A COMPLETE HISTORY OF

KFWB,

HOLLYWOOD, CALIFORNIA

By Jim Hilliker, © 2015

|

|

A COMPLETE HISTORY OF

KFWB, By Jim Hilliker, © 2015 |

|

www.theradiohistorian.org Copyright 2023 - John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC (Click on photos to enlarge)

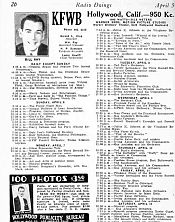

KFWB helped capture a murder suspect. Click here for the entire article.  KFWB program schedule, 1930.

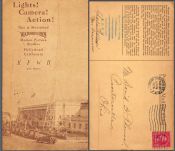

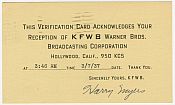

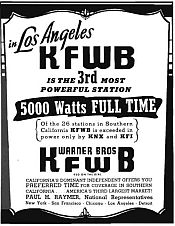

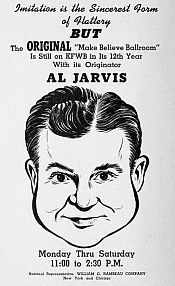

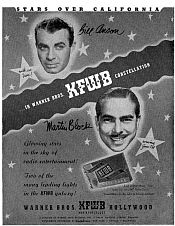

Another view of the KFWB antenna on Hollywood Blvd.  KFWB advertising contract, 1929.  KFWB QSL card, 1926  KFWB QSL card, 1937.  Ronald Reagan holding a KFWB microphone talking to two Alabama players before the New Years Day Rose Bowl game against California. December 1937.  KFWB children's Halloween party, hosted by "Uncle John" Daggett. Children who had appeared on his "Uncle John's Junior Review" program during the year were invited - October 29, 1937.  KFWB transmitter building, Baldwin Hills, 1937.  1936 advertisement, announcing KFWB's night-time power increase to 5,000 watts.  1945 Advertisement for DJ Al Jarvis.  KFWB advertisement featuring Martin Block, 1947.  Hal Styles with the Los Angeles Fire Department.

|

|

THE ONLY MOVIE STUDIO TO OWN A RADIO STATION It was the night of March 4, 1925 that the motion picture industry and the very new radio broadcasting industry joined forces to promote one another. On that night at 7:00 p.m., the Warner Brothers Motion Picture Studio’s new radio station, KFWB, made its debut broadcast. The new radio station was located on the movie studio lot at 5842 Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood. Its original output power was 500 watts and its frequency was 1190 on the AM dial. Movie fans were able to tune-in as Warner Brothers used the station to present its actors and actresses to the radio microphone and promote the studio and the latest Warner Brothers films. When radio first got the American public’s attention in 1922, the movie studios took notice. That year, a movie serial was filmed called “The Radio King.” The titles of some of the chapters in the serial included “The Secret of the Air,” “Warned by Radio,” and “Saved by Wireless.” Scenes that featured a typical living room in an American home began to show a radio in some of the movies made at the time, too. In 1925, the year KFWB went on the air, the Hal Roach Studios hired the most popular radio announcer in Los Angeles to appear in a scene in an “Our Gang” comedy short. The film was called “Mary, Queen of Tots.” The plot included the kids being scared by what they heard over the air in a radio play. John S. Daggett, also known as “Uncle John” on KHJ’s children’s program, was KHJ station manager and main announcer from 1922 until 1927. He played himself in the movie in a scene which was supposed to be a KHJ broadcasting studio. This may have been the first time that a radio announcer played himself in a movie. Movie fan magazines had been around for a long time by 1925. But now, with the Warner Brothers movie studio owning their own radio station, KFWB began heavily promoting each movie and its stars, as the studio released each film to the public. The promotion of new movies is such a big business today, that we seem to be flooded with entertainment programs that concentrate on nothing but movie and TV actors, singers, their work and gossip about their personal lives. With KFWB, Warner Brothers focused only on their own movies and actors and actresses. The station used them in Variety and dramatic programs and got their names and voices out to the radio listening public. This was all quite new and exciting to movie fans of this era, especially in the years just before talking movies were introduced. But KFWB also made blocks of time available to other movie studios to showcase their actors and films. KFWB was the first and only radio station to be owned by a movie studio until 1948, when MGM Studio put FM station KMGM on the air at 98.7 MHz. (That short-lived station was taken off the air in 1953 by MGM. A new station license was granted for 98.7 FM in 1954 as KCBH call letters are now KYSR, known better as ALT. 98.7). SOME EARLY TECHNICAL HISTORY KFWB’s 4-wire antenna supported by two 150-foot towers was in front of the Warner Brothers building on Sunset Blvd. After first broadcasting on 1190 kilocycles in 1925, KFWB was moved from 1190 to 830 on the radio dial on June 15, 1927. In February of 1928, the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) assigned KFWB to broadcast on 850 kilocycles, but one month later, moved the station back to 830 on the dial. Also in March of 1928, KFWB increased its transmitter power from 500 to 1,000 watts. On November 11, 1928, as part of the national restructuring of the Broadcast Band (AM) by the Federal Radio Commission, KFWB moved from 830 to 950 kHz. With that move to 950, KFWB was forced to share a small portion of its broadcast day with the Pasadena Star-News station KPSN; this lasted for one year, until November 15, 1929. During this period, KPSN, which went off the air in 1931, was given only 30 minutes to one hour of air time each day, and KFWB was able to broadcast the remainder of its hours. By the 1936, KFWB was operating with 5,000 watts day and 1,000 watts at night, from 6:30 am until midnight and on Sundays from 8 am until midnight. In 1939, the nighttime transmitter power was raised to 5,000 watts. On March 29, 1941, KFWB changed its frequency again, from 950 to the current 980 kHz. HOW WARNER BROTHERS STUDIO GOT INTO RADIO The 1920s was a tumultuous decade for radio, as broadcasting was just beginning to evolve. When KFWB went on the air, only 14.4 percent of American homes had a radio. As the technology rapidly matured, the types of radios sold to the public were changing yearly, along with the radio station equipment and the way stations presented their programs over the air. The early radio listeners in Southern California, who in many cases were also movie fans, tuned in at every opportunity to hear a variety of screen actors speak over KFI, KNX and KHJ.. Many of the most famous movie stars of the day such as Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, John Barrymore, Conrad Nagel and even child actors such as Jackie Coogan and Richard Headrick had been heard on those stations. According to one book about the Warner Brothers movie studio, two of the four Warner Brothers -- Sam and Jack Warner -- had heard the broadcasts from local stations like KFI, KHJ and KNX. They quickly noticed that some of their movie studio competitors were using local radio to advertise and publicize their films. So, the Warner Brothers decided they needed their own radio station. When they couldn’t buy one that was already on the air, they decided by early 1925 to build a new station. KFWB’s first 500-watt transmitter was obtained from KFI, which had purchased the Western Electric transmitter in 1923. They sold it to Warner Brothers because KFI was buying a new 5,000 watt transmitter. By 1931, after KFWB had increased power to 1,000 watts, they sold the same 500-watt transmitter to a station in Portland, Oregon. Sam Warner hired Nathan Levinson to help get the new station licensed and on the air. Levinson was a talented engineer and was director of the Pacific Division of Western Electric, the largest manufacturer of broadcasting equipment. Levinson would later go on to help Warner Brothers Studio become a pioneer in talking motion pictures. Frank Murphy, Warner’s chief electrician and carpenter, was also part of the team that got the station on the air. Additional technical supervision came from Kenneth G. Ormison, who was the well-respected chief engineer of Aimee Semple McPherson’s KFSG, and later was chief engineer for Los Angeles-Hollywood stations KEJK/KMPC, KMTR and KNX. In 1934, he helped boost the latter station’s power to 50,000 watts. SHOULD WE CALL IT KWBC OR KFWB? On February 12, 1925, the Los Angeles Times ran the headline “NEW RADIO STATION FOR HOLLYWOOD,” to announce the new station. But the call letters in the story were not KFWB! The article said in part: Radioland will be

