|

This interview took place on Friday

afternoon, January 17, 1992 at Mr. McDowell’s home in Long Beach,

California. This is a slightly edited transcript of that

discussion. Such an interview is spontaneous in nature, so the

answers to the questions are recalled to the best of the interviewee’s

recollections. In the case of Mr. McDowell, many times I would

ask only one or two questions, and he would continue to talk, adding

new stories and information while reminiscing about what radio

broadcasting was like in the 1920s and ‘30s.

Background

Lawrence W. McDowell (1905-1997) was the original engineer for radio

station KFON (later KFOX and since 1977, KFRN) in Long Beach.

This interview came about thanks to help from Larry’s longtime friend,

George Riggins, who was a history writer for Radio World magazine at

the time. The interview tried to cover many aspects of what radio

broadcasting was like in those “pioneer days” at KFON, as well as his

early interest in electronics and radio.

Larry McDowell was born in 1905 in Cincinnati, Ohio and grew up in the

College Hill section of that city.

Questions were asked by Jim Hilliker (J) and George Riggins (G), with

answers given by Larry (L).

J: How did you get interested in radio

and electronics?

L: Well, I guess as far as I can remember, I was interested in

electronics from the day I could pick up a screwdriver. I made a

couple of little things when I was about 9-years-old. Three of us

decided to run a telephone line between our houses, which were about a

quarter of a mile apart. And I later went to work in an

electrical supplies store in downtown Cincinnati. You had to have a

work permit. I was probably 13-years-old. So, from there, one

thing led to another in electrical work, radio and what not. When

I started at the electrical supply company, I was an errand boy; the

janitor during the day. If there was any material (merchandise) to deliver, I would

deliver it, even by pushcart. If it was close by (the customer), I’d push the cart 5

to 6 blocks in downtown Cincinnati. If it was any further than that,

I’d get on the streetcar. (Editor’s

note: Here Larry talked about delivering rolls of wire and porcelain

fitting. Electricians used porcelain knobs and porcelain feed-through

tubes for the wires). Those were the days of open wires on

plugs (wall sockets), through

the various parts of buildings. They’d drill a hole and put a ceramic

tube through it, and so forth.

First Amateur License and

Working for Crosley

L: I lived in College Hill and the Crosleys lived there, and they

played tennis. And I used to play tennis when I was allowed to get on

the court, ‘cause I was little. My buddy’s folks owned the court, so,

we did that every once in a while, when they (Crosley’s family) were finished,

providing we cleaned it up and re-lined the dirt court. So, I got to

know him (Powel Crosley). I

hadn’t gotten my amateur (radio)

license yet, but he knew I fiddled around with electrical things. And

he said, “We’re going to start a radio manufacturing business.” They

were in the phonograph business; they actually just made the

cabinets. Somebody else put the machine in, because phonographs in

those days had wind-up motors and a tone arm, with a horn that

magnified the sound. So, he (Mr.

Crosley) said, “We’re going to start a factory and I know you

know something about wiring and that kind of thing. I’d like to hire

you, because we’re going to start a production line. I know Henry Ford,

so I went over there to see how he did it. I think I’m gonna set up a

factory down there to do the same thing. What I need is somebody that

can tell me what goes wrong with it (the completed radios if one fails

to work). What I need you to do is, after we hire all these girls, and

we’ll start out with this radio…” (Larry

continued talking about how the production line worked.)

L: It was a one-tube set, and the first girl would put the pieces

on (the chassis), then passed it on to the next one. And she’d put the

green wire and red wire on, and passed it on to the next one. And she’d

put the blue wire on, until it got to the end, and it was

finished. (He then continued

explaining the process in Powell Crosley’s words to him). “Then,

it (the radio) will go over

to you, and you test it out to see if it works. If it doesn’t work,

then you find out which girl put the wrong wire on! Go back to her and

tell me what she did wrong. And if she does it twice, she’s fired.”

And that’s the way it was. If she made two mistakes, she’s done. Get a

new one. They didn’t know what they were doing. All they knew was they

put the wires on, and if it got in the wrong place every once in a

while, I’d tell the girls, “You’ve got to put the red one where it

belongs, in this spot to that spot. Just don’t mix them up. If you get

it on the wrong one, and you put another one in its place, the whole

thing won’t work!” They didn’t know why. Anyway, I stayed there a

while, about 1920.

I was still in Cincinnati, so I got my first amateur license in 1921.

And I worked for (Powel)

Crosley a while doing the same thing. He had a radio station (which soon became WLW) out in

College Hill where I lived. It was either 50 watts or 100 watts and it

first operated under a ‘Z’ call I believe, and he was allowed to play

music and so forth on it. He decided to move it down to the factory,

and I gave him a little help doing it. He had a qualified engineer that

worked for him too. I really didn’t do too much with it, except that, I

sort of helped a little bit. I was still in the factory, inspecting the

radios coming off the production line. Then my folks decided to move

out of Cincinnati and come to California. So, Crosley moved his station

from his house to the factory. One hundred watts was pretty good power

way back then. And when I came out to California, I didn’t have any

further contact with what they (Crosley/WLW

radio) did until many years later. I went back and visited them

when they got up to 500,000 watts (1934-1939). (Editor’s note: WLW radio remains on the

air today at 700 kilohertz on the AM band, with 50,000 watts of power.

It was the only AM radio station in the United States ever to be

allowed to use more than 50,000 watts, on an experimental basis).

Arrival in

Los Angeles—1922

(Editor’s note: At this point

in the interview, Mr. McDowell proceeded to explain what happened when

he moved to Southern California and the various jobs he had, related to

the early radio industry).

L: When I came out here (Los Angeles), I still wanted to get into

anything to do with electricity. I got off the train downtown at the

old depot, and walked up Third Street to the Rosslyn Hotel, where my

folks were going to stay for the night. (Editor’s note: The actual address of this

hotel is 112 W. Fifth Street, not Third.) I walked down Third

Street and saw “Radio Supply Company” on the side of the street. This

was on a Sunday. I went back on Monday and said, “Do you need anything?

I’m looking for a job; just got in from Cincinnati.” And he said,

“Yeah, what do you know about electricity?” “Well, I worked in an

electrical supply company in Cincinnati, and at the end of the day, one

of my jobs was to put all the stock back on the shelves again. So, I

had to know all the parts, any kinds of switches, that kind of thing.”

So he said, “That’s fine. What do you know about radio?” “Well, I

was a radio amateur in Cincinnati, and I believe I could start a radio

supply outfit.” It (the store, Radio Supply Co.) was the same

kind of place I worked at and they didn’t have a radio department. So I

said, “I think I know something about it anyway.” I said, “I have

a whole trunk load of stuff I brought out with me.” And he said, “Good.

We’ll start out with that kind of stock.”

L: I had a spark transmitter, which was getting to be obsolete,

but I still put a spark transmitter on out here in California. But I

had a lot of other parts. Radio receiver parts, tube sockets that

Crosley made, and the book condensers (later

called capacitors) that were built like a book. It opened like

this (makes a motion with his hands),

and you changed the capacity with a wheel that turned in the middle of

it, and we had a bunch of those. (Editor’s note: The “book” tuning

condensers were invented by Hugo Gernsback and Crosley used them for

low-cost in his receivers. They had an adjusting screw that moved the

plates apart in the way a book opens.) Plus other things I

put on the shelf down there. I said we ought to get more stuff. There

was a salesman I got some radio gear from, who came by every so often.

