|

www.theradiohistorian.org

Copyright

2023 - John F. Schneider

& Associates, LLC

[Return

to Home Page]

(Click

on photos to enlarge)

This image shows the complete installation of station

6XAK in Hamburger's Department Store, as published in "Radio News",

December, 1921.

E. J. Arnold and H. Berringer operate the

transmitter of station 6XAK; "Los Angeles Evening Record", October 8,

1921.

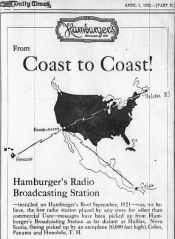

This advertisement was placed in the "Los Angeles

Times" on April 1, 1922.

Oliver Garretson and Charles Austin are seen

here making a KYJ broadcast, dated June 15, 1922.

This program schedule for KYJ appeared in

"Radio Doings" Magazine on December 16, 1922

|

|

The KYJ Story:

This

5-watt radio station was owned by the Leo J. Meyberg Company and had a

‘studio’ on the top floor of the M.A. Hamburger's Department Store

(which became the May Company in 1923). The store was located at

the corner of 8th and Broadway in downtown Los Angeles. KYJ was

also known as “Hamburger's Radiophone.” 1

Licensed: December 9, 1921 (Earlier: 6XAK October 1, 1921)

Final broadcast: December 31, 1922

License Deleted: May 1, 1923

Transmitter power was 5 watts initially, and increased to 50 watts on

April 27, 1922.

Frequency history:

833 kilocycles/360 meters December 9, 1921

833 kilocycles and 619 kilocycles (485 meters) March 22, 1922

(485 meters was used at the time for weather and market reports only)

6XAK:

The Hamburger Radiophone began broadcasting on October 1, 1921, as 6XAK

on 310 meters or about 968 kilocycles. The station was built and

installed by Mr. E.G. Arnold and Hall Berringer, who was sales manager

of the Western Radio Electric Company. This company also owned station

6XD (later KZC/KOG), which Berringer called “the first broadcasting

station in Southern California." In the Los Angeles Evening

Express on September 30, 1921, a story on 6XAK reported that Mr. Arnold

and Mr. Berringer were both radio engineers of the Leo J. Meyberg

Company. The Hamburger’s store used their new radiophone station

to broadcast music and news, and for advertising purposes; especially

to sell phonograph records and the radios and radio parts that were on

display in the store's radio department. Many other Los Angeles radio

supply stores and electrical stores would also soon start a small radio

station to promote their business and encourage interest and sales of

radios and related equipment. The “wireless concerts” transmitted by

the Hamburger’s radiophone station were publicized often in more than

one Los Angeles newspaper.

In the October 15, 1921 edition of “The Talking Machine World,” a small

item on page 101 describes the wireless broadcasting station on

Hamburger’s roof: “Harry N. Briggs, general manager of the music

department at Hamburger’s has arranged for the transmitting by wireless

of the six latest Brunswick records daily at 3 p.m. and 8 p.m., from

the roof of Hamburger’s Department Store. The records are played

on a Brunswick phonograph and announcement is made by the

operator. The wireless is an extremely powerful instrument and

operates at a radius of 1,500 to 2,000 miles.”

Three months later, “The Talking Machine World” from January 15, 1922

printed a similar article about the wireless phonograph concerts from

Hamburger’s Department Store in Los Angeles helping to increase sales

figures in its phonograph department. Quoting from the story, it

reads, “A short time ago, wireless operators, both amateurs and

professionals were surprised to get the following announcement through

their receivers: “This is experimental station 6XAK speaking,

Hamburger’s wireless station, located on the roof of the store.

Commencing today and continuing for an indefinite period, there will be

various concerts and other announcements. We will now have a

selection from the phonograph.” Then followed one of the latest

records, and thousands of radio operators listened in while Hamburger’s

gave a concert lasting from 4 to 5 p.m. Announcement of the new

service was made in the papers with the statement that in addition to

the afternoon concerts, the store will give concerts on Monday,

Wednesday and Saturday nights, from 8 to 9 o’clock, and will later

establish a service between 8 and 9 o’clock in the morning.”

