea during the Korean War.

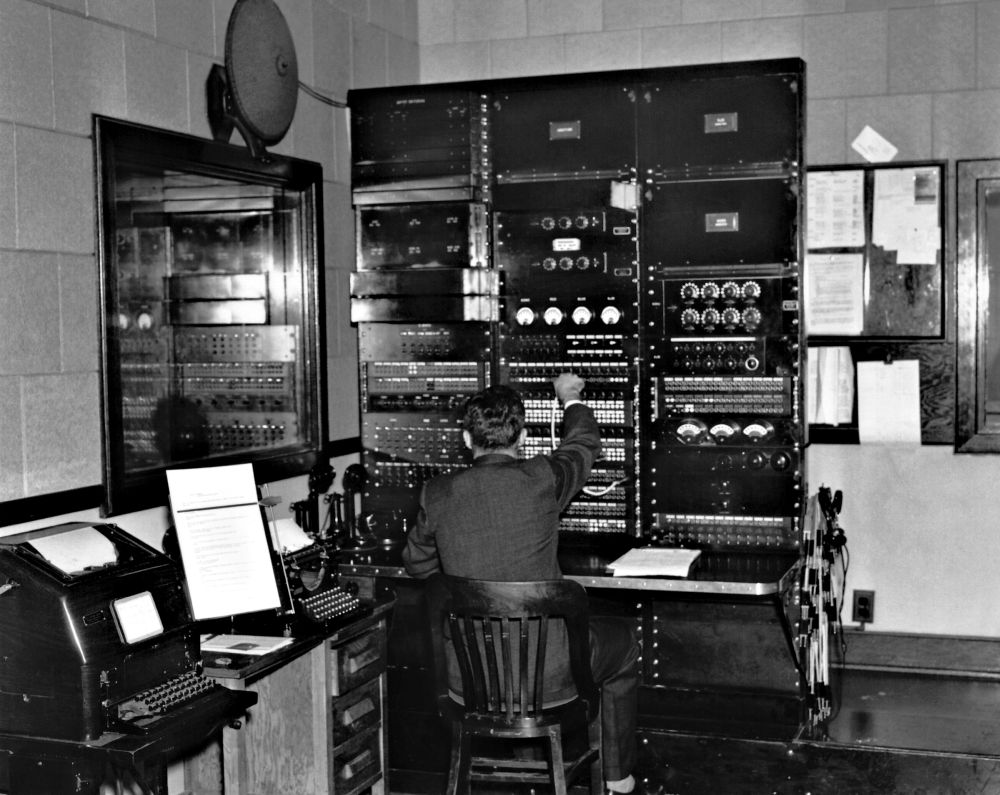

This was the KOMO-KJR master control room in 1937. The operator here was responsible for the final quality and routing of the program audio as it left the building and went to the transmitters of both stations. He could also switch rehearsal audio to the audition rooms, or send audio from any studio to the transcription room for recording. (MOHAI photo)

