REMEMBERING KPPC-AM:

THE BIRTH AND DEATH OF A HERITAGE RADIO STATION

By Jim Hilliker, © 2006

www.theradiohistorian.org

Copyright

2006 by Jim Hilliker

Jim Hilliker, author

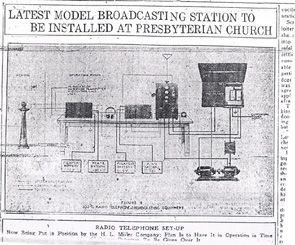

Today, it’s taken for granted how a radio microphone works,

but in 1924 just about every aspect of a broadcasting station was still

new to most of the public. The newspaper story detailed some of the

station equipment this way: “The speech input equipment consists of

Western Electric high quality, distant talking microphones, input

amplifier, control apparatus and batteries. The microphone is mounted

on a casing, which minimizes the effect of mechanical vibration, which

might affect the clarity of reproduced sounds. It may be operated by

talking “close up” or from a distance of several feet. Provision is

also made for adjusting the degree of amplification.”

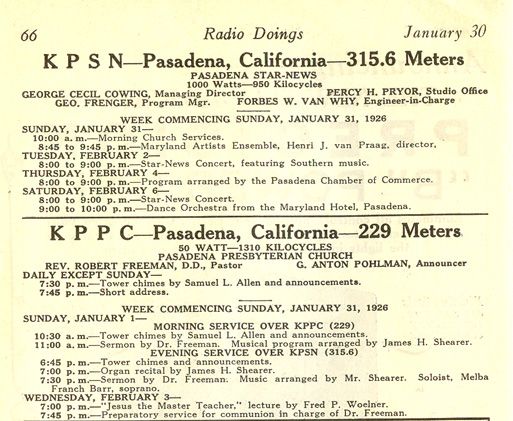

KPPC program schedule, 1926

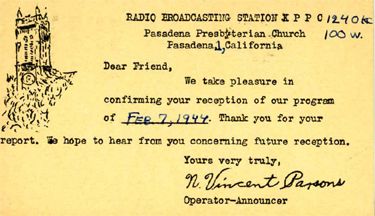

This

is a QSL card mailed to a radio hobbyist in Illinois in 1944 for a

correct reception report, verifying that this person heard KPPC radio

outside the station's regular coverage area. The card was likely

designed by chief engineer N. Vincent Parsons and was used by the

station in the 1930s and '40s.

KPPC transmitter in 1934 (click to enlarge)

KPPC power increase -

Pasadena Post 5/13/1936

(click to enlarge)

Pasadena Presbyterian Church,

from a period postcard.

(click to enlarge)

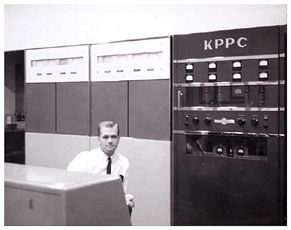

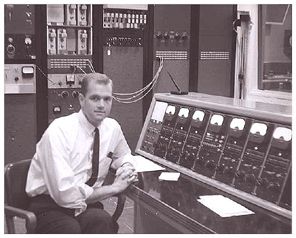

“This picture shows the control booth for KPPC Studio A. This booth was about 6'x15' and faced the actual studio, about 15'x30', a not-squared room on the other side of the slanted double-glass window in front of me. "Not-squared" meaning none of the walls exactly parallel-facing each other, so as to prevent sound reverberation! The studios each had a grand piano, large table, water pitcher, and several floor-standing boom microphones, mostly RCA 77-DX's. Studio B was smaller.

“Behind me (left of this picture) is another slanted double-glass window to Master Control, about 15'x20' which looked like the control console set in Star Trek. The seated on-duty transmitter engineer had the Collins 100-watt transmitter free-standing behind him and the Master Control Console in front of him. To his right were two cabinet-standing Ampex 300's. The wall to his left was entirely built-in equipment racks filled with amplifiers, routers, monitors, meters and patch bays. He could switch or route any audio source in the station plus remote microphones upstairs in the church itself. KPPC and Master Control was in the basement of the Pasadena Presbyterian Church, and had a remote mixing booth in the steeple for the church bells and choir concerts.”

(Photo: Bill Kingman)

The antenna towers for KPSN/KPPC atop the Star-News Building were Pasadena landmarks since late-1925. But the towers never had the KPPC call letters on them. Mike Callaghan grew up in Pasadena and recalls that when he was young, he often rode his bike past the Star-News, thinking the towers were shortwave antennas used by the paper to gather news stories from distant places. Mike also explained that the city used to have two newspapers. “The Southern tower bore the neon for the Star-News and the North one had the Independent. The ‘STAR-NEWS’ was all in block letters, and the ‘Independent’ was in upper and lower case.

- Licensed: December 1924

- First broadcast: December 25, 1924

- Last broadcast: September 1, 1996.

- On the air roughly 71 years and 8 months.

- License deleted: July 11, 1997

For those who were expecting a major article on the groundbreaking “underground” KPPC/fm of the late-1960s, you may be disappointed, but that station does play a part in this story. However, I focus mostly on the AM station. It is by no means the complete story of KPPC-AM, but I hope you like what I have put together here, based on the amount of research I’ve been able to accomplish.

My main goal, in presenting this story, is to explore in-depth the earliest years of KPPC and take a look at what caused it to go off the air. In-between, I hope to show some examples of what the station was like over a span of nearly 72 years. I was hoping to have this ready by Christmas of 2004 for the 80th anniversary of its first broadcast, but am happy to present it now in 2007, 10 years after KPPC-AM went off the air. This may not be as exciting or interesting to some readers as an article on the Boss Radio years at KHJ, KRLA, or the Color Radio days of KFWB, or even articles on KFI or KNX. But, I think the history of KPPC-AM is a unique slice of Los Angeles radio history that may be unknown to many people. In order to preserve that history, I feel it should also be shared by anyone interested in radio history.

AN UNUSUAL RADIO STATION

If you are the owner, station manager or program director of a radio station, how would you like to be told by the FCC that you had to take your station off the air so that another station on your frequency, in a nearby city, could broadcast for a few hours? Or, how would you feel if the FCC told you that in order to allow the other station to go on the air two times a week, you could stay on the air too, but you were forced to reduce your power significantly? For many years, KPPC radio in Pasadena forced these situations on other radio stations in Southern California.

This is the story of a small (by today’s standards) AM radio station in Pasadena, California. KPPC served its city of license for many decades, despite its low power and a very limited and unique broadcast schedule. The call letters stood for its original owner, the Pasadena Presbyterian Church. It was one of the earliest cases in which a radio station owner requested a customized “K” call sign. This was out of the sequential order of call letters that were assigned by the Department of Commerce, which began with ‘KF_ _’ in the western United States in 1924.

In the “childhood short pants” days of radio broadcasting between 1922 and 1930, there were many AM stations owned by churches, but most were eventually sold. KPPC outlasted most of the other early AM stationsDon McCulloch in that category. In the mid-1920s, it also was normal for most stations to use only 10 to 1,000 watts to be heard and be on the air just a few hours per day. But, in later years, when most of the AM stations around Los Angeles boosted their output power and were on every day, KPPC stuck to low power and a twice-a-week schedule, though it was not the station’s choice to be put in that situation. Those circumstances made this AM band survivor a mysterious and possibly a “strange” radio station to other L.A. broadcasters in more modern times. To other people, such as the DX radio hobbyists seeking unusual and low-powered signals to tune-in, KPPC was a rare “catch,” if they could hear its signal, and its call letters were a bit magical and special. In the late-1960s, KPPC became the first AM station with a “free-form underground” rock format, when it simulcasted its sister FM station twice a week. By the 1970s, KPPC was one of the last AM stations in the nation to use only 100 watts of power and one of the last to continue using a wire transmitting antenna, instead of a vertical tower. And, by continuing to serve the public interest and renew its license at renewal time, the FCC allowed KPPC to go on the air just twice-a-week year after year. The FCC also gave KPPC signal protection, by forcing an adjacent channel station and co-channel station to lower their power level whenever KPPC was broadcasting.

In 1989, I received a letter from KPPC program director Bob Gourley, answering my inquiries about the station. The letterhead stated, "Pasadena's First Radio Station Since 1924." That, however, was not exactly accurate. KLB was actually Pasadena’s first station, going on the air in January of 1922, but only lasted one year. KLB appeared to be followed by KDYR, which was to be the Pasadena Star-News' first venture in broadcasting, but there is no evidence that KDYR made even one broadcast. The KDYR license was eventually deleted in December of 1922, apparently without ever having gone on the air. But, until the 1940s, this pioneer broadcaster was the only radio station in Pasadena. Then, starting in 1924, KPPC was the first radio station in Pasadena to take hold in the community and thrive.