We put up a pretty good-sized store in there. I don’t know if you’ve

ever seen one of those old Magnavox loudspeakers. He had one of those (horn) speakers, and we took that

one. It was so hard to get radio parts out here in California, there

was nothing out here to buy. So we put that (Magnavox loudspeaker) up

there for sale, and we sold that three or four times before anybody

ever took it! Somebody would buy it, they came back a day or two, and

someone else would say, “I’d love to have that,” and we’d raise the

price a few bucks and sell it to the new guy. That damn speaker sold

for so long, I thought it was going to wear the damn thing out before

somebody really took it away. I still remember that old Magnavox horn.

But it was a pretty good horn; it was a good loud horn. It had a

permanent magnet. They hadn’t yet put the electromagnet in the base of

it. Later they did.

Second Job in Los Angeles

L: So I stayed mostly around the fringes of radio. I decided to

get a different kind of job. So this place on Pico (Brodie Electric)

made storage batteries and winding armatures. Well, I hadn’t learned

how to wind an armature yet, so I said I ought to learn how to do that.

I also took a machine shop course. So, I went over and they said,

“We’ll teach you how to wind armatures.” So, I started learning that. (He explains how they were wound).

Put wire around, pound it down. It wasn’t insulated wire and if you

weren’t careful, you’d cross the wires and short them out, and that’s

the end of that. They then decided they wanted to get into the

radio business. They said, “What do you know about that?” I told them.

They said fine. “Do you think you could design a crystal radio that we

could sell?” They were still selling crystal radios in 1923. I said,

“Sure.” So I designed one, and they said, “How are we going to build

this thing?” I said, “Well, when I worked with Crosley, we had a

production line. We hired these girls and we ought to have about four

of them to build the crystal set. And at the end, I test it and see if

it works.” So, we set up another production line. And that went

on for a while and I guess I got tired of that. I sold for a while and

I designed a radio for another outfit, but it was unsuccessful. (Larry went on to explain the next job).

Radio was so new then, that they (Radio

Supply Company) had a storefront on Main Street in downtown

L.A. And my job was, to start out at the desk in the window with

part of an assembled set, and start putting the radio together, so

people would gather outside the window and start to watch me. And then,

I had a loudspeaker on the outside of the window, and after I put it

together, I turned it on. And you’d just see a bunch of parts in front

of me to start with. I’d gradually put it together, turn it on, tune in

a station, and music would come out of the front (outside). That was my

manufacturing business. I always stayed in the electronics field,

though.

Taking Radiotelegraph Exams

L: Being close to radio, I knew there was some commercial stuff

from people. I knew you had to have a commercial license to operate a

broadcasting station. So, I decided to study a little bit. I went down

to the YMCA in 1922, I guess. (Editor’s

note: The YMCA in downtown Los Angeles ran a radio school in those

days.) The exam for a Second Class radiotelegraph license.

So I kept going, and in a week or two, took the exam for First Class

radiotelegraph license. I had no experience in commercial telegraphy or

broadcasting. What little I did was with (Powell) Crosley. The YMCA in

L.A. was the examining location. They did exams for the Department of

Commerce and radio inspectors would come up there. There was also a

hiring hall there. So, I got to know a few of the guys and they were

all ex-marine operators. And that’s the only thing there was, either

that or amateurs. So, I applied for a job at this hiring hall. They

said, “Well, we’ve got a commercial ship that needs a wireless

operator.” And I’d never been on a boat before. So they said, “Go on

down to the harbor, they’ll be shovin’ off shortly.” I went down and

said, “Here I am. I’m your new wireless operator!” They only had one.

This was a quenched gap, 500-cycle transmitter. And it was a freighter

and it left in November. I could see why the other guy got off. In San

Francisco, it was okay. But when we left San Francisco, we ran into a

blizzard gale. There was no heat in my cabin. Except when I changed the

batteries, the resistors got hot. So, I left the door open and this

storm hit that night. And I woke up the next morning and my stateroom

floor had a coat of ice on it. And the bulkhead where the door was open

had a half-inch of ice on it, and it was colder than hell inside

(laughter). And so, I made it back to Los Angeles and said, “I don’t

think much of this wireless operator kind of business.” I went back to

the YMCA and looked for another job.

Beginning of

Radio Station KFON

L: They said, “Well, there’s a guy in Long Beach that needs an

operator and somebody to be able to put a broadcasting station

together. He’s got a license (for the station), but the guy that

started to build it quit.” And the work wasn’t finished yet. And,

when you’re that young, you can do anything. I had done enough things.

I’d already put together an amateur radio station. I got out of the

spark business and I put together a tube transmitter, so I had a little

experience in tube transmitters and so forth. Amateurs didn’t run

radiotelephone in the early days, only code, but I still knew how to do

it. I had read a little bit about it. Gernsback, remember Gernsback?

Gernsback was the manual that all the hams read. It was quite a book to

learn from.

J: He also had the Broadcast News magazine (in the ‘20s).

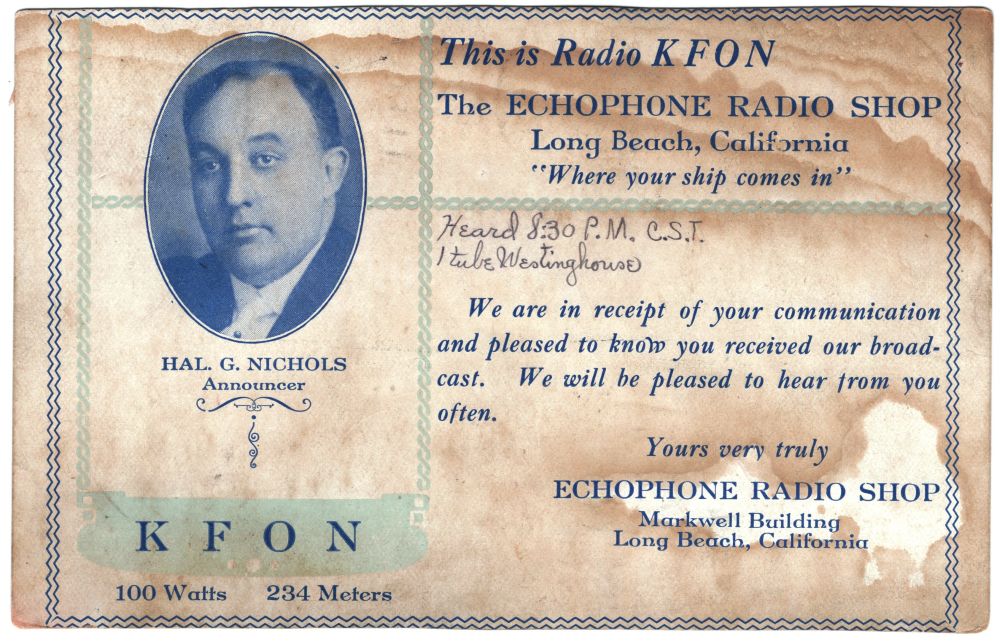

L: I think so. So, they sent me down to Long Beach and I

went to see Hal Nichols and his brother who had the license for this

station, KFON. And their business was selling Echophone radios. They

asked me what I could do. I told them. And I figured I could finish

building this station; that was no big problem. It was only going to be

100 watts and I could do that all right. They were not radio people.