able to tune

in on a new broadcasting station beginning March 4, next. It will be

station KWBC, now being installed at the Warner Brothers studio on

Sunset Blvd. at a cost of $50,000.

The article added, The

station, named with the last three letters, representing Warner

Brothers’ Classics, will not be a commercial proposition, nor will it

be used for the exploitation of Warner Brothers pictures, Sam Warner

said yesterday.

However, KFWB soon became a commercial station and often promoted Warner Brothers movies, along with its actors and actresses. For unknown reasons, Warner Brothers Studio soon decided not to use the call letters KWBC, which were only publicized in that newspaper story. Their new station was to be known as KFWB, a sequentially-assigned set of call letters that the Department of Commerce listed in its Radio Service Bulletin of March 2, 1925. The call letters were given to Warner Brothers following KFWA in Utah and before KFWC in Upland, CA. The letters W and B for Warner Brothers were part of the call sign, but may not have been specifically requested. Nonetheless, Jack Warner joked over the years that KFWB stood for “Keep Filming, Warner Brothers,” while another story claimed the calls stood for “Keep Fighting, Warner Brothers.” The FWB may also have referred to the “Four Warner Brothers.” In my research, any such slogan using the letters of KFWB never appeared in any of the popular radio magazines or newspapers of the 1920s; but, did I discover two KFWB advertisements during World War II in the 1943 and 1944 Radio Annuals, with the adopted slogan “Keep Fighting With Bonds.” KFWB’S OPENING NIGHT The Sunday, March 1, 1925 issue of the Los Angeles Times announced the opening of the new station that week: Wednesday

night (March 4) at 7 p.m., another radio broadcasting station takes its

place among the stations of Los Angeles. From the towers which have

been erected upon the grounds of the Warner Brothers studio on Sunset

Boulevard will flash the call letters KFWB -- Warner Brothers, who are

owners of the studio, promise a number of novelties for the opening

night. KHJ, The Times, extends its best wishes for the success of this

new undertaking.

When 7:00 p.m. arrived on the night of March 4, the first voice heard on KFWB’s first broadcast was Warner Brothers actor and movie colony favorite Monte Blue (1887-1963). Charlie Wellman was the station’s first announcer. Also that night, KFWB did the first of many remote broadcasts from the Montmartre Café on Hollywood Blvd. at Highland, one of Hollywood’s first successful nightclubs. With KFWB now on the air, one purpose of the station during its first year or two was to promote and advertise movies made by Warner Brothers. One early gimmick to attract radio listeners was to place a microphone on various movie sets, so those at home listening to KFWB could “hear” motion pictures being made as they were filmed. The listeners-in heard the director’s commands given to the actors and crew, the mood music being played for the silent actors, the whir of the camera, etc. Some movie studios feared that radio broadcasting would keep people at home and away from the theaters, but the Warner Brothers believed radio could help their studio. They played up the glamour of Hollywood and the movies on their new station. This is evident in KFWB’s early slogan in the 1920s: “Movieland-Lights, Camera, Action”, which was heard at the beginning of the KFWB broadcasts in the station’s earliest years. Famous and not so famous Warner Brothers actors and actresses took turns as guest announcers for the station during the 1920s into the 1940s. EARLY DAYS OF COMMERCIALS On March 25, 1925, only three weeks after KFWB's debut, Variety ran a story about radio advertising in the major U.S. cities, including Los Angeles. The item began: With the addition of

station

KFWB, indications are that a war will be carried on in Los Angeles for

radio advertising business. This latter station is owned and operated

by Warner Brothers, picture producers. It began a campaign to get

business from the other three commercial stations, KFI, KHJ and KNX.