During the first few years that radio grabbed the attention of Americans, a new radio station going on the air was quite an event. The beginning of KPPC was no exception. Religious stations had already taken hold in this area of Southern California: KJS at the Bible Institute of Los Angeles had been broadcasting since March of 1922, the first U. S. station using only religious programming on days other than Sunday; Aimee Semple McPherson's KFSG began broadcasting two years later; in February of 1924; and a church in Whittier had obtained a license, KFOC. Another church-owned station, KGEF at Trinity Methodist in Los Angeles was on the air at the end of 1926, but was shut down by the Federal Radio Commission in 1932. All of these radio stations were there to serve their own listeners and were non-commercial. The feeling at that time was that church-owned stations were not in the business of making money.

To give you an idea of how long ago 1924 was, here are a few facts about American life then. In 1924, the population of the United States was 114 million. The average yearly income was $1,124. The median price of a new home was $7,720. The average cost of a new car was $398. A gallon of gasoline cost 21 cents. A quart of milk went for 13 cents, a loaf of bread was 9 cents, a dozen eggs sold for 43 cents and a pound of steak was 41 cents.

In 1924, Pasadena had a population of about 57,000, which would increase to more than 76,000 by 1930. The city boasted of several movie theaters, including the Raymond Theater, the Florence, the Strand, Warners’ Egyptian Theatre, Pasadena Photo-Play, Bard’s Pasadena and the Pasadena Theatre. But the “silent” motion picture was getting some new competition from another modern invention, as a way for Americans to enjoy their leisure time.

Radio broadcasting was still fairly new and evolving in 1924 like the personal computer industry was, not too long ago. Radio was gradually catching on, mainly with men and boys, who tried to convince the rest of the family that it was not a passing fad. The family was then introduced to the music and voices that could be heard over their crystal set headphones or loudspeakers from battery-powered radios with one or more tubes.

In 1924, less than 5% of U.S. households had a radio, but new radio stores kept popping up in most cities and towns, including Pasadena. At that time, Pasadena had a dozen radio stores. By 1925, some 15 businesses in the city were selling “radio apparatus and supplies.” This was an era when many people were still attempting to build their own radios, since completely built radio sets were slow to come down in price. The number of U.S. households with radios increased to 27% by 1928, as the technology, design and ease of operation of radios continued to improve. The cost then gradually came down, which drew more people into buying radios by the end of the decade. And in December of 1924, at the time KPPC got started, ads in magazines and newspapers across the nation were suggesting to consumers that a radio would be a nice Christmas gift for the family.

HOW KPPC BEGAN

Despite some early setbacks, radio broadcasting, which gave people a reason to own a radio, was gaining in popularity in the Los Angeles area by 1924. After several early station failures, stations KNX, KJS, KHJ and KFI had survived and were getting better every day. Three new stations came on the air in 1924, including KFSG, KFON in Long Beach (now KFRN-1280); and KFPG, (now KLAC-570). During the next year, KFWB and KFVD (now KTNQ-1020) also joined the ranks of L.A. area broadcasters. Radio fans in Southern California were excited about the increased number of stations and program choices they would be able to hear.

The time seemed right for the large, wealthy, conservative Pasadena church located at 585 East Colorado Blvd. to build its own radio station. The church’s plan was mainly to broadcast the church services, first on Sunday mornings, and later on Wednesday nights too. But the leaders of Pasadena Presbyterian Church also saw this new, modern technology as a way to keep their congregation informed of church events. In addition, they saw radio as a way to bring church services to shut-ins and those too ill to attend. As a side benefit, it's likely that KPPC also attracted some new church members who had previously been merely listeners. But unlike Angelus Temple’s KFSG, which was on the air nearly every day and night, KPPC’s ministry stayed fairly small and localized.

The pastor at that time, Reverend Robert Freeman, liked the idea of having a radio station for his church. To help fund the necessary broadcasting equipment, he proposed that each member of the congregation donate 5 cents toward this new radio station. This probably took place during 1922 or early 1923 during the first wave of radio broadcasting in Southern California. The equipment for KPPC was purchased with the donations from the church members. That first broadcast equipment for KPPC ended up costing between $5,000 and $10,000, according to James Mason. The church had been founded in 1875 and it was hoped to have their radio station ready and on the air for the 50th Anniversary of the church in 1925. David Black, a prominent church layman and later administrator, helped obtain the original license, which the government assigned as number BR-34. (This was simply a bookkeeping number. It did NOT mean that KPPC was the 34th radio station in the United States! In chronological order, KPPC was the 40th radio station to receive its broadcast license in Los Angeles and Orange Counties, although only slightly more than half of those actually got on the air. There were well over 500 United States radio stations licensed in 1922 alone, so I’m not sure how this claim that in 1924, KPPC was the 34th station to go on the air was ever made by the station, as was reported in a 1967 newspaper story on KPPC!)

The call letters KPPC were requested and granted by the Department of Commerce in December of 1924. The necessary equipment was then purchased, installed and tested in preparation for the station’s first broadcast. KPPC was assigned to use 50 watts of power on a wavelength of 229 meters, or 1310 kilocycles. The transmitting antenna was common for the time, a longwire "flat-top" strung between two wooden masts on the roof of the church chapel. The station's control room was located on a lower level of the church tower. (In later years it moved to the attic of the old chapel building, where a projection booth was used as an announcer booth. By the 1960s, KPPC was in the basement of the “new” chapel building.)

Because of the excitement of radio fans in the 1920s over a new radio station, many times the local newspaper carried detailed stories about a station’s construction, complete with many technical details of the antenna, transmitter, microphones, etc. On December 4, 1924 the Pasadena Star-News carried such a story: “Work Begins On Radio Station.” The call letters were not given, but the story indicated that the installation was underway for “the 50-watt radio telephone broadcasting equipment in Pasadena Presbyterian Church.” The church was hoping to have work finished in time to broadcast the first of their Christmas services on Sunday December 21st. The H.L. Miller Electric Company of Pasadena installed the station equipment. The transmitter was a Western Electric number 103-C. According to the story, the plans for the station included “having broadcasting microphones placed in the main auditorium of the church, in the chapel, in the Kirk House, in the belfry, in the main organ loft, in the echo organ loft and in pastor Dr. Robert Freeman’s study.” The article also said the new radio station “would broadcast church sermons, general talks and music from the main auditorium, chimes from the belfry, special music events from the chapel of Kirk House and special talks and musical programs from the study.”

James Mason, who had a long association with KPPC and the church, knows a lot about the station’s history and the history of the church. He told me that the first equipment in 1924 was a combination radio station and public address system for the church. Apparently, when the radio station equipment was switched on, it also made the public address system operate. This also made it possible for any outside radio programs to be brought into any or all of the church buildings. The radio station equipment was powered by a motor generator and storage batteries. In the operating room, the engineer was supplied with a Western Electric radio receiver. Government regulations at that time required broadcasting stations to go off the air if a “distress signal” was sent by a ship at sea. The radio was also used to determine if transmitting operations of KPPC were causing interference with other radio communications.

KPPC’s first official broadcast took place on Thursday, December 25, 1924. That is when listeners to Pasadena’s new station were actually able to hear the Christmas Day services live from the Pasadena Presbyterian Church in their living rooms and parlors. The Christmas Eve edition of the Star-News explained the situation this way:

“It was originally planned to use the broadcaster (KPPC) for the first time last Sunday morning, but installation was not completed in time. It was then arranged to make the Christmas carols on December 25th the first program to be transmitted.” The story reminded readers of the 229-meter wavelength and power of the station, and that the first broadcast would take place the next day (Christmas) at 8 a.m.

George Anton Pohlman was the station's first broadcast engineer and announcer. Luckily for us, he also kept a diary of each broadcast. His entries included the weather, date and time KPPC was on the air, a report on any technical problems, along with Pohlman’s personal comments regarding the speakers and musicians who were heard on KPPC. The first such entry was brief and to the point:

"December 25, 1924 --Thursday, 8 a.m. Weather clear, very cold. About 30 carolers singing Christmas carols from the church pulpit, led by the Rev. Dr. Robert Freeman and Mrs. Roy V. Rhodes, with George H. Woods at the organ. Later - at 10 o'clock, a half-hour Christmas service by Dr. Freeman. Broadcast reception was very clear." That’s how KPPC radio began nearly 82 years ago. I have also learned that Mr. Pohlman was reportedly one of the most-involved people who helped put the station on the air, as part of his senior class project while he attended Occidental College in Los Angeles. The first broadcast was a success.