They were musicians. Hal was a fiddle player and his brother Earl was a

piano player and played the piano and xylophone. And they came out from

Denver, and in Denver they had a radio station built by this same guy

(the engineer who quit) from Wyoming. It (KDZQ) was about 10 watts, I

think. And they played every night and broadcast on this radio station.

That was all that was on it, just the dance band in Denver. And they

decided to come to California. They just closed down the dance hall,

closed down the radio station and took off. They didn’t sell it.

Couldn’t sell it anyway. And when they got here, they started a dance

hall on the Silver Spray Pier and off the Pike. It was a real nice

dance hall down there.

And then, they decided to do like they did in Denver. They had another

guy that was a friend of Earl’s (Mr. W.H. Warinner) who was the auto

agency for all the cars the army needed during World War I. Made a

fortune; made himself very wealthy. He knew Hal and Earl and he said,

“I’ve got a friend in Chicago who owns the Echophone Radio

Manufacturing Company. Why don’t we start a distributorship in Long

Beach? I can get the distributorship for Southern California.” So he

did, and they rented some space in the Markwell Building (Editor’s

note: Location of building was on Seaside Ave. at the end of the Pike.

Studio/offices on mezzanine floor, address 27 Arcade, Markwell Building

for KFON/Echophone Radio Shop. Transmitter and antenna were on the

roof). And Hal said, “We’ll do like we did with our dance hall and get

a broadcasting station.” They just applied for it (the license). There

wasn’t any problem getting one, you know. It was easy to get one. So,

they got their license and this guy that put the other one on in

Denver, he quit and went back to Wyoming. That’s when they (YMCA Radio

School) sent me down to finish putting it together.

(Editor’s note: The

Markwell Building was later called the Jergins Trust Building. It

was located on Ocean Blvd. at Pine Street. The building was

constructed in 1919 and was demolished in 1988. KFON radio was

inside this building from 1924 until the end of 1928. The

transmitter and antenna were on the roof of the building. The

studio was on the second floor.)

J: What did that entail?

L: Well, it was partly there, and a lot of the parts were there,

but…they had a lot to do on it yet. So, I finished putting it together

and got it on the air. And it’s been there ever since.

(Editor’s note: KFON’s first

broadcast was at 8:00 p.m., on the night of Wednesday, March 5, 1924.

The program began with an address by the Long Beach Press Sunday

editor, Frank P. Goss, since the Press and KFON apparently had made a

deal to promote the station’s broadcasts in the newspaper, and the

Press would do newscasts on the new station. Goss would later become

the newscaster for KFON. A speech was also given by Long Beach Mayor

C.A. Buffum, extending the city’s greetings to radio listeners. Musical

entertainment was also broadcast from KFON that night, from several

Long Beach singers and musicians. One highlight was a cornet solo from

Herbert L. Clarke. Clarke had been a soloist with John Philip Sousa’s

band, and was now director of the Long Beach Municipal Band).

Some

Technical Details Regarding KFON

L: It was a hundred (100) watts (transmitter power) and we had,

of course, vacuum tubes. They hadn’t yet invented the AC filament. The

AC filament wasn’t invented for many years later. It lit up off of the

DC, which meant they had batteries (to run the station equipment and

transmitter). And at the radio shop down below (on the second floor),

we sold these radios. I didn’t do anything with the radios. I was

strictly with the broadcasting station. They used batteries to light

the filaments and “B” batteries. Well, I had to build an amplifier for

this station and we didn’t want any “B” batteries like they used for

the radio, ‘cause they didn’t last too long. So, we’d get a whole bank

of 135 volts of 2-volt cells. They were about as big as…well, a little

bit smaller than a mason jar. We had them lined up to make our 135

volts and a couple of big storage batteries to light the filaments (of

the tubes).

Using KFON to Sell Radios

L: One thing led to another. We didn’t operate this station

(KFON) all day long.

(Editor’s note: The station, in

its early days, was on and off the air about two or three times a day.

By March 14, 1924, KFON had an evening concert broadcast at 8 p.m.,

plus a luncheon broadcast from 11:30 to 12:30 and a dinner program from

5:45 to 6:30. The station was off the air the rest of the

day. At this point in the interview, Larry McDowell explained what

happened when KFON was not broadcasting regular programs).

L: A salesman would go out to demonstrate these Echophone radios

to somebody. And he’d call back in and say, “Larry, how about turning

the station on and play a record or two and dedicate it to Mrs. Jones,

who we’re selling this Echophone radio to.” So we did, and I’d say,

“Mrs. Jones, we hope you enjoy this radio; this Echophone’s a great

set!” I didn’t do that; Hal did that, okay? And the salesman

would maybe make his sale and come back in. And (laughter), I’d turn

the station off. We didn’t run it all day long.

I don’t know how often we turned it on. I know we didn’t turn it on in

the morning very often, because there was nobody listening anyway.

There were a few people who would listen then, actually, but there were

no commercial stations, you know. I say “commercial stations.” I mean

other than people that were advertising what they owned. We owned the

Echophone distribution company, so we called it “The Echophone Radio

Station.” KFWB was owned by Warner Brothers (to promote their movies),

and KFI was owned by Earle C. Anthony (Packard auto dealer), and KHJ

was owned by the L.A. Times, and you know, down the line. But, that’s

all they advertised. You really didn’t hear anything else on those

stations except what they sold. And we didn’t have anything on our

station except Echophone radios (to sell). Hal’s cousin and this friend

of his owned a little candy shop around the corner. I don’t think we

even mentioned that! Well, we never thought about putting a commercial

on the radio and advertising, except for something you owned, I guess.

Early Remote

Broadcasting

L: I wasn’t an announcer. That wasn’t what I was hired for. I was

the engineer. We didn’t call them engineers then. We called them

“technicians.” I had a first class license, which qualified me for

anything in the broadcast business, I guess. Although the examination

didn’t ask you one damn thing about broadcasting (laughter)! But now, I

had the license that qualified me to do this. But, we decided to

broadcast the Long Beach Municipal Band, which was across, where the

Pike ended really, at Pine Avenue, but there was Seaside Boulevard a

lot further east. And there was a wooden auditorium across the street.

And the Long Beach Municipal Band used to play there in the afternoon.

So I ran a wire across the street to the band, and hung a microphone up

from the ceiling.

(Editor’s note: It was on March

18, 1924 that this work took place. A story in the March 19, 1924 Long

Beach Press stated that KFON could not go “on the air” the night

before. The station was partially dismantled while a microphone was

installed in the Municipal Auditorium to broadcast the concerts of the

Municipal band. The story went on to explain that electricians didn’t

get their wires installed in time to permit operation of the station

that night.)

L: This old wooden building had just tremendous acoustics! Even better

than the one they built later on. There were all kinds of

reverberations in the one they built later on. But this old wooden

building, that band picked up on a single microphone just like you were

listening to it there! So, Hal didn’t want to do the announcing on it.

He was working on selling Echophone radios. And Earl was sort of a

mechanically inclined guy and he would put them together and what not.

So, they said, “You’re going to announce the band.” The station

(transmitter) was up on the roof, five floors up, and the studio was

down on the second floor, which was an arcade with a balcony around it.