Depending on the program, KFWB was asking $50 to $150 an hour for air time ($680 to $2,040 in 2015). Commercial speakers were asked to pay $50 for ten minutes. And the remote broadcast each night from the Montmarte Café saw the restaurant/nightclub paying Warner Brothers $250 ($3,378 in 2015) for the air time from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m. KFWB already had several other sponsors signed, including a coffee company, a hotel, and a mattress company. KFWB also offered the other movie studios free use of KFWB to broadcast for one hour. By the summer, KFWB was airing a weekly talk from a real estate company selling homes and land near Mulholland Drive. AN EARLY RADIO CONTEST Radio station contests were in their early stages in 1925, in an effort to attract interest in radio and new listeners. KHJ had just held a drawing to give away a new Stewart-Warner radio, with over 30,000 entries sent to the station! So, KFWB did the same thing in September of 1925 on the Monday evening “Radio Doings Technical Hour”, hosted by the magazine’s technical editor and KFSG engineer, Kenneth G. Ormiston. Listeners had to send in a 300-word letter on the topic “Why I Would Not Be without a Radio Set”. Letters were read over KFWB each week on the show and at the end of 30 days, the best letter, as decided by the judges, would win a Valley Tone radio worth either $125 or $184 (equal to $1702 and $2,505 in 2015). The radios came complete with batteries, tubes and loudspeaker. KFWB REMOTE STUDIO MAKES CROSS-COUNTRY TOUR Along with Frank Murphy of Warner Brothers, one of KFWB's early engineers was Ben McGlashan, who also played the part of “Big Brother” on the KFWB “Children’s Hour” program. In 1926, Frank Murphy and his KFWB engineers, converted a Moreland passenger bus into a mobile studio that could send remote broadcasts back to KFWB via shortwave. On May 3, 1926, the bus began a road trip across the United States. Its purpose was to stop at various Warner Brothers theaters across the United States and demonstrate how radio broadcasting works. The portable station had the call sign 6XBR and had a transmitter power of 250 watts on either 105 meters or 40 meters. KFWB engineers Ben McGlashan and Calvin Smith were in charge of the portable radio station's broadcasts each night. (McGlashan and Smith left KFWB in January of 1927 to start their own Los Angeles radio station, KGFJ. Smith was later station manager at KFAC for about 30 years, while McGlashan owned KGFJ until 1964.) In its October 2, 1926 edition, the Harrisburg, PA Evening News described how 6XBR and its KFWB staff hosted a three-hour entertainment program outside the Broad Street Theater. A local orchestra, singers and musicians took part in the show. The article said, “Each night at 9 o’clock, the station must be stopped in its tour, no matter where it is, in order to communicate with Station KFWB at Hollywood. Prizes amounting to $1200 are being offered by Warner Brothers to the amateur operators who send in the best reports of this nightly broadcasting.” KFWB’S FIRST ANNOUNCER WAS AN EARLY MOVIE PREMIERE EMCEE Earlier, I briefly mentioned that KFWB’s popular announcer in 1925 and 1926 was Charlie Wellman (1891-1944). He was a singing announcer who came from KYW in Chicago in 1922 and moved to KHJ in Los Angeles starting in 1923. He was also a singer who recorded for Brunswick Records, and so he often sang on the air. Wellman would keep listeners from tuning to another station by saying, “Don’t go away folks, don’t go away!” This soon became a popular catch phrase of Southern California radio fans at the time. After two highly successful years on KFWB, Charlie Wellman took an announcing job with KMIC in Inglewood; this lasted only two months and then was heard on KGFJ at the end of 1927. He returned to KHJ by 1928, when he was known as “The Prince of Pep”. By early 1926 Wellman was doing double-duty as both KFWB’s station manager and on-air announcer. In those years, it was common practice for stations to hire announcers who could also sing. The idea was for the announcers to fill airtime with a song or two, in case another scheduled singer or musician failed to show up for the broadcast. Don Wilson and Harry von Zell are two other examples of singing radio announcers heard in Los Angeles. Later, Charlie Wellman became more of a singer on numerous Los Angeles radio shows and was less known for his announcing. KFWB also had its own theme song in 1925-’26! A Radio Digest story of November 14, 1925 reported that Charlie Wellman wrote and sang it, at the beginning of KFWB's broadcast every night. While we don’t know the music to this song, the long-forgotten lyrics go like this: If you want to hear a

station, don’t go away folks, don’t go away!