On Friday December 26th, the Star-News headline said it all: “Broadcasting Station Is Now Open.” The newspaper story proclaimed, “The broadcasting station of the Pasadena Presbyterian Church was used for the first time on Christmas Day and hundreds of residents of Pasadena and vicinity enjoyed the music and Christmas message. The church has been receiving reports all day today as to how successfully the new station worked. Many spoke of how distinct and clear the message came and of the pleasure it gave family groups all over the city to ‘tune-in’ on these initial performances.” The story also said several people reported they could not locate the station (on their radios). It was explained by engineers at the church that the reason was most likely that “their receiving instruments were not adjusted for such a low wavelength as 229.” The Broadcast Band had been expanded a year earlier to include 550 to 1350 kilocycles, but some older radios could not tune the entire range up to KPPC’s 1310-AM dial setting. Another newspaper story on KPPC that week reported that after the first broadcast on Christmas Day, the station would be on the air every Sunday at 11 a.m. and 7:30 p.m. to broadcast the church services. KPPC-AM continued to broadcast the Sunday morning services from the church until it went off the air in 1996.

A little more than two weeks later, another diary entry from G. Anton Pohlman for Sunday, January 11, 1925, 11 a.m. stated: "First broadcast of the church's Tower Chimes, as played by Samuel Allen." The chimes usually signaled the start of a KPPC broadcast and were very familiar to radio fans in Southern California in the 1920s. Incredibly, Allen continued playing those chimes into the early 1960s! On Wednesday January 25, 1925, the Star-News radio listings in the newspaper showed that KPPC would broadcast the Wednesday night church services for the first time, at 7 and 9 p.m. Another newspaper story from January of 1925 gives an example of the novelty of radio broadcasting in those days. The article says KPPC would broadcast both of the Sunday services starting at 10:30 a.m. and 6:45 p.m. It went on to say, “Anton Pohlman, the church’s radio operator and announcer will broadcast in detail both programs, giving names of organ and choir numbers and reading first verse of same, scripture and text references, number and page of responsive readings, etc.”

By February of 1926, KPPC was on the air Monday through Saturday nights at 7:30 with the tower chimes and some brief announcements, followed at 7:45 by a short address. The Sunday schedule consisted of going on the air at 10:30 with some announcements, followed by the 11 a.m. church service. Another broadcast took place at 7 p.m. that evening and lasted about an hour. On Wednesday nights KPPC broadcast that evening's lecture and prayer service, beginning at 7 p.m. The nightly broadcast of the tower chimes was short lived however, and the station soon settled on its twice-a-week broadcast schedule, which varied only a few times during the station’s existence. Radio Doings magazine promoted the station by listing its program schedule quite often, starting in 1925.

In those early days, KPPC shared 1310 kilocycles with KFQG, but that station went off the air in May 1925. Unfortunately for KPPC listeners, starting on June 15, 1927, KPPC again had to share their frequency, this time with a brand new station just down the road in Burbank, KELW. Was relief in sight? On February 20, 1928, KPPC was moved to 950 kilocycles by the new Federal Radio Commission, but on that same day, the FRC ordered KPPC to share the 950 dial position with station KPSN, owned by the Pasadena Star-News, which was immediately adjacent, next-door to KPPC. Then on November 11, 1928, the FRC reallocated the entire broadcast band and this time moved KPPC to 1200 on the dial. The station now had to share time with KFWC-Ontario (which later moved to Pomona and then San Bernardino). But, since the church had decided they only needed to be on the air on Sunday and Wednesday, a time-share agreement on the same frequency wasn’t such a bad thing.

FREQUENCY MOVE IN 1929 SEALS KPPC’S FATE

One year later, on November 15, 1929, KPPC was moved from 1200 to 1210 kilocycles, along with KFWC, as its owners immediately changed the San Bernardino station’s call letters to KFXM. On this same date, the wise folks at the FRC also assigned Los Angeles station KGFJ to move from 1420-AM to 1200-AM. This radio dial position was only 10 kilocycles away from KPPC!! Even though KPPC went on the air only twice a week, its transmitter was just 10 miles away from adjacent channel KGFJ. This situation would be a point of contention between the two radio stations for more than 50 years. This pretty much sealed KPPC-AM’s fate, preventing it from becoming a full-time station. However, it seemed the church wasn’t interested in that, at least early on. I understand that in later years, when they tried to move to another frequency, there were no empty spots on the L.A. radio dial and they were locked into a two-day on-air schedule. The 50-watt KPPC also had to live with interference from the 100-watt KGFJ, and make an agreement with co-channel KFXM as to when they could divide the broadcast time on 1210-AM between them. (This comment is my “Monday morning quarterback” session, long after the game is over. But, I’m wondering, if the church wanted to be on the air more than two days a week, why KPPC didn’t apply to the FCC for a possible move to an open frequency without any local station interference? They could have possibly applied to move to another ‘local channel’ such as 1310 or 1420 before 1941, or maybe 1490 after 1941, before Burbank laid claim to it. Such a move would’ve given them more power and a better signal in their listening area.)

In accordance with these time-share arrangements, KPPC managed to continue its short on-air schedule, usually for Sunday and Wednesday. However, during the depth of the Great Depression, it is interesting to note the schedule for both stations. In October of 1934, KPPC was on EVERY day from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. KFXM didn't sign-on until 3:00 p.m., but then went off at 6 p.m. KPPC got its turn to broadcast again from 7:30 till 9 p.m. and KFXM finished its broadcast day, going on again from 9 p.m. until midnight.

MORE THAN A RELIGIOUS STATION

Though KPPC is known early on for its years as a church-owned station, it should be noted that many secular events were also aired. These included broadcasts of current events, cultural and civic programs, along with educational material. The March 4, 1925 inaugural address of President Calvin Coolidge and the oath administered by Chief Justice William Howard Taft were heard over KPPC, with NBC's Graham McNamee announcing. A much bigger and well-known station, KFI, also broadcast this newsworthy event, but the church obviously felt it was important enough to have Pasadenans hear it over their very own station. Pasadena High School graduation exercises were also broadcast that year. Other events covered in KPPC's early years included a radio show in Pasadena sponsored by the local Radio Dealers Association. In April 1925, Helen Keller spoke over KPPC during her west coast speaking tour that year and Christine Miller sang. The diary of Mr. Pohlman indicated that the two famous women took time to visit the station's broadcast facilities.

KPPC continued throughout the 1920s and '30s, in fact, as long as the church owned it, as a non-profit station, which operated as a community service. It managed to stay on the air through church finances and the voluntary services of its congregation, who served on the Radio Committee and worked as engineers and announcers. But the years of the Great Depression may have been hard on the station. There were times in 1933 and '34 where it was listed as "silent", or off the air. This may have been a mistake or misprint in RADEX magazine, since one expert on the church and KPPC told me the station never went off the air, but possibly a technical problem kept it from broadcasting occasionally. However, thePasadena Post radio logs for March of 1933 do not list any broadcasts for KPPC that month, and seems to match the RADEX magazine listing, which said KPPC was off the air at that time. The Pasadena Post does show KPPC on the air with its regular broadcasts in October of 1934, silent again in January of 1935, but on the air the remainder of that year. So far, I’ve found no explanation for the irregular broadcast schedule of KPPC, which was printed in the newspapers for those months.

By 1936, KPPC again had to cut back its broadcast schedule and was on the air for only a short 8 and 3/4 hours a week, including the Sunday services and a Wednesday night prayer service. This schedule continued into 1938, when the station was on the air Sundays from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. and 6:45 p.m. to 9 p.m. KPPC would return to the air on Wednesday nights from 7 p.m. to 9:30 p.m. By this time, David Black was Station Manager and N. Vincent Parsons was the KPPC announcer who doubled as chief engineer. Parsons had held that position since at least 1933. He remained with KPPC into the late 1940s, when he entered the new field of television and was eventually hired at KNXT, channel 2 in Los Angeles.