So, I went up to the bandleader and say, “I’m going to broadcast the

band today. What’s the program?” And he’d give me this list, and I’d

look at it, and I’d go back and say, “We’re broadcasting the Long Beach

Municipal Band under the direction of Herbert L. Clarke”, I think it

was. (Editor’s note: It was! The

1925 program listings in radio magazines and newspapers of the day list

Clarke as director of that band.) “And the first number’s going

to be…” and I’d look at it (title of

musical piece) and say something. (Laughter) Whatever it was, and I’d

do that for a little while. And people would call up (the radio station) and say, “Does

that guy know what he’s saying?” So, I blabbered through it. A little

bit later on, I went to see the bandleader and looked down the list (of tunes) and I’d say, “How do you

pronounce that one?” And he’d tell me and I’d make a little note over

it. So, pretty soon, I got so good that it didn’t sound so bad. They (the titles of musical pieces and

composer’s names) were pretty much like they should’ve sounded.

But my total announcing experience was very limited. And we went along

like that for a while. Then we finally broadcast (remotes) from a couple of other

places close by. Any place that I could run a microphone to, that I

could do without any amplification or anything like that was fine. I

hadn’t learned about amplifiers or remote lines yet. We decided to

broadcast from a dance hall downtown in the afternoon, and we ran a

line, just an open microphone, no shielded line. Then, there was

another place up the other way. It had a ‘follies’ type of thing, with

girls dancing on the stage, and we had that thing later on.

More 1920s Memories of KFON

L: The Echophone Radio Company started to fail. It wasn’t worth a

damn anyway. We finally came out with a loop antenna. It was supposedly

good, but they had to put an amplifier on it. It (the radio) had a horn (speaker) that went with it. It was

a wooden kind of horn…through the back of it, and if you were in a room

like this (Larry talking about his

living room) with nobody talking, you could hear it (the radio) pretty good. What we

played for our records (over the

radio station) wasn’t much better. There was no…nobody had

developed a motor-driven turntable yet. It (the phonograph) was a crank-up

kind. That’s what we had in 1924. And they hadn’t built an amplifier

for the tone arm. The tone arm was just a diaphragm that went into the

arm that fit into a box that had amplifying characteristics from its

design. If you’ve seen one of those phonographs in those antique

places…wind-up arm and a…well, that’s what we used to use to broadcast

records. And Hal would go down and meet with the announcer, wind

the thing up, put the thing on, and put the microphone into it (the speaker). (Laughter) And it

did pretty good, I mean if nobody made any noise in the studio. Later

on, they came out with the first motor-driven turntable that we had. It

had a little motor with a wheel on the side of it, and laid it on the

rim of the turntable. And that turned the turntable to speed; all the

records were 78 RPM. We just had one speed. But, that did away with the

winding part of it. But nobody had come out with a magnetic pickup yet,

when we were doin’ that. We still had the microphone in front of the

horn. But we now had the motor and we didn’t have to wind it any more.

So, those were pretty amateurish kind of days, but…I don’t know what

some of the other stations were doing; I don’t think many of them did

much different. I think a lot of us learned (broadcasting) from things that we

would talk to other…Most of us in the operating side were…either came

from aboard ships or were amateurs. There wasn’t any other training

around for them. I suppose Westinghouse might have. I don’t know. I

know Crosley didn’t. All he had was a qualified graduate electrical

engineer, and he didn’t know anything much about radio broadcasting.

And I know all the people I talked to were either radio amateurs…A few

of them had gotten into voice transmissions, but most of them were

still doing code.

J: It was all pretty new, even for the people that got into

announcing. A lot of them, I’ve read, started out as singers.

L: Well, if they had a good voice, sometimes they did. A lot of

them got into the broadcasting business by some other thing that they

could do, or they might’ve had a voice that sounded good.

KFON

Broadcasts a Wedding

L: In the middle of this transition from other amateurish things

that I was doing, I was going around with a young lady, and it was

1924. I was about 19-years-old, I guess. And Hal said “Why don’t you

and your girlfriend get married, and we’ll broadcast it!” All

right. So, we decided to do this, and we’d get married and we set the

date. I didn’t know anybody in Long Beach. Both of us came from Los

Angeles. She came from Texas and I came from Ohio. So she brought her

sister down to be the maid of honor. I knew Hal’s friend who sold

popcorn in the candy shop downstairs. I said, “I know Bill. I’ll get

him for best man, and Hal, his cousin, can do the rest of it.” So

we got the preacher and got the wedding all set. We had the studio on

the second floor. It wasn’t very big; about as big as this room. And

the transmitter was on the fifth floor. And I thought, I’m getting

married. Somebody’s going to have to be there to run it. So, I got a

friend of mine that didn’t know anything about vacuum tube

transmitters. I’m not even sure if he had a license. Anyway, I told him

what I was going to do and would he come down and stay with the

transmitter when we got married. Fine, so we got set to be married. The

preacher was set, and I think Hal and Earl played the music, whatever

it was, because we didn’t have any band and we weren’t playing records.

Anyway, about that time, the phone rings, and the guy on the roof says,

“There’s something wrong with the transmitter!” He said “Something’s

not right up here.” I said, “What do you mean?” “Well, it isn’t

working.” I said,“Well, the wedding’s about to commence! Okay, stand by

a minute, I’ve got to go up and fix the transmitter!” I ran up to the

fifth floor and went to see what was wrong with it. A tube was burned

out. A very minor thing, except it wasn’t working. So, I fixed it and

turned it on to see if I could hear the voices downstairs. I said,

“Everything’s okay now. I’m going down and get married! Don’t call me

if you don’t have to.” (Laughter) So,

I went down to the second floor and got married, and that was that. Got

in my car, took a little ride around town, and that was it. I didn’t

have any idea of going on a honeymoon. Heck, I didn’t get any time off

anyway. Had to go to work the next day.

(Editor’s note: The

wedding of Lawrence McDowell, Chief Radio Operator for KFON, to Miss

Vera Mabel Lee was broadcast on KFON at 8:30 p.m. on Wednesday night,

August 27, 1924. The Long Beach Press ran stories about the

“radio wedding” in the August 27 and August 28, 1924 editions of the

paper, along with two photos.)

J: How’d the listeners react to that, or did they care?

L: They didn’t care. (Laughter)

They didn’t even pay attention to it. You really didn’t have a lot of

listeners. This was in the evening and there were other stations on.

You had these big stations, well they weren’t “big” stations. KFI was

only 500 watts. That was big power then. It wasn’t that much of a deal.

J: Were you guys friendly with the other broadcasters? Was there

any competition or jealousy?

L: No. I knew some of them, only because they were hams or

ex-wireless operators. But, other than that, we didn’t have any

connection or any relationship with them. Most of them didn’t, except

the radio operators knew each other, because many of them were off of

the same ship or had been on the same line, or had an amateur station

and would talk to each other. Other than that, there was really no

connection between the radio stations. And none of us had any

commercials on.

First Commercial Message on KFON

J: What year do you remember the first commercial on KFON?

L: Well, we called KFON the Echophone Radio Station, but now that

was gone. There wasn’t much else around. Our first real commercial,

other than what we were selling (1924/25) was for a tailor shop on Pine

Avenue. He used to listen to us and he’d walk down to visit people in

the arcade. I think he knew another tailor (nearby). He’d go into the station

and see Hal and talk to him. He said, one day, “I listen to your

station whenever you turn it on. And it comes in great up at my

store.” Well, it should. It was only five blocks away! (Laughter) “I tune in all the

time and listen to the band when they’re playing. Why don’t you mention

my tailor shop sometime?” And he said, “I’ll make you, Hal and Earl a

suit of clothes. I won’t make it in my tailor shop on Pine Avenue. But

I own one in Beverly Hills, which is a “high-class” tailor shop. We’ll

get your measurements and my tailor will have a suit of clothes made

for you. We’ll send them down to the Pine Avenue shop and you can pick

them up.” So, we did and we got the three suits of clothes, and that’s

the first thing we got (commercial) other

than what we were selling (radios).