Every afternoon from 4 to 5 p.m., the store sent out a “free radio

concert” for the increasing number of people with radios. By

October of 1921, the fame of the Hamburger radio station had spread so

quickly, that when the Scotti Grand Opera Company was in Los Angeles,

four famous opera singers looked for the store, and arranged to sing

into the 6XAK transmitter. Advance publicity of the event

resulted in thousands of radio listeners tuning in that day. The

station also broadcast results each day of the 1921 World Series to

Southern California baseball fans. When the U.S. Department of

Commerce began to license radio stations for the purpose of

broadcasting music, news, talks, etc. to the general public, 6XAK

applied and became radio station KYJ on December 9, 1921.

KYJ:

Bertam O. Heller was KYJ’s first engineer/operator, but he later left

KYJ to get KWH on the air for the Los Angeles Examiner, and became that

station’s chief engineer. Oliver S. Garretson, an amateur

radio operator and wireless pioneer in Southern California, rebuilt the

KYJ equipment and became chief engineer for a few months. He

increased KYJ’s power from 5 to 50 watts on April 27, 1922.

The Los Angeles Evening Express newspaper joined with station personnel

to select the programming. One schedule for KYJ in late-1922

shows that it was on the air seven days a week. The station was

typically on the air for 1 or 1-1/2 hours in the afternoon. The

station came back on for 45 minutes in the evening. The listening

public of the day tuned in to hear a variety of talks and music.

One program schedule shows that KYJ aired operatic soloists, a singing

comedian or saxophone artist, both from vaudeville; readings of

materials from editors of top magazines of the day; and even a talk by

the store's radio operator Charles Austin, "giving an authoritative

discourse on an interesting phase of radio receiving."

Southern California resident Jack Bascom of Glendora told me in a 1990

letter that when he was 13 or 14, he visited KYJ while they were on the

air. It was in mid-afternoon, and people in the store could watch

the KYJ broadcast through a window and listen to the broadcast over the

outside speakers. A few rows of chairs were placed on the other

side of the window for the visitors. On the same floor, customers could

look at the displays of radios and radio parts for sale.

In addition to the radio department on the 4th floor, the store also

had its own radio school. The subjects taught included classes in radio

theory, Morse code, how to become an amateur radio operator, etc.

KYJ, like other small short-lived stations that were broadcasting

during 1922 in Los Angeles, was well remembered by other "old-timers"

many years later. Wallace Wiggins was chief engineer and co-owner

of KREG/KVOE in Santa Ana in the 1930s and '40s, after working at KHJ

and KGFJ. In a 1974 oral history interview with Cal State

Fullerton, Wiggins remembered KYJ as one of the first stations he

listened to on a crystal set in 1922. George Farmer, W6OO, wrote

in his book "Radio Almanac", about picking up the KYJ signal aboard a

ship he worked on as a wireless operator in 1922. Adding to the

KYJ memories in later years, in 1950, Ed Stodel, owner and president of

Stodel Advertising Company in Los Angeles, talked about his early

interest in radio broadcasting. He told Broadcasting magazine

that he was 12 years old in 1922 and built his first crystal set.

Stodel remembered that when a radio station was off the air on certain

days, he used to telephone the Hamburger’s Department Store and request

that they put KYJ on the air, so he could hear their music.

Station owners in 1922 learned quickly that radio could be used to

discuss important issues. In early April of 1922, W. L. Pollard,

who was in charge of KYJ, told the Los Angeles Times he was giving a

half-hour of air time to an attorney opposed to a state bond measure on

the November 1922 California ballot. The April 6th talk went out on the

500 meter wavelength, which was allowed by a special permit from

Washington, instead of the usual 360 meters, from 9:00 to 9:30

p.m. Since then, local and national politics have filled

countless hours of radio air time.

One example of how a radio station's signal could travel quite far in

the un-crowded broadcast band in those days is a letter KYJ received in

mid-April, 1922. It was a reception report from a listener in

Halifax, Canada, more than 3,500 miles away! The Los Angeles

Times reported that the letter correctly quoted the names of the

phonograph records played on a March 24th broadcast. Owner Leo J.

Meyberg said, "Of course, this represents a freak result, particularly

as the station was operating at 5 watts and a radiation of 1.6

amperes. Atmospheric conditions must have been nearly perfect to

have made the reception at Halifax possible. However, we have received

similar reports from the Panama Canal Zone." An ad in the April

1, 1922 edition of the Times also indicated that KYJ's signal was

received in Honolulu!