In 1935, KPPC applied to the FCC to double its output power from 50 to 100 watts, while continuing to share time on 1210-AM with KFXM. The church also had asked that daytime power on Sundays be raised to 250 watts. This was denied, due to the interference that would be created with adjacent channel KGFJ on 1200 kilocycles, which was only 10 miles away from KPPC. The Federal Communications Commission report on these two issues stated the following: “The recommended separation between two such stations such as KPPC and KGFJ is 53 miles, whereas the actual separation is only 10 miles. On their existing frequencies, and with their present assigned power outputs, there is now interference experienced between the applicant station and KGFJ. However, the Commission has before it a situation which already existed before it became the licensing authority. If the application before us now were granted, seeking an increase in power of Station KPPC to 100 watts night, 250 watts day, the interference which exists between KPPC and KGFJ would be increased considerably during the hours that Station KPPC operates, to Station KGFJ’s detriment. However, with respect to the application of Station KPPC to increase power to 100 watts, the Commission is of the opinion that it is in the public interest that all local stations operate at night whenever possible with the maximum power permitted under the rules. The granting of this application would serve to equalize the interference between the two stations; that is to say, such operation would be expected to limit the service area of Station KGFJ to approximately its 3 mv/m contour in that portion of it service area more distant from Station KPPC. At the same time, interference would also be expected to Station KPPC from Station KGFJ, limiting Station KPPC to its 3 mv/m contour in that portion of its service area more distant from Station KGFJ.”

The FCC acknowledged that KPPC offered at no charge, a high degree of service to its community. Even with its short broadcast schedule, the Commission said, “KPPC gives liberally of its time to other churches and to civic groups, education institutions, city schools, the Red Cross and similar organizations.”

The FCC acknowledged that KPPC would likely grant even more airtime to such groups, but was unable to do so, due to its limited time on the air. The FCC eventually did grant the power increase to 100 watts on April 24, 1936, a power level that KPPC used until 1985. (In 1936, KGFJ was also using only 100 watts, so they were able to stay on the air while KPPC was broadcasting, but KFXM would still go off for KPPC.)(1926 KPPC/KPSN program schedule)

Unlike the competitive situation that exists these days, there was no lack of cooperation between KPPC and its next-door neighbor at 525 Colorado Blvd., the Pasadena Star-News, which owned and operated KPSN, beginning in November of 1925. Not only did both stations share time on 950 kilocycles from February 20, 1928 until November 11, 1928, they also helped one another before then. The Star-News had been printing the KPPC schedule in its daily radio program listings and even some 1926 program listings in Radio Doings magazine showed that some of the Sunday night services of the church were aired over the more powerful 1,000-watt KPSN, apparently when KPPC had technical problems. In August 1927, a "Radio Doings" program listing shows BOTH KPPC and KPSN airing the Sunday morning church service! In April 1931 the Star-News decided to take KPSN off the air forever, after being forced to share-time since late-1928 and only getting as little as 15 minutes per day of airtime on its frequency. The newspaper had clearly lost interest in the radio station. In the end, the FRC had actually canceled the station license due to inadequate technical equipment, and the newspaper did not appeal the decision.

But the paper allowed KPPC to move its longwire transmitting antenna from the church roof to the old KPSN towers. In 1936 when power was raised to 100 watts, KPPC revamped this antenna system, a top-loaded 'T', strung between the two 125-foot towers on top of the 5-story newspaper building. The actual radiating element of the antenna was the 121-foot vertical lead, with the horizontal wire element acting as a capacitive load. The ground system was installed under the tarpaper of the roof, with a fan of copper wire running into a series of strategically placed grounds on a lot next door. Many of those grounds were silver-soldered to buried, large copper stills, reportedly used by bootleggers during Prohibition. They were seized and donated to the church by the government for KPPC's use. The two radio towers supporting the KPPC antenna had the words "Star-News" displayed on each side, a reminder of the past cooperation KPPC had with the paper and the old KPSN. The KPSN call letters were removed from the towers soon after its demise, but the KPPC call letters were never placed on the towers. Sadly, for radio historians, in the fall of 1990 the old KPSN/KPPC towers and longwire 'T' antenna were taken down as well. A new antenna of the same type was placed partly on the roof of the church and ran to the top of a nearby medical building. This could only be seen if you traveled behind the church. The antenna system was new, but the old ground system, including the buried stills, was still used. This antenna was still in place long after KPPC went off the air in 1996.

KPPC SIGNAL HEARD OUTSIDE CALIFORNIA

KPPC engineers tried to satisfy the demands of the DXer (long distance radio buff) over the years. In the 1920s, and to a lesser extent in the 1930s, many radio fans tuned-in at night simply to hear far-away stations. They took part in what would be called “channel surfing” today. The practice of the DXers was to twist the radio dials and listen for an announcer giving the station call letters and the city it was broadcasting from, then tune to the next station to see where it was coming from. Once these radio listeners heard the call letters, they didn’t care about the programming. They moved on to the next frequency to see how far away from their location the next station was located, despite interference, noise and fading signals.

The short twice-a-week schedule of KPPC and its low power made it a prized "catch" for many DXers. During the 1920s and 1930s, its signal was received fairly often on the east coast and elsewhere, due to both the un-crowded conditions of the broadcast band and considerably less man-made noise affecting AM radio than we have today. Here’s a small example of a radio hobbyist who picked up the KPPC signal in northern California. I happen to own a copy of Broadcast Weekly magazine from February 28, 1928 addressed to a man in Santa Cruz. Inside the magazine, there are many pencil markings with notes about what radio stations this person heard, along with the dial markings for the stations on his TRF radio. Most are from outside of California. But at the bottom of the Sunday night program listings, I was surprised to see that the man wrote “KPPC-Pasadena-34-34-35, (church), off 1 minute to 9.” The three numbers refer to the number settings of the three tuning dials used on those TRF (Tuned Radio Frequency) radios of the 1920s.

Even when KPPC was listed as off the air in March of 1933, RADEX magazine reported that KPPC had a special program for DXers scheduled on Friday night March 3rd/Saturday morning March 4th from 12 midnight to 6 a.m. Pacific time. This was a special program on the air all night, as a test to see how far the KPPC signal “got out.” It was quite common at the time for radio stations to do these types of tests programs for radio hobbyists on occasion. By coincidence, I have a photocopy of a verification letter dated February 9, 1933 sent to a man who heard KPPC in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. The letter confirmed his reception of the Pasadena station January 31st and thanked him for the signal report. The letter closed by telling the distant listener that “our next (DX) test will be on the morning of March 4th.” It was signed by KPPC engineer/announcer N. Vincent Parsons. KPPC reportedly got reception reports for this test from as far away as Philadelphia. It’s likely that during the overnight test broadcast that engineer Parsons played phonograph records interspersed with frequent station ID’s, in an effort to see how far KPPC’s signal was ‘getting out.’

Because 24-hour-a-day stations were still rare in those days, and most were off by midnight, KPPC not only had a clear shot to the eastern USA, but it likely had the 1210 channel to itself for much of the DX test. Stations such as KPPC were also heard in those years during periodic late-night frequency checks, since the FCC rules then called for all other stations on that frequency to go off the air during the test. Also, in those days before directional antennas were common, KPPC and other area stations regularly received cards and letters from far-away radio listeners and DXers who had picked up their signal during those late night or early morning hours. We’ve included a 1944 QSL sent out by KPPC to a DXer who heard the station on the east coast. We also have a photocopy of the same QSL sent to a radio hobbyist in Illinois who heard KPPC. The QSL card was designed by N. Vincent Parsons, who had a keen interest in the distant signal reports which KPPC received while he was with the station.

KPPC engineers tried to satisfy the demands of the DXer (long distance radio buff) over the years. In the 1920s, and to a lesser extent in the 1930s, many radio fans tuned-in at night simply to hear far-away stations. They took part in what would be called “channel surfing” today. The practice of the DXers was to twist the radio dials and listen for an announcer giving the station call letters and the city it was broadcasting from, then tune to the next station to see where it was coming from. Once these radio listeners heard the call letters, they didn’t care about the programming. They moved on to the next frequency to see how far away from their location the next station was located, despite interference, noise and fading signals.

The short twice-a-week schedule of KPPC and its low power made it a prized "catch" for many DXers. During the 1920s and 1930s, its signal was received fairly often on the east coast and elsewhere, due to both the un-crowded conditions of the broadcast band and considerably less man-made noise affecting AM radio than we have today. Here’s a small example of a radio hobbyist who picked up the KPPC signal in northern California. I happen to own a copy of Broadcast Weekly magazine from February 28, 1928 addressed to a man in Santa Cruz. Inside the magazine, there are many pencil markings with notes about what radio stations this person heard, along with the dial markings for the stations on his TRF radio. Most are from outside of California. But at the bottom of the Sunday night program listings, I was surprised to see that the man wrote “KPPC-Pasadena-34-34-35, (church), off 1 minute to 9.” The three numbers refer to the number settings of the three tuning dials used on those TRF (Tuned Radio Frequency) radios of the 1920s.