(Editor’s note: This was likely

Sam Abrams. In early 1926, the KFON program schedules list a one-hour

block of time, Wednesday’s from 9:00 until 10:00 p.m., “presented

courtesy of Sam Abrams. The Sign of Good Tailoring.” This was obviously

a commercial plug for his business over the air. It’s unknown if Mr.

Abrams paid KFON any money for announcements about his business, but

this was obviously the infancy of radio advertising. This may have been

in trade for the suits he made for the KFON staff. Another KFON

schedule for September 26, 1925 lists “The Markwell Saltwater Taffy

Shop program” from 7-7:30 p.m. This may have preceded the commercial

message for the tailor shop and also clears up Larry McDowell’s earlier

remarks about whether or not a candy shop in the Markwell Building was

ever mentioned on the radio station to promote the business).

More Advertising on KFON More Advertising on KFON

L: Then we said, we’ve got this radio station and maybe we can

get some money somewhere. We heard these other stations call themselves

by a name. We couldn’t call ourselves the Echophone Radio Station

anymore. But, we got in touch with a grocery store chain still in

business back east, called Piggly Wiggly Grocery Store chain. They

decided to come out to California. They said, “You don’t have a

name for your radio station. How about calling it “The Piggly Wiggly

Station”, and we’ll pay cash money for it (mentioning the store on the air to

advertise what’s for sale, promote the business and increase the number

of customers).” That was the first cash money we got from

anybody. Later, when they moved out of California, Piggly Wiggly was no

longer interested in advertising here. We (KFON) got acquainted with the

Hancock Oil Company. And the owner said to us, “Why not call it ‘The

Hancock Oil Company Station’?” So, we sold them the name, and that went

on for a number of years.

(Editor’s note: The Piggly

Wiggly Western States Company franchise operated more than 200 of their

self-service grocery stores in Southern California by 1928. In

1929, the Piggly Wiggly stores in California were acquired by Safeway

Stores, Inc. Today, Piggly Wiggly stores still operate in 17

states, mostly in the southeastern United States).

Call Letter

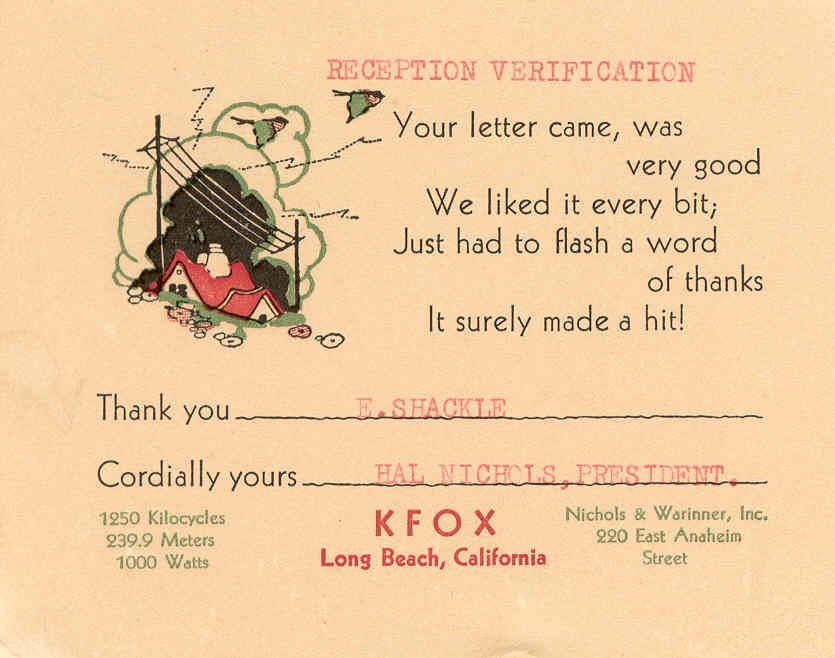

Change to KFOX

(Editor’s note: The call

letters for Long Beach station KFON changed to KFOX at midnight,

December 30, 1928. The first full day as KFOX was on December 31,

1928).

L: KFON, (the call letters),

that was just assigned to us (randomly)

by the U.S. Department of Commerce. But we got connected

with the (William) Fox Movie

Studio in Hollywood. (Editor’s note:

A story in the Long Beach Press-Telegram on December 30, 1928 reported

that the owners of KFON changed the station call letters to KFOX

because of a new alliance between the Fox Film and vaudeville

interests.)

And we had a pretty good deal going. Somebody said we’ll call ourselves

the ‘Fox Station’, but how about changing the call letters to KFOX?

That sounded pretty good, so we changed the call letters to KFOX and

opened an office and studio at Sunset Boulevard and Western. Everything

was going fine, but then the Fox Studio went bankrupt. So, we already

had our call letters, which weren’t too bad. And it would be quite a

job to change them again, so why change them? KFOX sounded just as good

as KFON. But we no longer had Fox, so we didn’t try to sell the name of

the station (to tie in with the Fox

Studio). So, by that time, we sold advertising, which had become

a routine kind of thing on radio by then. Radio stations selling

commercial advertising to people wanting to sell products. But, ours

sort of crept in accidentally. How it got into other stations, I don’t

know.

Station Slogan

J: How did the station slogan “Where Your Ship Comes In” get

started?

L: Well, we thought that was good because we did have ships

coming into the harbor here. And being on the harbor, we thought it

would sound, (he pauses for a moment

and thinks). We had a whistle we’d blow (on the air) for “Where Your Ship

Comes In.” We had a, what do you call it, a wooden horn. We blew it,

you know, in your mouth. And it sounded like a ship’s whistle. So, it

was something that sounded good. We hadn’t started commercializing all

this other stuff yet. “Where Your Ship Comes In” sounded good. Nobody

else could say that, because their stations weren’t on the coast.

J: I just noticed this from the August 1928 KFON schedule in

Radio Doings magazine. It also says the “Piggly Wiggly Station” under

“Where Your Ship Comes In.”

(Editor’s note: In doing more

research on KFON history, I found the origin of the slogan in the March

9, 1924 edition of the Long Beach Press on the front page of the paper!

This was four days after KFON had its first broadcast. There was a

contest sponsored by KFON and The Press. More than 4,000 cards

and letters were sent in, with ideas on what slogan should be used by

the radio station. The judges of the contest were KFON owner and

station manager Hal G. Nichols, W.E. Montfort, city editor of The Press

and Squire F. DuRee, city superintendent of recreation. The winning

slogan announced the night of March 8, 1924 was “LONG BEACH,

CALIFORNIA, WHERE YOUR SHIP COMES IN.” Maurice Selberg of Wilmington,

Calif. thought of the slogan. For this, he was awarded a three-tube,

model A Echophone receiving set (radio), offered by Hal Nichols of the

Echophone Radio Shop, in the Markwell Building. The article said the

radio has a “one-tube detector and two stages of amplification and has

a value of $135.” Announcement of the award was made on KFON on Monday,

March 10, 1924 during the broadcast of The Press program. The story

also states that the double meaning of the KFON slogan won the

appreciation of the judges. It indicated the port phase of Long Beach

development and the opportunity and promise of ease and contentment so

commonly expressed in the term “where your ship comes in.” So,

Larry McDowell’s memories of the KFON slogan indicate it was used quite

often, likely during station identification announcements, along with a

ship’s whistle. The story from the March 9, 1924 Press went into

greater detail as to how and why a slogan was chosen for KFON.