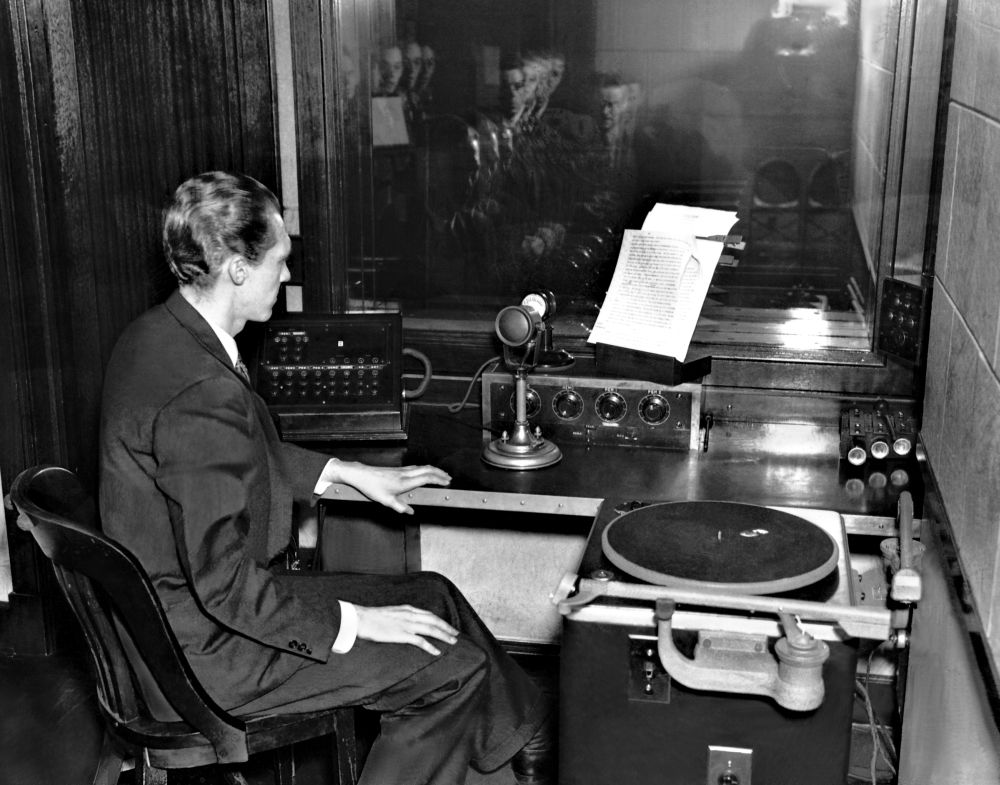

Each KOMO-KJR studio had a control booth that oversaw the performance through a plate glass window. Here is Clinton Johnson in one of the booths in 1937. Each room had a small mixing console, turntable, microphone and a switching control box that selected outside program sources (network or remote broadcast phone lines) and could feed programs to either station. (MOHAI photo)

In October of 1939, a new Wurlitzer three-manual pipe organ was installed in Studio B of the Skinner Building. The custom-built instrument was installed by Balcolm and Vaughn, Seattle master organ builders. The entire console was mounted on wheels to make it movable within the studio. The complete installation took eleven weeks. Ed Zollman is seen here at the keyboard.

Hugh Barrett Dobbs ("Dobbsie") hosts the Ship of Joy program, mornings on KOMO. Here he swaps stories about knots with Warren Barde, a Seattle Sea Scout. Dobbsie hosted a special scouting program in 1940 on KOMO, saluting the annual Scout Circus at the U/W Athletic Pavilion.