Even when KPPC was listed as off the air in March of 1933, RADEX magazine reported that KPPC had a special program for DXers scheduled on Friday night March 3rd/Saturday morning March 4th from 12 midnight to 6 a.m. Pacific time. This was a special program on the air all night, as a test to see how far the KPPC signal “got out.” It was quite common at the time for radio stations to do these types of tests programs for radio hobbyists on occasion. By coincidence, I have a photocopy of a verification letter dated February 9, 1933 sent to a man who heard KPPC in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. The letter confirmed his reception of the Pasadena station January 31st and thanked him for the signal report. The letter closed by telling the distant listener that “our next (DX) test will be on the morning of March 4th.” It was signed by KPPC engineer/announcer N. Vincent Parsons. KPPC reportedly got reception reports for this test from as far away as Philadelphia. It’s likely that during the overnight test broadcast that engineer Parsons played phonograph records interspersed with frequent station ID’s, in an effort to see how far KPPC’s signal was ‘getting out.’

Because 24-hour-a-day stations were still rare in those days, and most were off by midnight, KPPC not only had a clear shot to the eastern USA, but it likely had the 1210 channel to itself for much of the DX test. Stations such as KPPC were also heard in those years during periodic late-night frequency checks, since the FCC rules then called for all other stations on that frequency to go off the air during the test. Also, in those days before directional antennas were common, KPPC and other area stations regularly received cards and letters from far-away radio listeners and DXers who had picked up their signal during those late night or early morning hours. We’ve included a 1944 QSL sent out by KPPC to a DXer who heard the station on the east coast. We also have a photocopy of the same QSL sent to a radio hobbyist in Illinois who heard KPPC. The QSL card was designed by N. Vincent Parsons, who had a keen interest in the distant signal reports which KPPC received while he was with the station.

Mike Callaghan, who today is chief engineer for KIIS/fm in Los Angeles, was chief engineer for KPPC-FM and AM from March of 1970 to October of 1973. Mike told me in an email that with KPPC-AM’s type of wire transmitting antenna, there wasn’t much of a ground wave for a good local signal and at night, the signal from the antenna tended to go “straight up into the air.” Mike added that even with the crowded AM band conditions compared to the 1930s and ‘40s, KPPC-AM still got DX reports from as far away as the Hague in the Netherlands! When Mike showed the reception report to the general manager, his comment was, “Great, the AM gets to Holland, but I can’t hear it in Rosemead!!!” Mike said he even heard bits and pieces of the 100-watt signal himself while camping in Oregon, but we’ll save that story for later in the article.

(The 1989 letter I got from KPPC’s station manager said they still received an occasional report from DXers in New Zealand, who used very long wire antennas aimed at North America. KMike Callaghan, who today is chief engineer for KIIS/fm in Los Angeles, was chief engineer for KPPC-FM and AM from March of 1970 to October of 1973. Mike told me in an email that with KPPC-AM’s type of wire transmitting antenna, there wasn’t much of a ground wave for a good local signal and at night, the signal from the antenna tended to go “straight up into the air.” Mike added that even with the crowded AM band conditions compared to the 1930s and ‘40s, KPPC-AM still got DX reports from as far away as the Hague in the Netherlands! When Mike showed the reception report to the general manager, his comment was, “Great, the AM gets to Holland, but I can’t hear it in Rosemead!!!” Mike said he even heard bits and pieces of the 100-watt signal himself while camping in Oregon, but we’ll save that story for later in the article.

The 1989 letter I got from KPPC’s station manager said they still received an occasional report from DXers in New Zealand, who used very long wire antennas aimed at North America. KPPC even received one letter about that time, from a woman in Oklahoma who claimed that she picked up the station’s signal in her teeth! I first heard about the unusual Pasadena AM station around 1974 or so, but I didn’t try to listen to it until much later. When I lived in Anaheim in 1982, it was a thrill for me to pick up KPPC via its groundwave signal, just because of its 100 watts of power and the fact it could be heard broadcasting only two times a week. Using my Kenwood R-1000 communications receiver and a good loop antenna, I was able to partially block out the San Bernardino station with lowered-power and hear the program from KPPC clearly. At only 45 miles away, the 100-watt signal was loud enough to make out the music and speech by the announcer, but still had a “far-away” quality to the sound in my radio’s speaker. After listening to a dj play records on a Gospel music show for about an hour, I heard the recorded legal ID at 2 p.m. A woman’s voice said, “The difference is in the music, AM 12-40, K-P-P-C, Pasadena.” Next, a male voice came on the air to talk about the final half-hour of “Gospel Concert” for the afternoon. I sent a cassette tape recording of my Sunday afternoon reception to the chief engineer. In his reply to me, Steve Cilurzo stated that after he listened to my recording of the station, he felt KPPC was doing well for its low power and center-fed “T” type wire transmitting antenna. I think I may have tuned into KPPC-AM only once or twice after that to see if I could again hear its signal, but that afternoon in 1982 is my only clear memory of actually listening to KPPC for any length of time. I’m happy to report I still have my recording of that KPPC broadcast heard in Anaheim in 1982. PPC even received one letter about that time, from a woman in Oklahoma who claimed that she picked up the station’s signal in her teeth! I first heard about the unusual Pasadena AM station around 1974 or so, but I didn’t try to listen to it until much later. When I lived in Anaheim in 1982, it was a thrill for me to pick up KPPC via its groundwave signal, just because of its 100 watts of power and the fact it could be heard broadcasting only two times a week. Using my Kenwood R-1000 communications receiver and a good loop antenna, I was able to partially block out the San Bernardino station with lowered-power and hear the program from KPPC clearly. At only 45 miles away, the 100-watt signal was loud enough to make out the music and speech by the announcer, but still had a “far-away” quality to the sound in my radio’s speaker. After listening to a dj play records on a Gospel music show for about an hour, I heard the recorded legal ID at 2 p.m. A woman’s voice said, “The difference is in the music, AM 12-40, K-P-P-C, Pasadena.” Next, a male voice came on the air to talk about the final half-hour of “Gospel Concert” for the afternoon. I sent a cassette tape recording of my Sunday afternoon reception to the chief engineer. In his reply to me, Steve Cilurzo stated that after he listened to my recording of the station, he felt KPPC was doing well for its low power and center-fed “T” type wire transmitting antenna. I think I may have tuned into KPPC-AM only once or twice after that to see if I could again hear its signal, but that afternoon in 1982 is my only clear memory of actually listening to KPPC for any length of time. I’m happy to report I still have my recording of that KPPC broadcast heard in Anaheim in 1982. )

As mentioned previously, KPPC, along with most other early stations, did not stay on its original assigned frequency. On March 29, 1941, the FCC shifted KPPC's frequency a final time, from 1210 to 1240 kilocycles. This was in accordance with the new North American Regional Broadcast Agreement. KPPC’s share-time partner, KFXM, was also assigned to move from 1210 to 1240 on the radio dial. In all those years, the agreement called for KFXM to leave the air during the hours that KPPC was scheduled to broadcast. In 1947, KFXM moved from 1240 to 590 on the AM dial and a new station in San Bernardino took over the license 1240 kilocycles.

FROM SHARING TIME TO SPECIFIED HOURS

The time-share plan on 1240-AM for KPPC ended three years before KFXM’s frequency change, on June 13, 1944. The FCC ruled on that date that KPPC would be limited to going on the air only Wednesday evenings and all day on Sunday. KPPC had been broadcasting only on those two days already for several years, so the FCC decided to make it official.

KPPC's limited hours of operation were designated as "specified hours." Under this plan, the FCC said KPPC would be allowed to broadcast Sundays and Wednesdays nights only, but KGFJ-1230 in Los Angeles now had to lower its power to 100 watts to reduce the amount of interference to KPPC. The 1240 station in San Bernardino could now stay on the air while KPPC was broadcasting, but also was required to lower it power to 100 watts. Later, when the daytime power of the San Bernardino station was allowed to increase to 1,000 watts, they had to lower their day power to 500 watts when KPPC operated. In the late-'40s, KGIL-1260 came on the air in San Fernando, posing another interference problem to KPPC. This new station, which had a directional antenna pattern in later years, had to use its night directional array on Sundays when KPPC came on the air. All this protection for 100-watt KPPC was due to a "grandfather" clause in FCC rules and regulations. Since KPPC came on the air before KGFJ and 1240 in San Bernardino, and well before rules that required a radio station to operate at least 18 hours-a-day, the FCC said the station deserved to be protected from interference from the other adjacent and co-channel stations nearby. The other station owners hated it, but they abided by this rule, which lasted 41 years, until 1985!