The time-sharing agreements on 360 meters didn’t always work out in the

best way for listeners trying to hear a particular station at a certain

time. In the Los Angeles Times of July 27, 1922, the radio page

printed some letters from the 64 letters received from radio fans with

general complaints about local broadcasting stations. One Los

Angeles writer complained about interference caused by two stations on

the air at the same time on 360 meters. The writer didn’t think

anyone could tune his radio set to separate KLB Pasadena and KYJ Los

Angeles. T.M. Simpson wrote, “KLB got on the air about one minute

before KYJ and was doing fine and delivering a fine program, and

immediately KYJ came on, and from the sound of things, they must have

had a thousand watts on their tubes and that settled it. Then we

listened in to such announcements as the following: “Our next

offering will be a fox trot, “By the Silvery Nile” by the Isham Jones

Orchestra,” followed by “Our next selection will be “Blue Bird Land,” a

fox trot by the Isham Jones Orchestra.” Other letters also

complained about playing phonograph records over the air.

Four months later, the radio department of Hamburger’s Department Store

told the Evening Express newspaper about interference from other

stations. The radio page from November 8, 1922 started this

way: “Complaints have been received by the radio department that

broadcasting stations working off their scheduled time on 360 meters

last week, interfered with programs being broadcasted from KYJ.

Notices of this sort are repeated to the erring station with the

request that they keep the schedule agreed upon. If such

interference takes place again, KYJ would appreciate being notified at

once.”

By December of 1922, their final month on the air, KYJ was using mostly

live talent during all broadcasts. In Radio Doings of December 17

to 24, 1922, the KYJ program schedule indicated the station was on the

air 7 days a week from 6:45 to 7:30 p.m. Monday through

Saturday, KYJ was on the air 3 to 4 p.m. and some days from 3:30 to 5

p.m. There were several instrumental performers, mainly on

piano and violin. One evening, the entertainment was from a

saxophonist and a pianist, who offered “Jazz From the Great White

Way.” The next night, another jazz orchestra performed through

the courtesy of two songwriters. A song duo from vaudeville

appeared one night and a concert baritone from the Ambassador Theatre

in Los Angeles sang another evening. During the half hour from

4:30 to 5 p.m. on a Tuesday afternoon, the broadcast featured “A

reading of special radio articles by the associate editors of “Vogue,”

“Vanity Fair” and “House and Garden.” KYJ listeners also heard an

actress from the local theater reading extracts from a drama by Eugene

O’Neill, during a Thursday afternoon broadcast.

For various reasons, KYJ could not make a go of it, even though it

seemed to be popular with listeners of the day. Without commercials to

pay for operational costs, the sale of radio sets apparently was not

enough to keep the station on the air, or perhaps the owner lost

interest in the project. 2

On Friday, December 29, 1922, the Los Angeles Evening Express reported

that KYJ, the “Express-Hamburgers Radio Station,” would be going off

the air for good. The decision was made by the Leo J. Meyberg

Company, the owners of KYJ radio. A “goodbye program” was

broadcast on Saturday, December 30th, which included the playing of

“Taps.” The newspaper reported that the schedule for KYJ that day

included speeches by officials of the Hamburgers store and KYJ

announcers and engineers. KYJ’s final one-hour broadcast on 360

meters/833 kilocycles, took place on Sunday, December 31, 1922.

This 50-watt broadcasting pioneer that entertained early Los Angeles

crystal set and radio owners for approximately 14 months, signed off

for the very last time. Because the Evening Express did not

publish a paper on Sundays, there was no coverage of KYJ’s last

broadcast and I couldn’t find any mention of the ending of this radio

station in their Monday January 1, 1923 edition. It seems that

other Los Angeles newspapers also ignored the situation. I found

however, that the Evening Express radio schedule continued to list KYJ

times on the air for several days, after the station signed off for

good.

In the January 6, 1923 edition of Radio Doings, it was announced that

the Hamburger’s store had discontinued broadcasting. But the Leo

J. Meyberg Company, which owned and operated KYJ, was to broadcast from

their studio via phone line over KFI at a later date. KYJ's

station license was deleted by the Dept. of Commerce on May 1,

1923. Some of the information on the history of KYJ was gathered

from a December 1921 story in the magazine Radio News.

FOOTNOTES:

1 At

the same time, the Meyberg Company

operated station KDN in the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco.

2 A

possible reason for the closing of both KYJ and KDN in San Francisco

was the death of Sheldon Peterson, who was said to be the driving force

behind the stations. Mr. Meyberg, the company President, was primarily

interested in the sale of lighting fixtures and associated electrical

equipment. He had little real interest in the stations, and lost the

desire to operate them after Peterson's death.

|