Just turn your dial and wait a while, we’ll be on the air to stay. We will try to make you happy, from Hollywood to Tennessee, From Warner Brothers Studio, K-F-W-B! Wellman seemed to be the perfect host for the nightly Warner Brothers Frolic program over KFWB, where Warner's contract players were often heard. A 1936 Los Angeles Times story on Wellman’s radio career claimed he was also the first person to broadcast a Hollywood movie premiere. On August 20, 1926, Wellman was the emcee for KFWB’s one-hour broadcast from Grauman’s Egyptian Theater for the premiere of the Warner Brothers film “Don Juan”, starring John Barrymore. (Whether or not it was actually the first movie premiere ceremony heard on radio is unconfirmed.) He regularly interviewed and introduced the studio's actors and actresses on the "Warner Brothers Frolic" programs in 1925 and 1926, where movie fans could hear their favorite screen personalities sing and entertain, or simply take their turn as KFWB announcer for the night. Wellman worked at other Los Angeles stations into the late-1930s, including KTM, KFI-KECA and KFAC. When Charlie Wellman left KFWB in 1927, Bill Ray was the primary announcer heard on KFWB hosting the Warner Brothers movie premieres from about 1928 into the 1930s. One of the unannounced guests who played announcer and emcee for a short time was the head of the studio, Jack Warner. In the earliest days of KFWB, Warner, who was himself a big radio fan, played the part of announcer and singer “Leon Zuardo,” the name Warner had used in vaudeville. According to Hal Wallis, Zuardo would croon in the style of his idol, Al Jolson, and tell jokes to the Warner employees sitting in the studio bleachers. Wallis recalled years later that Warner was awful, but he and his co-workers applauded enthusiastically for their studio boss. In Jack Warner’s mid-1960s autobiography, he mentioned his KFWB “Leon Zuardo” performances briefly, but wrote that he retired Zuardo “after KFWB got off the ground.” SOME EARLY KFWB FEATURES The decade of the 1920's was America's “Jazz Age”, and in 1926 many broadcasts featured Frances St. George, the “KFWB Jazzmania Girl”. By January of 1927 she was joined on the “Warner Brothers Frolic” shows by Harry G. Keiper and his Movieland Orchestra. At this time, the new KFWB station manager was Gerald L. King (1899-1976), who was with the station well into the 1930s. William Ray (1898-1970) was assistant manager, and by mid-1927 he was also the station’s main announcer, going by the name of Bill Ray. He had his own Sunday night show called “Ragtime Revue.” In May of 1930, Bill Ray left KFWB to work as the station manager and chief announcer at KGER in Long Beach, but he returned to KFWB by 1934. It should also be noted that Warner Brothers used King and Ray in a few movies, playing -- what else? --- radio announcers! Gerald King appeared as an announcer in the Warner Brothers film “The Time, the Place and the Girl” in 1929. Bill Ray was cast as an announcer in three movies -- “The Secret Bride” in 1934, and in “Poor Little Rich Girl” and “Two Against the World,” both from 1936. At this time, more and more sponsored shows were being heard on KFWB, along with several evening remote broadcasts from hotel orchestras, and the regular broadcasts from the Montmartre Café. By 1928 and 1929, KFWB had expanded its broadcast hours greatly, including live sporting events such as the Pacific Coast League minor league baseball games during the afternoon from Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, and Olympic Auditorium boxing. A January 1931 Radio Doings article said the KFWB manager Gerald King was also a sports announcer, known for his vivid descriptions of football and baseball games over KFWB. He was responsible for bringing the football and baseball broadcasts to the station. A 1934 schedule showed that KFWB was broadcasting the day baseball games, while the night games from the same ballpark were heard over KFAC. (The Angels games moved briefly to KMTR in 1932.) The Boswell Sisters, a popular vocal trio of the early Depression years, were featured on KFWB in 1929 and 1930, before they had network shows of their own on NBC and CBS and were recording with Bing Crosby. KFWB HELPS CAPTURE A MURDER SUSPECT In February of 1928, KFWB got national praise from Radio Digest magazine. The Warner Brothers station was credited for helping to capture a man in Oregon who had kidnapped and murdered a young girl. KFWB station manager Gerald King, announcer Bill Ray, and chief engineer Frank Murphy were at the microphone for 18 hours, helping police and the public to recognize and capture the fugitive killer, Edward Hickman. They also used KFWB to raise the reward money to capture him. The article called the KFWB broadcast “the most amazing story of radio service in appeal and response on record.” The mayor of Los Angeles and the Police Department’s Chief of Detectives also thanked KFWB for its service in helping with the capture. KFWB’S SIGNAL HEARD FAR FROM HOLLYWOOD During the 1920s and ’30s, KFWB’s nighttime signal was sought by an unknown number of distant radio hobbyists. After sunset, the ionosphere reflects AM signals and sends them hundreds and sometimes thousands of miles away from the station’s antenna. Of course, the condition of the ionosphere changes from night to night. A far away station could come in loud and clear one night with little noise or fading, and the next night, a DX'er might not hear anything on the same frequency. With less than 700 radio stations on the air before 1927 and much less man-made noise on the AM band than exists today, East Coast DXers with a well-made radio and a good antenna could tune in out-of-state stations, even from California if reception conditions were good. Only a year after KFWB went on the air, it was receiving reports of being heard on the east coast. A newspaper in Huntington, New York on Long Island printed a column for DXers in 1926. In one of those columns from August 1926, it was reported that a DXer in that city heard KFWB in Hollywood one night and received a letter of verification. The letter was printed in the newspaper and this is what was in the letter: “Your letter of recent date received and this is to confirm your reception of Warner Brothers radio station KFWB. You certainly stepped out some distance when you received our station, considering weather conditions, etc. and your letter was very interesting to us. (Signed), Charlie Wellman, Manager and Announcer of KFWB.” The columnist added, “Better proof of the reception could not be wanted, and we hope those skeptical (radio) fans around Huntington who think reception of California stations in summer is impossible, will read this letter carefully.” Another radio fan in that same area trying to hear out-of-state radio stations also logged KFWB in July of 1926, according to the same DX column in that city’s newspaper. The DX fan named Bob Angel heard the 500-watt station from Hollywood late at night and heard the faint station ID after a piano solo. The static interference was only slight. KFWB was heard again during the summer months on Long Island, New York in 1928. Back in 1991, a veteran DXer named Eugene Martin of Denver, Colorado sent me a list from his radio logbook from 1928, when he lived in Dallas, Texas. Martin said he logged 22 stations from the Los Angeles area that winter and 500-watt KFWB was heard more than once. By 1933, when KFWB was operating with 1,000 watts from its Hollywood Blvd. antenna at the Warner Brothers Theater, a distant listener in Oakhurst, New Jersey, sent KFWB a signal report. John Tweedie received a letter verifying his reception report of KFWB from station manager Gerald King. (See the copy of the letter in the sidebar.) At that time, there were only three other radio stations on 950 kilohertz with KFWB. Theywere WRC in Washington, D.C.; KMBC in Kansas City, Missouri; and KGHL in Billings, Montana. Those stations were off the air by 1:00 a.m. Eastern Time, which left the frequency clear for east coast DXers to try to hear KFWB. KFWB did not go off the air for another 2½ hours, at 12:30 a.m. Pacific Time; that is, 3:30 a.m. Eastern Time. From 1933, when there were 599 radio stations in the United States, let's jump ahead to 1937, when 646 stations were on the air. KFWB was still getting a lot of reception reports from far-away listeners. Like many other stations, KFWB began using a pre-printed QSL card to save the chief engineer time, so he could fill in the date and time the DXer heard KFWB. Such a card was sent to Peter Clarius of Staten Island, New York. He logged KFWB on March 7, 1937 at 3:46 a.m. Eastern Time, just 14 minutes before KFWB went off the air for the night. Two years later, a similar card was sent to Norman McGuire in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania for his reception of KFWB on March 4, 1939 at 2:38 a.m. E.S.T. At that time, KFWB was using 5,000 watts of power during the day, but only 1,000 watts at night. There were 722 radio stations in the United States that year. By 1946, KFWB had increased its night power to 5,000 watts, when the station’s signal was heard by radio hobbyist Robert S. Knox of Newton, New Jersey. The station had moved to 980 on the AM dial by 1946, and the change in frequency is shown on this QSL card. White’s Radio Log, in the fall of 1946, showed 7 other stations on 980 kilohertz besides KFWB, including two in Canada. Knox picked up the KFWB signal on his radio at 3:30 a.m. Eastern Time, 30 minutes before KFWB’s 1:00 a.m. Pacific/4:00 a.m. Eastern Time sign-off. A November 20, 1955 KFWB QSL card sent to Roy Millar in Issaquah, Washington, is interesting because the verification card still shows that KFWB was owned by Warner Brothers, even though the movie studio had sold the station in 1950. Perhaps the engineer wanted to use up all the old QSL cards. Note that KFWB was on the air 24 hours daily by the time of this 2:00 a.m. Pacific Time reception. By this time, there were 22 U.S. stations on 980 kHz, though some of these were daytime-only broadcasters. MORE TECHNICAL CHANGES After only four years of use, the highly-visible KFWB transmitting antenna in front of the Warner Brothers Studio on Sunset Blvd. was being decomissioned. On March 4, 1929, the station’s fourth anniversary, KFWB moved its transmitter and antenna to the top of the