KPPC 1940s PROGRAMMING

During the World War II years, KPPC was as busy as ever. It was broadcasting its church-related programs, along with other shows of interest at the time. The Wednesday night broadcast from KPPC had some heavy competition from the ‘prime-time’ evening entertainment shows on the air nationwide on KFI/NBC Red Network, KECA/NBC Blue Network, KHJ/Mutual Broadcasting System and KNX/CBS Network. But, members of the church congregation in Pasadena were probably quite loyal to their hometown radio station. In 1941, a sampling of the KPPC programming included “Music of the Masters,” a dramatic show called “County Seat,” a program featuring the Pasadena Hobby Club, another drama called “Cosmopolitans” and a show on National Defense. Also in 1941, KPPC aired a local quiz show featuring businessmen and other important people from the community competing against one another. The showwas called “Pasadena Preferred”, and the idea was for the contestants to answer questions related to important facts about Pasadena. Service clubs such as the Lions Club, Kiwanis, etc. sponsored the program. A 1943 Radio Life magazine listing shows that the first program aired on a Wednesday evening at 7 p.m. was for the Pasadena Department of Recreation. There were also programs that night featuring the Red Cross, Occidental College and a talk on Civil Defense. (As for the Occidental College broadcast, research has found that Charles Lindsley, a Professor of Speech at Occidental from 1923 to 1960, produced 23 religious/educational broadcasts for KPPC in 1942 and ’43. For several years, there were many Pasadena Presbyterian Church members who were trustees of Occidental College and major donors. Professor Lindsley was also Director of Radio for Pasadena Playhouse, which also produced some radio programs for KPPC over the years).

A half-hour panel discussion show called “Let’s Talk It Over” was also broadcast, and featured several church leaders and various laymen. This was a regular KPPC feature for many years. A Sunday night show in 1943 was a religious drama called “The Clarion Call”, which aired at the same time over KFWB. It probably doesn’t sound exciting by today’s standards, but it was likely fairly typical of radio production techniques used at that time. Also in the early years, the station featured organ recitals by George A. Mortimer and Robert W. Allen, former organists at the church. By the late-1940s, KPPC was also airing a weekly locally produced show called “Story Time.”

KPPC nearly doubled its hours on the air for its 20th Anniversary in December of 1944. The station was on the air for 12 hours on Sundays, from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. The Wednesday evening broadcasts continued to last from 7 to 9:30 p.m., for a total of 14 ½ hours on the air per week.

A 1950s LOOK INSIDE KPPC

It may be impossible to come up with a comprehensive list of LARP who got started in broadcasting at KPPC, especially during the station’s early years. One big name from Los Angeles radio who got his earliest training in broadcasting at KPPC was Vince Campagna, who was a longtime newscaster at KFWB from 1969 to 1997. Vince was at KPPC from the late-1940s into the early-1950s, according to James Mason.

I have two specific sets of KPPC memories from LARP who were there in the 1950s. Fred Volken is a well-respected radio engineer in Southern California. He is the man who redesigned the KFI auxiliary antenna’s tuning network some time ago to support the current 25,000-watt operation. This was before the main KFI tower was destroyed in a plane crash in late-2004.

Fred learned about KPPC from friends in school. He worked there between 1948 and 1952, first as an unpaid volunteer technician and later as chief engineer. In an email to me, Fred said, “The two paid part-time positions at the station then were the station manager and chief engineer. Many of the other persons who worked at KPPC as volunteers were also in school (in high school or attending Pasadena City College or the Pasadena Playhouse theater school, for example). There never seemed to be a shortage of persons to make up a talented and skilled program and technical staff. The station’s standards for program quality were remarkably high, and there were always enough experienced knowledgeable and talented people involved in a variety of ways to make the experience there a valuable one.

In the earlier years, the offices and studios were in the Kirk House building on Union Street (which was also used for the church school), and the transmitting equipment was located on the top floor of the former chapel building on Colorado Blvd. In addition to the regular Sunday morning church service, the broadcasts included talks given by church ministers, organ recitals and various other music recitals, poetry readings, discussion programs, a weekly dramatic presentation that was produced (and even written) by volunteers at the station, major music programs presented by the church, occasional remote broadcasts for charitable events, programs of interest produced outside the station (and received on transcription discs), and a lot of recorded classical music.” Fred also recalled, “A big event in those days was the temporary installation of a new transmitter in the Kirk house building to permit continued broadcasting, while the former chapel building was replaced with a new chapel and parish house building that was designed to include space for both offices and studios and the transmitting facilities for KPPC. Another exciting event was the acquisition of a new Ampex tape recorder that permitted high-quality recording of programs for later broadcast.”

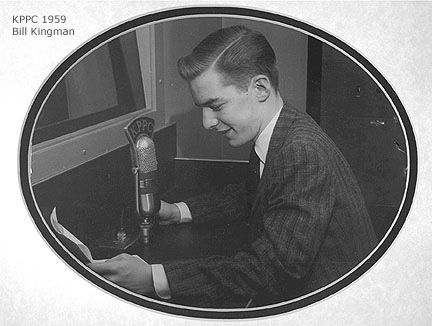

Bill Kingman got his start in radio at KPPC in 1959 and ’60. Since 1961, Bill has resided at Lake Tahoe as a disc jockey and chief engineer at Tahoe’s local stations. Bill recalled how he got involved with KPPC:

”KPPC was my first station. It was March 1959, I was 17, and I was at the church one evening – they actually had their own hardwood floor roller-skating rink there – and after skating I wandered down to the basement. I didn't know they had a radio station, but I spied it and was entranced. It happened to be a Wednesday evening when KPPC was on the air. An older distinguished-looking gentleman who kind of resembled WKRP's Arthur Carlson (the late actor Gordon Jump) saw me ogling at the hallway window and asked, "Well, young man, are you interested?" Five minutes later I was seated in the main live music studio, reading the back cover of a classical music LP into a boom microphone. That man was Del Mar Reynolds, the Program Director, and he was auditioning me from his perch in the control room. I was too numb to be nervous! He came out and said, "You volunteer your time, and we’ll teach you radio." After a few Sundays of polishing microphones, cleaning equipment, learning the board, and learning to respect the whole operation, he put me on the air to "board-op" and do station ID's. Shortly, he gave me my own half-hour show each Sunday night at 8:30, which I called "Hi-Spot" for some reason I've totally forgotten. But I've never forgotten the thrill of my first listener phone-calls and letters – yes, in those days listeners would write letters, and I still have my first letter!”

Bill shared several other KPPC memories for me: “The people I knew at KPPC in 1959 included Dave Scott, a young prodigy and talent who syndicated his show to 200 stations, but who died of leukemia at age 25; chief announcer Bob Holden, who was still putting KPPC’s transmitter on the air for the 11 a.m. Sunday church service when I visited in 1996; chief engineer Clayton Blake, an electronics genius; and program director Del M. Reynolds who auditioned and hired me. Other announcers were Bob MacLeod, Walter Eby, Steve Elliot, Robert Scott, Dave Berkus and other names now escaping me.”

Bill went on to describe the KPPC studios at that time, some of the equipment and what the station aired: ”KPPC was built like classic big network facilities for live broadcasts, with a glassed-in control booth facing each live studio. KPPC had two such studios, each with elevated-floor control booths, all Collins electronics, RCA microphones, and Gates turntables. Cart machines had not been invented yet. KPPC operated 7 a.m. – 12 midnight on Sundays and 7 p.m. – 11 p.m. Wednesdays. This schedule included the Pasadena Presbyterian Church services on Sundays and Wednesdays, plus live broadcasts of the church bells in the steeple, as well as concerts by the church choir. Programming, recorded or live, was wholly classical or religious until late evening, when it would lighten to Percy Faith, Mantovani, et cetera.”

By 1962, KPPC had mostly the same staff members that Bill Kingman worked with a few years earlier: Clayton Blake was the station manager, and had been there since 1947. He became chief engineer in 1952 and designed the station’s main studio. Robert Holden was chief announcer and maintenance engineer; Del Reynolds was program director and John Boyd was transmitter engineer.