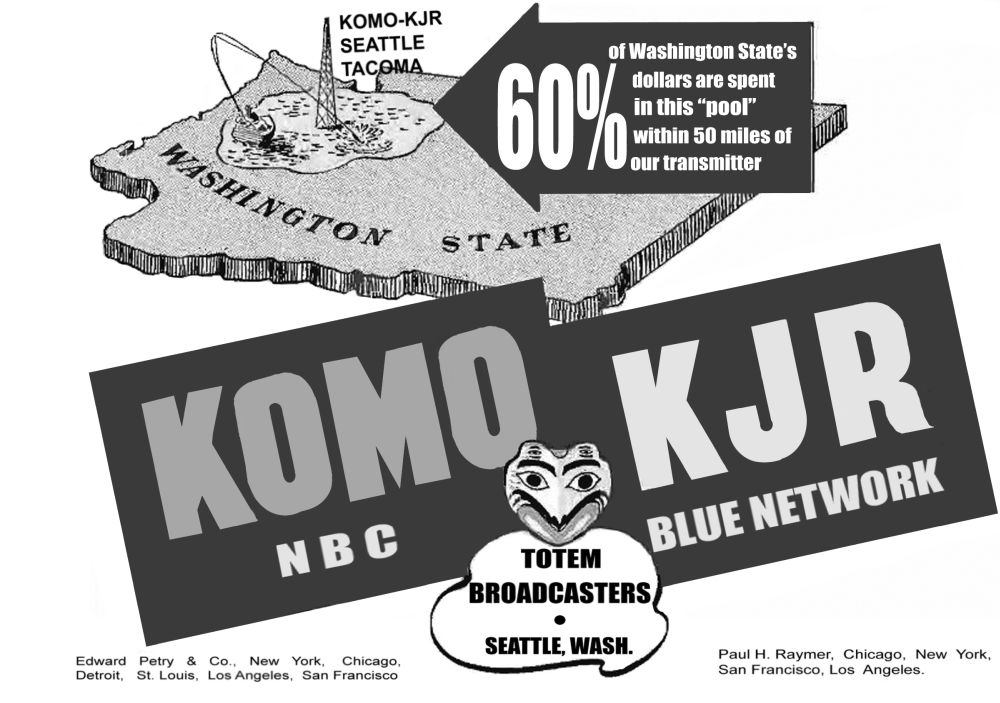

This advertisement for the two Totem Broadcasters stations appeared in Broadcasting Magazine in 1941. As the local affiliates for both the NBC Red and Blue networks, KOMO and KJR had a lock on most of the nation's best radio programming, and so the stations attracted much valuable national advertising while the smaller Seattle stations survived mostly on local advertising.

This 573 foot tower on the West Seattle waterway was completed late in 1936. It was a shared transmitter site for Fisher Broadcasting Company's two stations, KOMO and KJR, and both operated with 5,000 watts from the same tower. This aerial view above was taken right after the tower's completion, and shows some of Seattle's "Hooverville" squatter's cabins at the water's edge.

Here is the West Seattle tower in December, 1964. In 1948, KOMO increased its power to 50,000 watts and moved to a new site on Vashon Island. KJR continued to operate from this tower and later moved its studios here in 1955. A smaller second tower was added to allow KJR to increase its nighttime power. KJR finally vacated the site in 1996, and the landmark Truscon tower was dismantled in 2000.

This was the KOMO-KJR transmitter staff at the West Waterway site at 2600 26th SW: L-R: Lawrence "Whitey" White, Tommy Rewak, Fred Berry, Johnny Vinem, Ernie Rasmussen, Bob Smith, Chief Engineer Francis S. Brott, an unidentified engineer, Bob Walker, Clarence Clark, Louis Greenway, and Harold Koontz.

In 1945, the FCC’s new duopoly rule prohibited the ownership of two stations in a single community, forcing KOMO and KJR to separate. This ceremony in November, 1945, marked the separation of the two stations. Birt Fisher became the 100% owner of KJR in a stock swap, with no money changing hands. (L-R) O. W. Fisher, president of KOMO; Marion Bush, his secretary; Jean Wylie, Birt Fisher’s secretary; and Birt R. Fisher.

After four years of planning and construction, KOMO moved into this imposing three-story broadcast center at Fourth Avenue and Denny Way in early 1948. The $750,000 structure was built as a magnificent radio palace, but was also planned to accommodate a future television station. In 1953, KOMO-TV went on the air from the building, and the combined radio-TV broadcast plant would stand for 40 years.

This night view of the KOMO building on Denny Way shows members of the public lining up for a tour of the building during its grand opening.