After the station became KFOX, the slogan was apparently still used as

late as 1938.)

First

Microphone Line Amplifier

for Remotes

L: No. I built some mobile equipment and amplifiers up

until, I

guess, 1940. Being a ham, I probably had more shortwave mobile

equipment (for remotes away from the

main studio) than most stations had. But, we had the station

that we built at 100-watts. Everything was “home brew”. (Editor’s note: This is a ham radio term

for all the equipment built from scratch by the technician.)

There was nothing you could buy; only transformers and other parts.

There were some (transmitters)

built; I think one (station)

in Los Angeles bought one. But, when we started putting advertising on

KFON, the Western Electric Company came down and said, “This is a

commercial radio station.” The fee was $500 for commercial use of a

station. I said, “We could’ve built five stations for that!” He said we

had to have a license, so okay. We were then getting into the

advertising business and getting a little money, and so we decided to

buy some equipment. So we bought a new 500-watt Western Electric

transmitter. That was at the same building downtown. We put up a couple

of towers in the meantime, and an antenna (made of wire) strung between

them. The first one (transmitting

antenna) was a couple of pipes with some guy wires on them.

G: Why don’t you tell Jim the story about the line amplifier you

built?

L: Okay. Having a First Class Telegraph license, I’m now an

expert in radio. But, I didn’t know nothing about broadcasting! I knew

from the ham stations that used voice into the microphone how that

worked. So, this preacher who married us thought it would be a nice

idea to broadcast the church services with a live choir, and they had a

beautiful organ. And it was one of these churches designed very

intricately inside. And they’ve never torn it down. It’s an historical

landmark. (Editor’s note: This may

have been First Church of Christ Scientist.) The acoustics were

excellent and the reverberation was nil. So I called the telephone

company and said, “I’m going to broadcast this church.” I’d already run

a bare microphone to the auditorium across the street and the Dudley

Ballroom down about a block. I couldn’t run a line to the church,

because it was four or five blocks away. So I told the chief engineer

of the telephone company that I want a line over to this church, but I

don’t want it going through any switches. So he said we’ll jump it

across the main terminal board and through the other end, and I said

fine. So, I hooked the line up to this church. I put the microphone on

the thing and a transformer. Two wires going to the station and a

ground. And I went back to the station, turned it on, and it was very

noisy! So I called the chief engineer at the phone company and said,

“This is a very noisy line. Can’t you give me another one?” So he gave

me another line and I told him not to run it through the switchboard.

It was just as bad as ever. So, I went to Los Angeles and talked to the

chief engineer of KNX or KMPC. (Editor’s

note: KMPC didn’t go on the air broadcasting until 1927, first as KRLO.

So it was likely the engineer at KNX Mr. McDowell spoke to that day.)

I said, “You broadcast stuff over phone lines. I’ve been trying that in

Long Beach, and the phone company engineer there can’t give me a quiet

line. How do you get a quiet line here?” And he said, “Well, we don’t

worry about that. You see that box? That’s an amplifier in that box.

Self-contained amplifier. It has a battery, 135 volts on the plate and

a couple of dry cells. You hook the microphone into that, then that

goes into the (phone) line

and that (amplifier) will

override any noise.”

L: So, I went down to Long Beach. I knew how to build an

amplifier. But, he had his self-contained in that box. I knew I had to

have “B” batteries to light the filament. After I had the storage

battery, I plugged it in there. Put the “B” battery plugged in there

and the microphone plugged in. So, I took it over to the church for the

broadcast. I put the microphone up on the pulpit and the batteries in

the amplifier, and put it all down under the altar. So, I pushed that

back a ways, and ran a telephone line to the terminal board. I went to

the station and the test (of the

audio) sounded fine now. So we got ready to broadcast the

service that Sunday. I had to turn it all on ahead of time, since I’m

the technician. So I’d turn it on, go back to the station, wait for the

preacher to start, and I got back to the church. And I noticed the

batteries were going dead for the amplifier. So I had to change the

storage battery while the preacher talked! I didn’t think about the

choir back here (behind me).

So, I was crawling across the floor, pushing the battery across to

change it and he was starting to preach. Those kids in the choir could

hardly keep from giggling, watching me. I went to the station and

dragged a new one back. I changed the battery, and the choir, music and

preacher were broadcast fine. After that, I learned to put the

equipment off to the side. I didn’t think about charging the batteries

after each time it was used, which is probably what the engineer in Los

Angeles did. I built a lot of mobile equipment (for broadcasting) after that and I

was prepared.

J: Was it a big deal going to 1,000 watts?

Move to

Anaheim Street

L: We moved to Anaheim Street because

we decided we could make a

deal with the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company to build a studio on top

of their building (220 East Anaheim

Street). And if we moved the transmitter out there, they would

build the studio and office for us on the top of their building. Then,

they would get some advertising out of it. So, then we decided to

increase our power to 1,000 watts. And we had the 500-watt station at

the Jergins Trust Building. To finance the new station (higher-powered transmitter and other

studio equipment) we made a deal with the First Church of Christ

Scientist. In return, we agreed to broadcast their church services for

buying our equipment (one-year

agreement).

Now, we’re out on Anaheim Street and the transmitter is ready to go. I

did a lot of the installation work. Western Electric sent an engineer

to supervise. The church service was the first broadcast on the new

station. It started at 8 o’clock at night. I had an operator at the

station at the Jergins Trust Building and I was at the other one on

Anaheim Street. The announcer downtown said: “This is KFOX from the

Jergins Trust Building in downtown Long Beach. This station is signing

off, and we’re now transferring to our new station on Anaheim Street.”

So they turned the station off and we turned the (new) station on. “This is KFOX

from Anaheim Street. Now, we’re going to broadcast the First Church of

Christ Scientist, the first broadcast from this new equipment.” By that

time, the oil company (Hancock)

was involved with it. We did pretty good. We made money. We did a lot

of live broadcasting (music,

singers, live plays, dramas, comedy, variety shows, etc.). We

had two writers, six or eight directors, some doubled as announcers.

One doubled as a salesman and they were on almost all day, so we had

more technicians working.

KFOX Coverage of the 1933 Long

Beach Earthquake

L: We weren’t in this building very long, a couple of years, and

the earthquake hit Long Beach. (Editor’s

note: The quake hit on March 10, 1933 at 5:54 p.m.) We were on

the second floor and the (antenna)

towers we built were self-supporting. The main tower went down to a

concrete block about 8-feet thick and 14-feet square. We had to build

the base of that tower so big, so it would spread enough to straddle

the entrance to a work bay for big trucks. The entrance was about two

stories high. Tower at the back end was fine by itself, normal size.

They serviced large trucks there, not passenger cars. The antennas were

pretty solid, but the building was constructed when the city didn’t

watch closely where the cement company got sand, and some had salt in

it from the beach. After a few years, the bricks got soft. The rest saw

this lousy cement fail and bricks and the wall fell down. Us and a lot

of stations were still using generators; no power supplies yet with

high voltage and transformers. Here’s a 2,000-volt generator and we had

to clean it every day to keep the arc from going around the armature.

Otherwise, it would burn itself out. We’d clean it. So, this brick

wall, cement, and dust fell all over the generator.

I had just left the station for home, four to five blocks away, when

the earthquake hit. I was eating dinner. I rushed back to the station.

Of course, everything was dark. The power was off. I looked in and said

“My God!” I thought the transmitter was caved in. Records were all over

the place. Everything was in a shambles. I said to one of the guys (a staff announcer for KFOX), “If

you want to go up and help me, fine. I’m going to get all those bricks

off of there. Let’s see if we can get this generator uncovered and see

if anything’s wrong with it.” We cleaned all the bricks off and

used a flashlight to blow the dust out of the generator. I was one of

the owners now and I felt we’d better get this thing back on again. Got

it cleaned off and turned it by hand. Then, I was just hoping the tubes

in the transmitter weren’t damaged. I looked inside, and the tubes were

all right. They were water-cooled and I had spare tubes in the back

where the generator was. But I hadn’t looked to see if they were all

right. They were mounted on a cupboard. It looked clean; nothing on top

of the high-voltage condenser that I could see. One of the announcers

showed up then, and I said, “I don’t think we can broadcast from the

studio. You take a look and see.” So, we took a microphone cord and

broadcast from down the alley. I said, “You’re out on the roof. You

don’t have to come in if you don’t want to.” About 10:00 p.m., the

juice (electricity) came back

on! So I said, okay, I’m going to turn it on easy and see what happens

with the generators. You know, high-voltage generators, they have a lot

of dust around them, and if they start to arc, that’s the end of it!

And I didn’t want that. Because if that happens, I thought we’re stuck

for a long time. I guess I cleaned it pretty good. It didn’t arc. I hit

the switch on the transmitter for the power to come on. And the antenna

meter read where it belonged, the tubes all lit and all the rest of the

meters. We had fifteen meters on the transmitter that had to be logged

every half-hour! They all looked like where they belonged and I said I

guess we’re in business.

So, I got the announcer down below to talk. KFOX, back on the air

again! We didn’t have any commercials anyway, since business was so

bad. I don’t think we had half-a-dozen accounts on. We had a few that

paid permanently. Business was so bad (during

the Depression) that before the quake, I spoke with Hal (Nichols). I took care of the

money. He was still a musician. He liked to announce and play his

violin and be in the various plays. I told him, “We have a few thousand

dollars in the bank. I think you’d better call everybody in and suggest

we have everyone take a 25% cut in pay.” He said, “I’m willing, if

you’re willing.” I said, “You and I probably won’t take home any pay

for at least six months.” The station owed it to us, but we

didn’t take it, so we could pay the rest of the staff. So we told

everyone, “You know what business is like.” Everybody took the 25% pay

cut and nobody quit.

Back to the earthquake. There was no radio communication in police cars

at that time, for the most part. So, we mainly turned the station over

to let fire and police dispatch whatever was necessary for the

earthquake emergency. We didn’t have one word of commercials for three

days. They had declared martial law in Long Beach. Armed guards stayed

at the front and back of the station. They camped there in the parking

lot and didn’t let anyone near it, since KFOX was the only

communication anyone had, besides ham radio.

(Editor’s note: Going back into

history, the newspaper files of the Long Beach Press-Telegram show that

the city’s other radio station, KGER, at 435 Pine Avenue, was also on

the air during the emergency. Source: March 13, 1933 Press-Telegram

news story titled, “Radio Stations Aid In Locating Persons Missing In

Disaster.” KGER had been off the air for only 9 minutes, and little

damage was done to its studios at the Dobyn’s Shoe Store building.

Chief Engineer Jay Tapp told the paper that when the station came back

on, listeners were given a report on quake damage along Pine Ave. In

contrast, the story confirms Mr. McDowell’s memories of the event. The

wall of the KFOX building did indeed fall on the room where generators

and batteries were stored. The studio was so badly damaged,

broadcasting had to be done from the roof and then the alley.

Also, KFOX owner/manager Hal G. Nichols was hurt when bricks crashed

through the roof of his car, just as he was driving into the alley near

the building where the studio was located. His injuries were not

serious. By Sunday, March 12th, floors of the KFOX studio and

transmitting room were propped up with timbers to enable the staff to

carry on. Both KFOX and KGER it seems, did a great job keeping

telephone lines open with extra staff to establish contact between

friends and relatives and give news of those killed and injured in the

earthquake. Information was also given to the public regarding relief

stations for the injured, along with food and wood supplies. KFOX also

maintained radio communications with broadcast station KREG in Santa

Ana, where three people were killed in the earthquake. Both stations

shared information with each other regarding the disaster. While KGER

did a great public service, broadcasting history books seem to give

KFOX the credit for being “famous” for its coverage of the 1933 quake.

In one book, “Golden Throats and Silver Tongues-The Radio Announcers”,

it states that KFOX announcer Ted Bliss remained at the microphone for

52 hours before getting any sleep, after coverage of the disaster. In

both cases, many people at both stations helped in the efforts to tell

Southern California and beyond the news of the quake. And it is noted

here, that KGER radio also did its part in serving Long Beach well

throughout the disaster. The reader may be interested in the fact that

KGER was also known for its daily broadcasts of the Long Beach

Municipal Band, for many years. Some radio schedules from the late-‘20s

list both KFOX and KGER broadcasting the band at the same time! KGER,

1390-AM, reportedly went on the air December 12, 1926. The F.C.C.

history cards for KGER indicate the station was licensed January 7,

1927. After the original owner C. Merwin Dobyns died, KGER was

sold and aired religious programming for several decades. In June 1997,

the call letters of KGER were changed to KLTX, known as

“K-Light”. The station first aired mainly religious and

conservative talk shows, but it now airs a Spanish Christian format.)

(Reports about the emergency

broadcasts made by KFOX and KGER were also covered in the New York

Times, Los Angeles Times and Broadcasting magazine.)

L: So, we broadcast a lot of dispatches for fire and ambulances.

Somebody had a warning there was going to be a tidal wave, but I didn’t

announce it. I wanted to hear more than just some rumor. I guess

somebody announced it, because some people took off for Signal Hill. We

had one telephone line into the building and we opened an office down

in the garage. The telephone company building was a shambles, it was a

wreck, but they managed to hook us up with a line to city hall. I put a

test circuit on it and it was good. We had several hundred pairs going

into our station, so we had a lot of spare telephone lines. So, I sent

an amplifier down to broadcast from city hall, because that was where

all the action was. We had other news items that were broadcast from

the studio.

At the end of three days, things had quieted down pretty good. (Editor’s note: The March 13, 1933 story

in the Press-Telegram confirms this. It said, “When there was no news

of the quake to report, regular station programs of KFOX were

sandwiched in.”) I came on the air and I said, “Well, the

earthquake is pretty well under control. We’re now going to start

taking some commercial advertising for our station. Our office is a

shambles and we can’t use the phone. But our office staff and salesmen

are down in the garage. If anyone wants to buy advertising time, just

come around or we’ll send a salesman around to see you.” Pretty soon,

we were amazed to see a line of people waiting to buy advertising.

Major department stores, Goodyear, and others, all waiting in line to

buy time. We sold something like, oh I don’t know, $10,000 worth of

advertising in two days! So, we got back in business again.

Wrap Up-Some Final Questions

J: In the 1920s, DXing, or listening to distant radio stations

was a big fad. Did you get a lot of letters from distant listeners to

KFON and KFOX?

L: Well, in the early days, we only had 500-watts. But even when

we only had 100-watts (from March

1924 until November 1925), for some reason or another, we got

listeners and letters regularly from the tip of South America. Right

down on the Straits of Magellan, there was a little fishing village

down there. And they’d write to us, “We listen to you all the time. You

come in as good as any station in the United States. You don’t fade.” (Laughter) Well, I looked on the

map and said it must be a skip, maybe a couple of jumps, I don’t know.

And our signal landed on this little fishing village, nothing further

south. But we got a few other things too (letters and reception reports),

but that’s the one I remember, because it was so unusual. (Editor’s note: A radio station signal on

the AM band can skip out at night for hundreds or thousands of miles,

under the right conditions. In some years, those conditions were

enhanced by the sunspot cycle. The Long Beach Press reported that KFON

received letters of reception from Virginia and Oregon during its test

broadcasts in late-February of 1924. By 1927, the station was heard

often in Australia and New Zealand! This was partly due to fewer

stations crowding the Broadcast Band then; only a few hundred compared

to more than 4,500 AM stations in the U.S. today. Also, there was much

less man-made noise to interfere with AM reception, such as television

sets, computers, light dimmer switches, fluorescent lights, etc.)

J: Did you guys send out Ekko Stamps?

L: No, we never got into that at all.

(Editor’s note: Ekko Stamps

were special radio stamps collected by radio hobbyists in the 1920s and

‘30s. They were made by the Ekko Stamp Company of Chicago. They also

sold a scrapbook with the call letters of all the radio stations in

North America. Stations usually sent out the stamp with their call

letters on them for 5 or 10 cents, in return for a correct report of

reception of that station. The hobbyist would then place the stamp in

his scrapbook in the space designated for that radio station. Larry

McDowell apparently rarely answered the letters from distant listeners

to KFON and KFOX, or didn’t remember much about the Ekko stamps. I have

some copies of letters sent out by the station. Each one was signed by

station manager and owner, Hal G. Nichols. A KFOX QSL verification card

sent to a DX listener in Baltimore, Maryland in the 1930s signed by

Nichols did indeed have an Ekko stamp on the card. The radio hobby

magazine RADEX in the ‘30s also listed KFOX as a station which sent out

Ekko stamps. Finally, I found a letter from 1944 sent to a person in

Berkeley, CA who heard the KFOX signal. This letter was signed by L.W.

McDowell, but there was no Ekko Stamp on it).

J: What about Clarence Crary and Frank Goss?

L: Yeah, Clarence Crary was a singer, piano player and a

salesman. He even worked for us when we were in the Jergins Trust

Building. He played the piano and took phone calls for numbers people

wanted him to play. And between times, he’d go out and sell for us.

(Editor’s Note: In the August 4, 1928 issue of Radio Doings magazine,

Clarence Crary’s picture is shown with the KFON program schedule. He’s

listed as an announcer. He also did a Friday night program at 9 p.m.,

called “Ye Olde Song Album”, described as an hour of old-time music. He

also did a show with a woman on KFON titled “Doris and Clarence”.

L: Frank Goss was the city editor for the Long Beach

Press-Telegram.

(Editor’s note: The paper in

1924 listed Goss as Sunday editor. He later became the paper’s radio

column editor and writer. Frank P. Goss worked for the Long Beach

Press-Telegram from 1923 until his retirement in 1952. Mr. Goss

was named City Editor of the Press-Telegram in 1928. His 1973

obituary says that Goss was the voice of KFON/KFOX news from 1924 until

1942, and that the newscasts were sponsored by the Press-Telegram for

those 18 years.)

When we first started putting news on at 4:00 p.m., Goss would pick up

all the stuff off the press (news

wire services) and get in his car and come down to the station

at the Markwell Building, and come up in the control room and broadcast

the news for 15 minutes. Later on, when I found out about how to hook

up a remote telephone line, we let him stay in his office to do it.

(Editor’s note: Frank P. Goss

must’ve enjoyed radio broadcasting. In a June 28, 1925 schedule of

KFON, he is listed as the station’s Program Arranger and Studio

Director. The Press-Telegram radiocast of news and sports was initially

on the air on from 5:30-6:00 p.m., Monday through Saturday. By 1928,

Frank Goss did the morning news at 11:30 a.m. and an afternoon newscast

was on at 4:00 p.m. His radio work at KFON/KFOX must have been

part-time, while he continued his employment at the newspaper.)

L: Goss was our news announcer for a long time. He liked to do it

and being the city editor helped too. Later on, we had our own teletype

in the station. Most stations relied on newspapers at first. As long as

we dealt with the newspaper, we were all right (legally). Later on, we

subscribed to United Press and Associated Press. But before that, we

dealt with our local paper, so it was fine to get news that way. To us

though, we couldn’t sell the news in those early years. You couldn’t

give it away! Now, there’s news every 15 minutes. We never did sell the

news.

(Editor’s note: Frank P. Goss

(1879-1973), who was City Editor of the Long Beach Press-Telegram and

was the KFOX Press-Telegram newscaster from 1924 until 1942, was not

the same person as Frank Goss (1911-1962) who was an award-winning

newscaster for 22 years at KNX and the CBS Radio Pacific Network).

I stayed with KFOX 30 years. Hal died, Earl died. I was the last one

left. Warinner died. (Editor’s note:

W.H. Warinner was Hal Nichol’s partner and formed Nichols and Warinner,

Inc., the owners and licensee of radio station KFON and KFOX for many

years.) And, Mrs. Nichols, she didn’t want the station anymore.

So, they were going to sell it to someone, so I sold my share of it.

J: Who was Warinner?

L: He was the guy with the money. He came out from Denver and knew Hal

there. He had an automobile agency and had all the money and financed

the station.

END OF INTERVIEW

Post

Interview

In addition to his duties as chief engineer, Larry McDowell was later

vice-president of KFOX radio. In the late-‘30s and 1940s, he was also

the station’s advertising and sales manager. In the 1950 United States

Census, McDowell listed his occupation as radio station Manager.

He left KFOX in 1954. He went on to become director of the Long Beach

Marine Department until his retirement.

As of 2022, the license for KFON/KFOX (KFRN 1280 today) is

98-years-old. We stated earlier in this interview that KFON

changed call letters at midnight on December 30, 1928 and became KFOX.

The station was on several frequencies from 1924 until November 11,

1928. That’s when the Federal Radio Commission assigned the station to

1250 kilocycles. On March 29, 1941, the FCC shifted KFOX to 1280

kilocycles. In the late-1940s, KFOX owners applied to the FCC to raise

the station’s transmitting power to 5,000 watts. However, this request

was denied. Later, when television forced radio stations to change the

way they entertained Americans, KFOX settled on a format of playing

Country music from 1959 until 1977. The 1,000-watt station on 1280-AM

from Long Beach was sold again and this time it was the end of an era.

The historic KFOX call letters, which had served Long Beach for nearly

50 years were dropped. The station was purchased by the Christian

broadcasting group, Family Radio Network. On November 23, 1977, the

KFOX call letters were changed to KFRN (the initials of the licensee

and owner of the radio station). KFRN, 1280-AM, continues to

broadcast from Long Beach as a 1,000-watt non-commercial radio station

with a religious format.

Jim Hilliker

Monterey, California

September 1998

(Edited again December 2022)

|