Pasadena Presbyterian Church officials had wanted to make KPPC-AM a full-time station for a long time, but when that became impossible under FCC rules for the AM band, they applied for an fm station license. Bill Kingman had left KPPC by then. Here, he tells how he learned of the church’s new radio station:

“In the fall of 1960, I was at KPER, Gilroy. Each late afternoon, the UPI teletype would churn-out the FCC's actions of the day. One day --in October, I believe UPI reported: "...granted 106.7 mc to Pasadena Presbyterian Church.” This decision came after a lengthy contested battle against another applicant. I knew my KPPC buddies had been sweating this for a long time. I promptly sent a congratulatory telegram to KPPC. Shortly thereafter, my phone rang and Bob Holden was asking, "What are you talking about? Where did you hear this?" He/they were cautiously ecstatic! Apparently my telegram preceded notification from their own attorney!”

It took some time to get their fm station on the air, but it finally happened about 18 months later. It was on May 20, 1962, some 37 years, four months and 26 days after KPPC started on the AM band, that the church put KPPC/fm (now KROQ) on the air at 106.7 MHz. for its first day of broadcasting. The new fm station used a 4,400-watt transmitter (22,500 watts effective radiated power) to supplement the lower-powered AM station. The FM’s 5-bay antenna was attached to one of the KPPC-AM towers, atop the Pasadena Star-News building adjacent to the church. The dedication broadcast on the first night of the new fm included the dedicatory sermon by Dr. Ganse Little. The voices of Dr. Eugene Blake, Dr. Myron Nichols, Dr. Thomas Stone and others were then heard, telling of the trying early days of KPPC and of the compensating rewards that followed. A tape recording was also played of Dr. Robert Freeman, the minister at the time KPPC went on the air in 1924.

Don McCulloch was a new addition to the volunteer staff at KPPC in November of 1962. He went from window washer at the station, to become a board operator, booth announcer and was later promoted to host his own show. Don was a junior at Pasadena High School at the time. He was trained by KPPC engineer Bob Holden and another Pasadena High student worker, James Mason. The previously mentioned Dave Scott Show was a Sunday night feature on KPPC. The former child radio actor played records and interviewed guests in the studio.

McCulloch wrote, “In 1964, KPPC/fm became a commercial station. Mike Stroka was named manager and Bob (Holden) became chief engineer. I survived the transition, but a whole new parade of staffers had begun: David Pierce, Tom Carroll, David Varney, Tom Lewis, Bob Roberts, Graham Alexander, Walt DeSylva, and many others. The variety programming had been replaced by a more homogenous MOR format.” Don McCulloch was part of KPPC and KPPC/fm until early 1966, but returned briefly in 1968 during the station’s “underground” days. (Photo: Bill Holden, mid-1960s)

By this time, Don said they were getting paid for their work on the fm, after it went commercial. He recalled that the fm band was like the “minor league” of radio and one could develop one’s radio skills and talents on an fm station, even in a major market like Los Angeles back then. Don also told me about an unauthorized broadcast he took part in on KPPC/fm with his friends. It happened on the morning of January 1, 1965 after the New Year’s Eve celebration at midnight had died down along Colorado Blvd. McCulloch had teamed up with Bob Roberts for a 9½ hour program every Saturday on the fm called “Weekend.” A mutual friend, Berry Kunz, also took part in the New Year’s radio stunt. Kunz, who had been on the air for KPCS at Pasadena City College (now KPCC), was home from the Army for the holidays, and was heading next to Armed Forces Radio in Korea, known as AFKN. Since Don had the keys to get inside KPPC, the three radio buddies decided to go there next. About 12:30 a.m., one of them decided they should fire up the FM transmitter. Don recalled that they signed back on the air legally with the full station ID, and then proceeded to do an impromptu music and comedy show on 106.7. Don added that since Berry was the ‘funny’ one of the three and did a lot of comedy voices, etc., he was on the air most of the time for this show. It lasted maybe 90 minutes to 2 hours, by Don’s estimate. Looking back on it now, Don says they may have had one phone call the whole time, but due to the low audience for fm at that time, he never heard from anybody, not even church officials, about this ‘renegade’ broadcast after KPPC/fm had officially signed off for the night!

Don says he pulled another similar stunt on the fm station the following New Year’s morning. James H. Mason had been with KPPC before Don McCulloch arrived. James is now chief engineer of KLCS television, channel 58, and has been employed by the Los Angeles Unified School District for 33 years, which owns KLCS. Mr. Mason got his start in broadcasting at KPPC at age 16. He also happened to be a member of the church for many years, until fairly recently. Mr. Mason told me that the church had “youth opportunities” for those interested in working in radio. After washing the windows of the radio station every Sunday for a few weeks, station officials saw that he was serious about wanting to be there. He was gradually trained in announcing, giving a station ID, how to operate the control board and cue up records, mixing audio sources, etc. He was then given his own show on the station along with other responsibilities. He was at KPPC for a couple of years on the AM and FM stations, then left to go to college. In the 1970s after the Sylmar earthquake damaged the church, Mason became involved again with the station and the plans to build a new sanctuary. He left briefly, but came back again in the 1980s to take charge of the Sunday morning church service broadcasts from Pasadena Presbyterian for KPPC, with help from Bob Holden.

The days of station ownership by Pasadena Presbyterian Church were soon ending. The church leaders apparently found that programming and running a commercial fm station full-time was a lot more work than putting their non-commercial AM station on the air only two days a week. KPPC-AM and FM were sold five years after the fm went on the air, but the church kept the 1240-AM transmitter in the basement of the new chapel building, along with its 25 by 35 foot main studio with perfect acoustics (designed by Clayton Blake), two smaller studios, record library, shop, and a reception room. The church rented out the studio and transmitter space to the new owners.

Those new owners, Crosby-Avery Broadcasting, purchased KPPC, effective October 5, 1967. The sale was first reported in the Los Angeles Times on August 12, 1967. The purchase price was $310,000 for the AM & FM. The story indicated that besides the Sunday church services, KPPC-FM/AM was broadcasting news, “middle of the road” music, and a variety of community-oriented public affairs programs. At that time, these community-oriented programs on KPPC included a show called “About Science” featuring interviews by nationally known scientists, arranged in cooperation with Caltech and distributed by the National Education Network to 110 member stations; “What Is a City” produced by the Pasadena Rotary Club, and programs by the League of Women Voters of Pasadena, Pasadena Coordinating Council and the Pasadena Arts Council. The newspaper story indicated that the AM signal reached a distance of about 55 miles, which may have been a generous estimate for the signal to be heard on the average AM radio of the day. Station officials were also quoted as saying the station would likely remain in Pasadena, but at a new location. However that did not take place until 1970.

In 1967 the station had a staff of 10, including station manager Edgar Pearce and program director Bob Mayfield. The church had put the two stations on the market about a year earlier. Pearce told the Times the fm had not shown a profit for the church, but added, “…its income had markedly increased in the past several years.” Church officials reportedly felt the money used to subsidize the AM & FM could be better spent elsewhere. Pearce said, “A commercial effort such as radio in the non-commercial atmosphere of the church is just not compatible.”

The new owners would soon use KPPC/fm to change the course of L.A. radio. However, the new licensee was still required as a condition of the station sale, to continue broadcasting the Sunday morning services of Pasadena Presbyterian Church over KPPC-AM.

By this time, 1240 AM was an obscure weak signal buried among the many more-powerful AM radio signals in and around Los Angeles vying for advertising dollars, while KPPC was still non-commercial. That was about to change after nearly 43 years. KPPC-AM's schedule had increased at this time to roughly 22 hours per week: Sundays from 7 a.m. to 1 a.m. Monday morning, and Wednesday nights from 7 p.m. until midnight.

In late-1967, the new ownership and management at KPPC decided to broadcast a format on 106.7/fm that could not be done on AM at the time. It was already on the air at San Francisco fm station KMPX, which was also owned by Crosby-Avery. The programming, initiated by Tom Donahue was called "free form underground" or “progressive rock” radio, which gave the flower children and counter-culture of the day a radio voice of their own. It was unlike any of the Top-40 AM rock music stations in the country, which is what the new KPPC DJ's/air personalities were rebelling against. The decision was made to simulcast the KPPC/fm format on 1240-AM when it was on the air, so KPPC-AM became the first AM station in the U.S. to air such programming. It was a mix of long-play rock album cuts straight from the hippie-drug culture of the time. The disc jockeys were relatively young (though some were a bit older), were into the music and sounded very "mellow," as if they had woken up from a deep sleep and were about to doze off again. They communicated one-on-one with the young listeners. It was a style of talking on the air much different than the fast-talking, high energy DJ's on the pop/rock AM stations of the era. Unlike the AM music stations popular then, these didn’t talk over song intros and didn’t repeat the call letters over and over, or play jingles. They played sets of several songs in a row without talking, and they played longer songs and rock music that couldn’t get airplay on AM radio then. Many young people who found the new FM station liked this format, with very few commercials, and language they could understand. The younger generation opposed to the policies of Presidents Johnson and (later) Nixon, a generation against the Vietnam War and the draft, social injustice, and who didn’t trust anyone over 30, had a radio station they could identify with, when they discovered KPPC. So, KPPC-AM could be credited with helping to start what would become a hugely popular fm radio station in Los Angeles and across the nation, by broadcasting the 106.7 FM station on 1240-AM on Wednesday nights and Sundays.