Warner Brothers Theatre building (later known as the Pacific Theater Building) at 6425 Hollywood Blvd. While trying to make early sound movies at the Sunset Boulevard lot, the audio from the KFWB transmitter kept bleeding into the soundtracks of the movies being filmed. So, the engineering department decided it was best to move the transmitter away from the movie sets. KFWB's studios were also gradually moved to the Hollywood Boulevard site. (In 1937, KFWB’s transmitting site was moved from the roof of the Warner Theater Building in Hollywood to the Baldwin Hills area on La Cienega Blvd., south of where KABC is today. Here, for the first time, the station used a vertical radiator, the type of AM tower or antenna that we’re familiar with today, which sent out a more reliable signal over the L.A. Basin. Then, in the late 1950's, KFWB moved to its present location, a 3-tower site in East Los Angeles near the 5/10-freeway interchange, which is shared with KLAC-570.) The date of KFWB’s fourth anniversary in 1929, March 4, also marked the beginning of a monthly coast-to-coast network broadcast which originated in the KFWB studios and traveled east over the stations of the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS). Famous names from stage and screen were heard on this program, along with outstanding musical talent of Southern California. Some of the featured performers on that inaugural CBS national broadcast included Al Jolson, Monte Blue, Conrad Nagel, and Earl Burtnett’s Biltmore orchestra. The monthly network programs from KFWB over CBS were heard as a part of the regular Vitaphone Jubilee Hour. KFWB and KMTR carried several CBS network programs in Los Angeles in 1928 and 1929. But then, in July of 1929, CBS announced that KHJ would be the network’s permanent Los Angeles affiliate, a relationship which began on January 1, 1930. In the October 12, 1929, issue of Radio Doings, KFWB promoted the fact that the Warner Brothers Studios had bought First National Pictures in Burbank and that the movie studio would be soon moving to that movie lot. For example, on Monday nights at 9 p.m., KFWB listeners heard “The First National Hour”, which featured Leo Forbstein and his Vitaphone Recording Orchestra, along with First National stars and players. The station also featured the KFWB Concert Orchestra, music from the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood, a mystery serial called “Who Killed the Caretaker”, USC football from the Coliseum (also carried by several other L.A. stations), and on Sunday mornings at 8:30 a.m., "The Funny Paper Man". Comedian Jack Benny made one of his earliest, if not his first radio broadcast, over KFWB on the night of April 26, 1930. This was the National Vaudeville Association Benefit Show, broadcast from the Shrine Auditorium and sponsored by MJB Coffee. Radio drama was gaining in popularity during the early 1930s, and by 1932, KFWB was one of five stations in L.A. using paid dramatic actors on its local programs. From 1932 to 1935, a KFWB producer/writer/actress named Kay Van Riper presented dramatic programs such as “English Coronets” and “American Caravan”. One of her regular actors was Gale Gordon, who later went on to act on many network radio shows, and was best known in later years on television in “Our Miss Brooks” and “The Lucy Show”, plus many other guest roles on various shows. THE DEPRESSION CAUSES MONEY TROUBLES The radio industry was not immune from being hit hard by the Depression in the early 1930s. In the October 15, 1931, issue of Broadcasting, the magazine reported that “KFWB, Hollywood, a year ago showed a $12,000 deficit during the summer season. This year it is reported as having come out of the red and made a small margin of profit besides. Warner Bros., owners, imposed a 25 per cent salary cut early in the summer.” By contrast, in some of my earlier research, I discovered that radio station KFOX in Long Beach also had employees take pay cuts around 1932-33 and that KFAC-Los Angeles operated at a small loss in 1934, but showed a profit of $568 during the first nine months of 1935. FOUR MORE FILM STUDIOS BRIEFLY AFFILIATE WITH RADIO STATIONS By mid-June of 1931, a total of five Hollywood movie studios were hooked up with a radio station to promote their films. KFWB was still the only radio station to be owned and operated by a movie studio in the film capitol, but the June 16, 1931, issue of Variety reported that KMCS-1120 in Inglewood had made a deal with Metropolitan-Christie Studio to promote its comedy films. The deal was short-lived and by January of 1932, KMCS moved to downtown Los Angeles’ Arcade Building on Spring Street and became KRKD (known today as KEIB-1150). Variety added that other radio stations to be directly affiliated with a movie studio included KMTR (now KLAC-570) which had recently relocated to the United Artists movie studio; KFVD (now KTNQ-1020), broadcasting from the Hal Roach Studio in Culver City; and KNX, located on the Paramount Studio lot. The article said that while KFWB was promoting Warner Brothers’ movies and local Warner Brothers’ theaters, it was also selling air time to Fox-West Coast each week until KFWB decided it was competition with its own theaters and refused copy, only to retract several days later. An earlier Variety article from January 21, 1931, was similar in nature. It stated that KNX, on the Paramount lot, had an hourly announcement exploiting Paramount’s products. The studio also took about 5 hours a week over KNX to have Paramount stars make personal appearances before the KNX audience. United Artists utilized KMTR in much the same way. Tec Art and Metropolitan studios paid for time at KFOX and KMCS respectively. The article said, “Both studios will hold out the air plugs as bait to independent producers leasing space on the lots.” KNX moved off the Paramount lot in 1933; KFVD had moved off the Hal Roach lot by 1933; and KMTR had moved off the United Artists lot by 1938. KFWB HIRES GROUNDBREAKING DISC JOCKEY AL JARVIS During August of 1934, announcer Al Jarvis started a program on KFWB playing phonograph records, but presented as though he were introducing tunes being played by live bands at dance remotes. Jarvis first tried out this type of record program in 1932 and ’33 at KELW, KFAC, KMTR and KMPC in the Los Angeles market, but Station Manager Gerald King believed that the show would do much better on KFWB, so he hired Jarvis. Al Jarvis called his program “The World's Largest Make-Believe Ballroom”, and it was probably one of the earliest examples on U.S. radio of a disc jockey radio show in which the announcer injected some of his own personality into the program while giving added details about the song and the singer or a certain band and band leader. It was not just the stiff reading of the song title and artist that was so often heard at that time on radio. Since the job title of “disc jockey” did not come into use until the 1940s, local radio columnists called Jarvis “the record man,” “a record spinner,” or a “record commentator.” When KFWB had some trouble selling the record program to advertisers, Jarvis asked station manager Gerald King to find a substitute host, while Al attempted to sell the show himself. Martin Block, who had previously worked a while with Al Jarvis at KMPC, was hired to do the show in Jarvis’ place. Later, Block and Jarvis had a misunderstanding and Block left KFWB. In 1935 Block was hired at WNEW in New York, and started his version of “Make Believe Ballroom”, a concept he had copied from Jarvis. It proved to be quite popular, and it ran for many years on the east coast. But, there is no doubt that Jarvis created the “Make Believe Ballroom” program. Jarvis tried to sue several times to stop Block from using the "Make Believe Ballroom" title for his WNEW programs, but was unable to win his case. In 1959, former KFWB Manager Gerald King wrote a letter to Broadcasting magazine. He stated that it was Al Jarvis who created the Make Believe Ballroom show and not Martin Block, and he told the story how he hired Jarvis in 1934 and later used Block as a temporary substitute host. The complete letter is here. Jarvis hosted the "Make Believe Ballroom" at KFWB into 1937, and then took the show to KMTR-570 (now KLAC). This pioneer disc jockey returned to KFWB from September 1939 until March of 1946, then moved again to KLAC for several years. He came back to KFWB once more in February of 1953 and stayed through the station’s “Color Radio” Top 40 music days in March of 1960, and was back briefly in 1962. MORE RED CARPET ON THE RADIO Hollywood movie premieres had been staples of Los Angeles radio since the 1920s. I mentioned earlier that KFWB’s Charlie Wellman covered a Warner Brothers film premiere in 1926. The opening nights for new movies in Hollywood still had radio listeners tuning in during the 1930s. Most L.A. stations took part in such broadcasts, but KMTR in Hollywood and KFWB, with studios on Hollywood Boulevard at the Warner Brothers Theater, seemed to broadcast the majority of these ceremonies. An example of KFWB promoting a Warner Brothers film is described on the radio page of the Los Angeles Times of August 30, 1934. The brief item said that “the Busby Berkley musical “Dames” will be given its premiere at Warner Brothers Hollywood Theater at 8:30 p.m.” The brief story said “KFWB’s microphones will be installed along the boulevard, on the sidewalks, over the theater lobby, at the entrance of the theater and across the street to pick up the atmosphere, music and color of the occasion. Announcer Bill Ray is to introduce the stars, with the assistance of Al Jolson, Dick Powell, Hugh Herbert and Guy Kibbee.” Jolson, who starred in “The Jazz Singer” in 1927 for Warners, had been a longtime favorite of Jack Warner and had been heard on several KFWB broadcasts since the late 1920's. A 1931 movie premiere on KFWB at the opening of Warner's Wiltern Theater in 1931, and KFWB announcer Bill Ray, who was emcee for most of the WB movie premiere broadcasts in the '30s, can be seen in this clip on YouTube. KFWB MARKS TEN YEARS OF BROADCASTING On the night of March 4, 1935, Warner Brothers took some time out from movie making to celebrate KFWB’s tenth anniversary on the air. Los Angeles Times radio columnist Carroll Nye gave his readers a rundown of plans for the special broadcast: "They’re going to

blow off the

lid at KFWB with an extravaganza beginning at 8:30 p.m., in celebration

of the station’s tenth anniversary. Harry Warner, president of Warner

Brothers, is to be special honor guest, and listeners will hear an

hour-and-a-half show produced and directed by Benny Rubin and Bill Ray.

Frank Murphy, “Daddy of

KFWB,” will introduce Monte Blue, who spoke the first words over the

station at its inaugural broadcast ten years ago today, and a large

company of screen and radio stars will contribute to the entertainment.

Among those billed are the Dudley Chambers Choral Group, Josephine

Hutchinson, George Brent, Kay Francis, Warren Williams, Bette Davis,

Ruth Connelly, Guy Kibbee, Lyle Talbot, Warren and Dubin, tunesmiths;

Phil Regan, Al Jolson, Hugh Herbert, Joan Blondell and Dorothy Dare.”

Warner’s musical star Dick Powell also took part in the KFWB broadcast that night. A feature story in the May 1, 1935 issue of Broadcasting magazine included several photos taken during the KFWB tenth anniversary broadcast at Warner Brothers. To see that article and the photos, click here here and scroll down to page ten. KFWB also placed several ads in Broadcasting during their tenth anniversary year of 1935, featuring several Warner Brothers stars. One featuring Dick Powell is here. OTHER 1930's HIGHLIGHTS Another 1930's favorite, which became very popular on KFWB, was a program featuring the western singing group “The Sons of the Pioneers.” Gerald King got them to appear on KFWB in 1934. One of the singers in the group was Leonard Slye, who became better known in western movies as Roy Rogers. The western group was first called “The Pioneer Trio", but KFWB announcer Harry Hall told them that they looked too young to be pioneers, so he said from that moment on they would be known on the air as “The Sons of the Pioneers”; the name stuck. Voice actor Mel Blanc had been a character actor on KGW in Portland, Oregon. He moved south to L.A. and got his first regular radio job in 1937 on the Johnny Murray show on KFWB. This led to Warner Brothers Pictures signing him to his first contract with the movie studio’s cartoon department, where he created the voices of Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig, Daffy Duck and countless others. On August 1, 1936, Gerald King resigned as General Manager of KFWB because of policy differences with Jack L. Warner, head of the Warner Brothers Studio. His replacement was Harry Maizlish, previously a publicity man for the movie studio. Maizlish in turn appointed former KFWB announcer Bill Ray as the new sales manager. Gerald King continued his radio career as the president of Standard Radio Inc., a producer of radio transcription programs. At this same time, new KFWB studios were being built at 5833 Fernwood Avenue near Van Ness in Hollywood, which opened in 1937. This was one block south of Sunset and Bronson, close to where the station began in 1925. In 1936, KFWB was operating with 2,500 watts day and 1,000 watts night, but would soon have a new transmitter site in Baldwin Hills, with a power boost to 5,000 watts. Also, in June of 1937, Al Jarvis left KFWB after three years to take his Make Believe Ballroom show to KMTR-570. He would be back before too long. FUTURE PRESIDENT REAGAN WAS ON KFWB In June of 1937, an Iowa radio announcer and sportscaster was signed by Warner Brothers Studio as a movie actor. A few months earlier, Ronald “Dutch” Reagan had been covering the Chicago Cubs Spring Training on Catalina Island for WHO radio in Des Moines, Iowa. During his time in Southern California, he got Warner Brothers to give him a screen test, and they liked what they saw. In his first film, “Love Is in the Air,” Reagan played the part of a radio announcer. At the end of the year, WHO was getting ready to carry the NBC network feed of the New Year’s Day Rose Bowl football game from Pasadena, California. Just before January 1, 1938, WHO decided not to carry the NBC feed of the game. Instead, they persuaded Warner Brothers to allow their former sportscaster Ronald Reagan to announce the play-by-play of the football match between Alabama and California over KFWB and WHO simultaneously. The special telephone line to carry the game from Pasadena to Des Moines cost WHO more than $1,600 (more than $27,000 in 2015 dollars). The Los Angeles Times radio column from January 1, 1938, said Reagan would be assisted during the game by Jere O’Connor and Manning Ostroff. O’Connor was KFWB’s special events director at the time. Ostroff was on the staff of KFWB as an announcer, producer and writer. He was also a producer for Eddie Cantor’s radio and television programs. Just two months later, when KFWB was covering the heavy rains and flooding in the Los Angeles area, Warner Brothers asked Ronald Reagan to help the station report on this emergency. And in April of 1938, KFWB and several other stations around California and across the United States aired the first episode of a series called Warner Academy Theater. The first radio play was “One Way Passage,” an adaptation of an earlier Warner Brothers movie. Ronald Reagan was the male lead in this radio play over KFWB. To hear this broadcast, click here. 1939 TO 1945 In September of 1939, Variety reported that “Al Jarvis, the creator of Make Believe Ballroom on KFWB five years ago, returns to the Warner station for a five-time weekly broadcast of the feature.” The program was still one hour long, from noon to 1:00 p.m. During the same year, KFWB started broadcasting dramatized versions of historical and current news events of the day. One of these programs, designed to stimulate appreciation of America’s democratic ideals, was “America Marches On,” which featured movie stars from Warner Brothers. Other entertainment shows from the late ’30s on KFWB were "Let's Go Hollywood", “Can You Write A Song?", "Take the Air" and "Amateur Authors". Also in 1939, Frank Bull began a disc jockey record show on KFWB, “America Dances,” which was heard on the station until 1956. Bull was also a sportscaster who hosted another KFWB program, "The Sports Bulls-Eye with Frank Bull". Ronald Reagan’s brother, Neil Reagan, was also a radio announcer and soon moved to Hollywood to work for KFWB. He became the station’s program director by 1944. An aircheck recording exists of KFWB covering the stars arriving for the Academy Awards on March 2, 1944, with Neil Reagan the announcer. The KFWB program lasts 29 minutes. The remaining 24 minutes consists of the CBS West Coast/KNX radio coverage of the Oscar winners that night with Ken Carpenter and Jack Benny. By 1938, KFWB’s chief announcer was Harry Hall and the Station Manager was still Harry Maizlisch. Hall had been on the KFI announcing staff back in 1929. Joe Yocum was KFWB's chief announcer in the 1940's. A popular show then was "Preview Theatre", which turned popular novels into radio plays. A broadcast of that program, starring a young June Lockhart and Freddie Bartholomew, was being broadcast on KFWB when Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941. All of the Los Angeles radio stations were extremely busy and involved in the war effort during World War II. KFWB was no exception. In 2014, it was announced that a transcription disc recorded from the KFWB D-Day broadcast on June 6, 1944, had been found at USC, broken in half, and then restored. On June 8, 2014, a KCAL television news report told the story of the KFWB recording from 1944 and played a few audio clips from the transcription disc. You can hear that report and the KFWB announcer’s D-Day report at this link: HAL STYLES AND THE 1944 CONGRESSIONAL RACE Hal Styles (1895-1975) had been in Los Angeles radio since 1932, and brought his popular program “Help Thy Neighbor” from KHJ to KFWB in 1940. He stayed at the Warner Brothers station into the late 1940's. “Help Thy Neighbor” began as a way to find jobs for the unemployed in Southern California, but later evolved into other ways of helping people. In seven years, the program was credited with finding jobs for 35,000 people. By late July, 1944, Styles was hosting another show for KFWB, “Good Samaritan of the Airways.” After that show went off the air, he was still heard on KFWB hosting three other programs that same year. Those were “Hal Styles’ Scrapbook of Life,” which aired Monday through Friday; “Young America Speaks” on Saturdays and “Lest Ye Forget” on Sundays. In 1944, Styles ran for Congress as a Democrat in the Hollywood district of Los Angeles. KFWB Station Manager Harry Maizlish conceived of running Styles for Congress, and he also managed Styles’ campaign against the Democratic incumbent Joseph M. Costello. Costello had been criticizing some motion picture people (KFWB was owned by Warner Brothers Studio), and they felt they needed a new congressman. Styles won the primary election to defeat Costello, but reporters learned that Styles had been a leader of the Ku Klux Klan in New York State in 1926. Styles admitted joining the Klan but said he had resigned in 1930. He then wrote a series of newspaper articles, which harshly criticized the organization. But the voters didn’t buy his explanation, and in the November general election, Styles lost to the Republican nominee, Gordon McDonough, by 26,605 votes. It was Styles’ one and only time running for public office. By 1945, Hal Styles had started a radio broadcasting school in Beverly Hills. He also hosted an audience participation show on KFWB during 1945 and ’46, “So You’d Like to be in Radio.” It was a scripted show with guest stars and radio actors. Each week, a winner was awarded a scholarship to the Hal Styles School of Radio. The radio school lasted into the early 1950s. Hal Styles left radio and did “Help Thy Neighbor” on television for a few years. By 1956, he became a minister founded a non-denominational church in Reseda. He led that church until his death in 1975. While at KMTR and KHJ in the 1930s, Hal Styles was billed as the world’s fastest-talking announcer, able to speak at a rate of 450 words per minute. He won a radio diction contest in 1928 and was once competed over the air on KFI against KFI and KECA announcers who tried to keep up with his rapid-fire style. AL JARVIS LEAVES KFWB, STATION HIRES MARTIN BLOCK In March of 1946, seven years after returning to KFWB from KMTR, Al Jarvis quit his show at KFWB and took "Make Believe Ballroom" back to KLAC-570 in Hollywood (the call change from KMTR took effect March 7th). His new salary for the KLAC job was reportedly $250,000 or $3.2 million in 2014 dollars. The story on his move from KFWB to KLAC appeared in Variety on March 6, 1946. Another story on March 1, 1946 in Variety stated that Jarvis had just celebrated the 14th anniversary of his "Make Believe Ballroom" show, meaning that the program had started in 1932, likely while Jarvis was still on the air at KELW in Burbank. During 1947, with Al Jarvis’ "Make Believe Ballroom" on KLAC at noon Monday through Friday, KFWB hired Martin Block to do his version of the show at the same time as Jarvis’ show. In the July 18, 1947 issue of Variety, it was reported that “Hooper Rating KLAC ordered on rival KFWB’s Martin Block and its own Al Jarvis over the month of June, shows Jarvis to be leading by one point. He has figure of 6.2 and newcomer Block holds 5.2, according to the report submitted.” The story said “since Jarvis has been familiar to Southern California radio listeners since at least 1933, it is likely one of the reasons Jarvis has the slight edge over Block in the ratings battle.” Block had been on the air in Los Angeles only one month, after leaving WNEW-New York. Block, who had worked with Jarvis at KMPC and KFWB in 1934 before taking Jarvis’ idea for "Make Believe Ballroom" to New York in 1935, was recording a version of the show to be played back in New York on WNEW after his arrival at KFWB. Soon after Block’s June, 1947, arrival in Hollywood, KLAC and KFWB decided to give Southern California music fans three hours of Jarvis and Block from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., Monday through Friday. But the hype that surrounded Martin Block’s arrival on the Los Angeles airwaves to compete against Al Jarvis in the battle of the disc jockeys, ended all too quickly. Both Broadcasting and Variety reported during the first week of October 1947 that Martin Block had severed relations with KFWB by mutual consent, after fulfilling only four months of his three-year contract. In doing so, Block agreed not to appear on any Los Angeles station before June 1, 1950, the end date of the contract. KFWB asked to be released from its obligation to the Mutual Broadcasting System, which was taking Block’s shows from KFWB for a network broadcast. However, Block continued to broadcast over the Mutual network from KHJ in Hollywood. WARNER BROTHERS SELL KFWB AFTER 25 YEARS By 1950, KFWB had changed its programming to include mostly news, sports and popular music, with disc jockeys playing the latest hit records. In October of 1950, Warner Brothers decided to sell KFWB. Broadcasting magazine reported in its issue of October 2, 1950 that the FCC had approved the movie studio’s $350,000 sale of KFWB to a new firm, headed and controlled by the station’s General Manager, Harry Maizlish. The sale price would equal roughly $3.5 million in 2015. Maizlish had been KFWB’s station manager since 1936. In September of 1956, Maizlish sold KFWB to Crowell-Collier Broadcasting for $2.35 million (equivalent of $20.5 million in 2015). A RUNDOWN OF POST-WARNER BROTHERS PROGRAMMING On January 2, 1958, KFWB became L.A.’s first full-time Top 40 rock and roll station under Program Director Chuck Blore. An enormous line-up of talented radio personalities entertained listeners with the “Color Radio” format for several years and made the station number one in the ratings. The long list of DJ's on this station has been highlighted many times over the years. To name just a few, it started with the original air personalities who were called the “Seven Swinging Gentlemen” (Bruce Hayes, Al Jarvis, Joe Yocam, Elliot Field, B. Mitchell Reed, Bill Ballance and Ted Quillin). Al Jarvis had been playing records on KFWB on-and-off since 1934, starting with his popular “Make Believe Ballroom” show. Chuck Blore wanted Jarvis to be part of his Color Radio KFWB line-up of air personalities, but Jarvis was not a big fan of the Top 40 music format or rock and roll. Jarvis told Blore, “That’s like asking Picasso to paint a house.” But Blore persisted and Jarvis came through for KFWB from 1958 until March of 1960. In fact, Blore said that during those years, KFWB-Channel 98 in Los Angeles averaged a 34 share rating, but Al Jarvis had the highest rating of all the KFWB disc jockeys, with a 42 share! The next closest radio station in the ratings was KMPC with an 8.8. The Top 40 format continued at KFWB with other personalities such as Gene Weed, Gary Owens, Jim Hawthorne, Sam Riddle, Jimmy O’Neill, Roger Christian, Wink Martindale, Larry McCormick and at the end of its music years, the team of Al Lohman and Roger Barkley. In 1966, Group W (Westinghouse) bought KFWB, and on March 11, 1968, the station dropped its Top-40 music format and changed the its programming to all-news. For many years, Southern California listeners of KFWB heard the familiar slogan, “You give us 22 minutes, we’ll give you the world.” After 80 years in Hollywood, KFWB moved from its Yucca Street studios on June 24, 2005. (On August 11, 2005, KFWB’s all-news rival, KNX, became the last radio station to move from Hollywood.) KNX and KFWB, co-owned by Infinity Broadcasting at the time, moved into a high-rise building at 5670 Wilshire Blvd., southwest of Hollywood. Three co-owned FM stations, KLSX at 97.1, KTWV-94.7 and KRTH-101.1, also occupied this building. After Viacom split from CBS in 2005, Infinity changed its name to CBS Radio. Beginning in 2008, KNX and KFWB were jointly branded as CBSNewsRadioLA. The CBSNewsRadioLA brand was used for simulcasted special programming and for marketing to advertisers. In addition, there were no longer separate field reporters for KNX and KFWB, and CBSNewsRadioLA reporters filed stories for both stations. On September 8, 2009, KFWB debuted a news-talk format, adding several syndicated talk shows to its programming. On November 2, 2011, CBS Radio placed KFWB into a trust headed by Diane Sutter, under the name The KFWB Asset Trust. The was due to CBS Corporation’s ownership limitations after it had bought KCAL-TV nine years earlier. On September 22, 2014, KFWB changed formats to become an all-sports station, calling itself “The Beast 980.” This format lasted until March 1, 2016, when KFWB briefly became "Desi 980", broadcasting a South Asian Bollywood format. Finally, on October 31, 2016, the station was sold to Lotus Communications, and it adopted a regional Mexican format as "La Mera Mera 980". SOME FINAL THOUGHTS There’s no doubt that entertainment history was made 90 years ago when the Warner Brothers studio got into the radio business and put KFWB on the air on March 4, 1925. Motion pictures and radio joined forces to promote the Warner Brothers brand and the station was only a step away from the transition from silent movies to "talkies". In between, there was a lot of air time and history that was made at the Warner Brothers radio station, KFWB. Studio boss Jack Warner (1892-1978) was quoted in Radio Digest magazine in November of 1925, only 8 months after KFWB began broadcasting. Warner had this to say about radio and the movies: There are some who

think that

in attaching a radio station to our picture studio, we are fighting our

own interests and creating a formidable opponent for ourselves. We

believe the contrary to be the case and are confident we are increasing

the number of our friends and patrons, for the entertainment we nightly

broadcast places us in more intimate contact with the public and

increases the friendly feeling they have for Warner Brothers. We are

using radio as it is today – not what it will be tomorrow, although I

confidently expect that in time, the radio and the picture business

must join forces permanently to produce a superior type of

entertainment that will combine all the elements of the stage, the

screen and radio.

The late Gary Franklin was a reporter for all-news KFWB between 1972 and 1980. In 2002, he told this story to LARADIO.com about a time he ran into Jack Warner at an event he was covering for KFWB: “During my early years with KFWB, the early 1970's, I would often run into Jack Warner at premieres and such. I guess he was getting on in years ... but whenever he spotted me, he'd point at the KFWB logo on my over-the-shoulder Sony ... and say, "You know what that stands for? Kinda Funny Warner Brothers ... I used to own you guys." Yes, Jack, you certainly did own KFWB for 25 years. I hope you enjoyed my look at the Warner Brothers’ years of KFWB ownership and remembering KFWB’s pioneer days 90 years ago. Jim Hilliker Monterey December 3, 2015 LINKS: KFWB Switching to All-Sports Format as AM Raio Fights for Survival, Los Angeles Times, Sept. 2, 2014

|