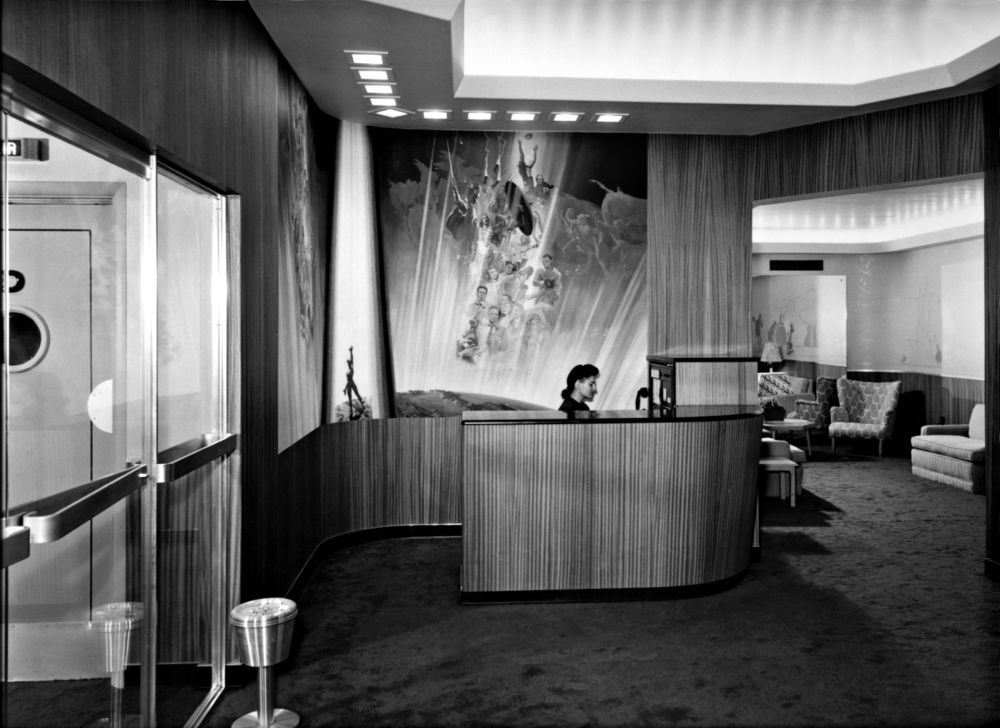

This is a view of the lobby and reception area in the KOMO Denny Way building. The mirrored waiting room can be seen in the background. The glass doors to the left led to the operations center and onward to the studios.

Artist E. T. Grigware's impressive mural "Across Horizons" that graced the building's lobby entrance during the entire life of the building. (Photo courtesy of Jim Bach)

These glass windows gave a glimpse into the station's main operations center. Its occupants had a direct view into the master control room (front cover) and overlooked the entrances to all five studios on the main floor. In later years, this would become the KOMO news room. Caricatures of famous NBC performers and artists decorated the hallways.

This view of Studio B shows the music director's booth on the left, the control room in the center, and the sponsor's booth above the control room. The plywood semi-cylindrical baffles dispersed acoustic reverberations. The floors floated on springs with felt isolators, and the ceiling was suspended from the building framework. The Wurlitzer organ was moved over from the Skinner Building.

Studio C was slightly smaller, but was still capable of holding a medium sized music ensemble. A window on the right-wall led to the music director's booth, which looked into both large studios. This was done so that complex programs could utilize both studios, with an orchestra in the larger studio and the actors and announcers in the smaller studio. When KOMO-TV was built, both "B" and "C" became TV studios.

This large studio in the basement of the KOMO building featured audience seating. The control room operator had a view of both the stage and the audience. Theater lighting spotlights were mounted in the ceiling. In later years this room was converted into an auxiliary TV studio, and then was finally divided up into offices.

In announce studio E, the announcer has a view into either of its two shared control rooms. The heavy isolated doors with their porthole windows were the classic 1940s studio doors. Jack Kerr is the operator seen through the window in this picture; the announcer is not identified.

Each studio had its own dedicated control room. The exceptions were the small announcer studios E and F, which shared a single control room, seen here. There was also one control room for studios D and E, arranged so the two control rooms served three studios, and any combination of two could be on the air at the same time.

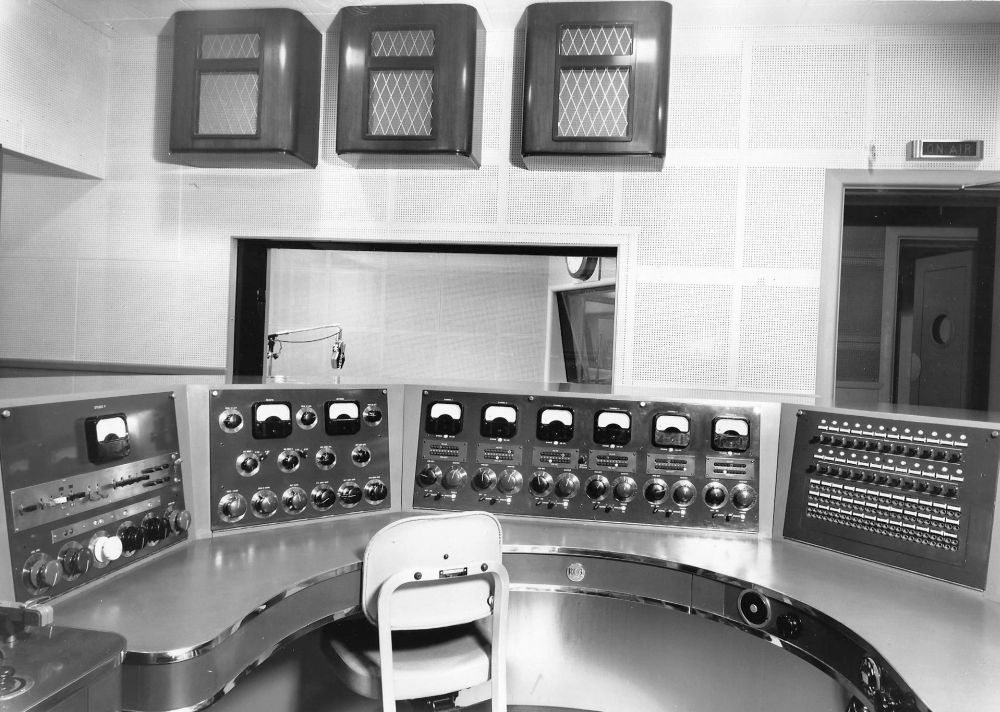

This was the KOMO master control room when the building first opened. The audio from all studios came here, along with the NBC network and remote broadcast lines. The operator at this desk controlled everything that was heard on the air.

Another view of the KOMO master control room, showing the custom-manufactured RCA audio control panels.

The 600 ft. KOMO-FM tower was constructed on the North side of the studio building in 1949. It was also planned as the support for a KOMO-TV antenna, but Fisher Broadcasting did not obtain a TV license until 1953. When that happened, KOMO-FM was shut down because of financial losses and the tower was moved to Queen Anne Hill for KOMO-TV.

In 1947, KOMO achieved a long-sought power increase and built this new transmitter plant on Vashon Island. The three tower directional antenna system occupied 77 acres of Vashon Island real estate. KOMO began regular operation from this site in April, 1948.

The new RCA BTA-50F transmitter was so large that the building was literally built around the transmitter, and had separate rooms to hold the ventilation fans and transformers. It was one of the first big post-war transmitters to be delivered by RCA. (Photo courtesy of Walt Jameson)

This 1949 view shows the interior of the KOMO-AM transmitter building, with its imposing RCA BTA-50F transmitter.

The transmitter engineer's desk in the center of the room held the operator's console, giving him hands-on control of the main transmitter functions plus the program audio. To his far right was the antenna "phasor", which created the station's directional radiating pattern by controlling the amount of power fed to each of the three towers on the property.

Another view of the transmitter control room shows the program audio rack cabinets at left. For an unexplained reason, this view shows two identical transmitter control panels.

This more recent view of the RCA BTA-50F transmitter shows off the RCA colors and art deco styling of its cabinet. The transmitter was meticulously maintained by the KOMO engineers and kept in operation into the 1990's.

An interior view of the BTA-50F transmitter shows the RCA 5671 final amplifier tubes. Two of the tubes were used in operation, and the other two were spares that could be switched in if a main tube failed. Four more 5671 tubes were used as modulators, with one spare. These tubes were so heavy that a specially-designed forklift was needed to change tubes.

The BTA-50F was a "walk-in" transmitter. Doors in the front of the cabinet provided access to its roomy interior.

This view shows the large modulation transformer and modulation choke in the interior of KOMO's BTA-50F transmitter.

Here were some of KOMO's popular air personalities during the 1970's. Seated is Larry Nelson, KOMO's top-rated morning personality. Nelson retired form KOMO-1000 in 1997 after 30 years as the morning man and died in 2007. Standing behind him is Norm Gregory, another popular local personality who enjoyed a long career on several stations.