Here’s a piece of KPPC trivia that I did not find out about until December 2006! According to radio historian Bill Earl, in 1967, Tom Donahue tried to change the call letters of KPPC AM and FM to KHIP, but the station owners would not let him.

According to Ted Alvy’s Web site, KPPC’s change to freeform underground rock music got started with this lineup:

“Exactly 10 years after KFWB went Top 40, Program Director Tom Donahue debuted his KPPC hipster air staff on January 2, 1968 in the basement of the Pasadena Presbyterian Church:

| 6 AM-11 AM |

LES CARTER (KBCA-FM) |

| 11 AM - 4 PM |

ED MITCHELL (KFRC) |

| 4 PM - 9 PM |

B. MITCHELL REED (KFWB, WMCA) |

| 9 PM - MIDNIGHT |

TOM DONAHUE (KMPX-FM, KYA) |

| MIDNIGHT - 6 AM |

DON HALL (KPPC-FM) |

A man named Jay Murley had worked in sales at KPPC-FM/AM back then. He was about to be named FM-AM sales manager in March of 1968, when the air staff went out on strike, and according to Jay, “the fiscal structure came apart.” In 1973, Jay Murley wrote an article for the AM band DX club IRCA (International Radio Club of America), called “Not Your Average Radio Station.” In his story, Murley wrote the following about KPPC:

“With candid discussions of grass, acid, pot and speed, and anything else that might pop into some freak’s head (from studios where contact highs were unavoidable), KPPC-AM quickly became something much different from its original intended purpose. Those studios (in the church basement), thankfully, were separated from the front office by good air conditioning — for staffers and guests who didn’t appreciate contact highs.”

Murley also explained in his article that due to the twice-a-week simulcast, KPPC-AM forced the first exception to the FCC rule then, which said AM & FM stations could not duplicate programming more than 50% of the time if located in major markets. Crosby-Avery Broadcasting claimed in 1968 that it was the fm programming that was intended to be unduplicated, while 106.7/fm was being duplicated about 8% of the time on KPPC-1240 AM on Sundays and Wednesdays.

Murley referred to KPPC-AM’s engineering in 1968 as “atrocious.” He wrote, “Who worries about modulation on a hundred-watt share-time station, when your total music needs involved half-a-dozen pipe organ solos a week, or a few numbers from an off key choir?” As for the previously mentioned KPPC wire antenna system, Murley said KPPC’s flattop was different. While the antenna design looked good, Murley described it this way: “It’s roughly parallel with all the leaky auto ignitions of Colorado Boulevard. It’s anchored to a structure that anchors the printing press of the daily paper published next door. KPPC has a static machine for an AM long-wire (antenna), the sort of static machine that does a job on 1240 and local adjacent channel operations, such as the black-programmed KGFJ on 1230.”

“In spite of its extraordinarily limited schedule and its very limited coverage pattern (barely reaching West Hollywood’s Sunset Strip, never reaching the Pacific and covering less than a third of the Los Angeles market within the half-millivolt contour), this relic out of the past once performed a key function. It offered to the listener without the fm set the chance to sample free-form underground radio during its initial growth period, without having to listen to a friend’s fm. FM set sales skyrocketed among 18 to 24 year-old males, audiences jumped and the rest is history,” Murley concluded. This goes along with what James Mason told me about why the church didn’t keep the AM when the fm was sold in 1967. Apparently, new owners Crosby-Avery wanted 1240-AM to promote the fact that if listeners wanted to hear B. Mitchel Reed and other KPPC DJ's playing this music every day, the listeners should go out and buy a radio with FM, so they could hear KPPC fulltime on 106.7, and not just the two days a week that 1240-AM was on the air with the same music. So, the church replied, if you want the AM station, you’ll have to continue to broadcast our Sunday service. The new owners agreed to that requirement.

One of the KPPC DJ's in those days was Ted Alvy. Ted related to me a story that shows the strange connection between the older AM station and the fm in those days, when many of the “older generation” members of Pasadena Presbyterian Church still tuned into KPPC-AM every Sunday morning to hear the church services from 11 a.m. to noon. However, they soon got an “earful” of what the younger generation liked, when the church service ended on 1240-AM and the noon simulcast began on 106.7/fm and 1240-AM. Ted recalled that incident:

”I remember that sometime in the fall of 1970 (soon after our fm station went full power from Flint Peak), KPPC/fm reclaimed the AM signal on Sundays at noon, when it started its simulcast of our hippie underground music, as KPPC AM & FM for the rest of Sunday (just after the end of the church service broadcast on KPPC-AM). An uninformed part-time deejay once played a ‘blue’ routine by Lenny Bruce just as the simulcast began, and our station gm got a serious complaint from a shocked Presbyterian Church listener. The KPPC studios were now located at 99 South Chester (since Les Carter took over as pd on April Fools day 1970). My memory is a little foggy here, but sometime later our fm may have also simulcast (on 1240-AM) for an hour or two on Wednesday night after the church service ended.”

According to then-chief engineer Mike Callaghan, a similar incident was heard over KPPC-1240 when the Sunday church service ended earlier than scheduled, due to technical problems:

“A fraternity brother of mine, Mike Mathieson, was running the board at 99 S. Chester one Sunday morning, when the mike at the Church suddenly opened and a hurried voice said, "This concludes this morning's service from the Pasadena Presbyterian Church. We now return you to the main studio.” Period. No warning, no nothing. (The church's console had started smoking). Mathieson had absolutely NOTHING cued up or ready to go. Veteran dj Don Hall was pulling records for his 12 Noon shift, and he handed Mathieson an LP and said, "Here, play this!" Mike grabbed the record and, greatly relieved, started tracking it. "GIVE ME AN 'F' -- GIVE ME A 'U' -- GIVE ME A 'C'.......” – It was The Fish Cheer From Woodstock. The old ladies tuned into ‘God Squad’ never even had a chance to turn it down. Mathieson didn't say a word. He just stood up, lifted his license off the wall, and walked out the door, never to come back.”

KPPC STRIKE OF '68 BRINGS CHANGES

KPPC had its share of growing pains and problems, just a few short months after the sale and format change to “free-form underground” rock. Both KPPC/fm and sister-station KMPX DJ's in San Francisco went on strike at 3 a.m. on Monday March 18, 1968. Ted Alvy explains how and why this took place:

|

“KPPC

and KMPX employees went on strike against harassment by the management

and their attempts to prevent artistic and personal freedoms by

replacing the long haired, bearded, or barefoot employees who created

success at both stations. Tom Donahue resigned his management position

to join the strike. Management bled both operations financially,

as checks bounced week after week while most of the salaries were far

below the average in the industry, often below the level of decent

subsistence. Management misrepresented the goals of the striking

employees in order to induce people to work as scabs." (Photo: Ted Alvy) |

Alvy went on to say, “I believe that KPPC/fm had two amazing Underground Radio airstaffs: if KMET had hired the KPPC air staff with B. Mitchel Reed, Tom Donahue and Les Carter in June 1968, KMET would have revolutionized radio in Los Angeles, and across the country, as it would’ve made lots of money playing lots of great music, with many imitators; if the program director Les Carter’s creative air staff had not been fired on October 24, 1971. The freedom given to intelligent deejays at KPPC was responsible for its creative success.”

Charles Laquidara, who had an incredibly long and successful career in rock radio in Boston as host of his Big Mattress morning show on WBCN until 1996, got his start in radio at KPPC. After getting his Bachelor’s degree in theater arts from Pasadena Playhouse, Charles tried radio announcing as a job, while seeking acting roles in Hollywood. Charles was at KPPC twice, first in 1965 and again in ’68 after the church had sold the FM and AM stations. In an email to me, he passed on these memories: