|

SUPERPOWER

REDEFINED

The term “superpower” was

bandied about frequently in the early years of American radio broadcasting, but

its exact definition was continually evolving.

In 1923, superpower referred to the

newly-authorized 1,000 watt “Class B”.

Listeners feared that their powerful signals

would wipe out other stations on the dial, which typically operated at from 50

to 500 watts.

In 1925, five “Class B” stations were raised

to an unheard-of 1,500 watts, but with the proviso that they would have to

reduce power if they caused interference.

The following June, two stations – WLW and

WSAI in Cincinnati – were granted increases to 5,000 watts.

One of the prime developers of

radio science at the time was the American industrial giant General Electric.

In 1922, the company had opened its own

station, WGY in Schenectady, New York, one of the foremost broadcasters in the

country.

From its 54 acre radio test site In South

Schenectady, G.E. undertook a program of research and development for higher

power transmitter technology.

It was from that site on January 30, 1926,

that WGY conducted the first ever test at 50,000 watts.

Nearby listeners were afraid to turn on their

sets for fear that the powerful signals would blow out their tubes or

loudspeakers.

“Radio Digest” magazine reported,

“It was

apparent that the observers had expected to be literally knocked from their

chairs by the high power, and were somewhat disappointed that something of that

sort did not occur.”

But hundreds of other listeners cooperated in

the test program by sending in more than 1,500 signal reports.

Accounts of good reception came in from as far

away as the West Coast.

The consensus of the test was that WGY’s

signal strength was nearly doubled while fading and static interference was

reduced; yet the tuning of the station was still sharp, causing no more

interference to adjacent channels.

Shortly thereafter, WGY became the first

American station to commence regular broadcasting at 50,000 watts.

In just six short years, the definition of

“superpower” had jumped from 1,000 watts to 50,000 watts, and by 1931, 23

stations operating on clear channel frequencies had been authorized at that

power level.

But the desire for still more transmitter

power didn’t end there.

THE

NEVER-ENDING QUEST FOR MORE POWER

In

August of 1927, the Federal Radio Commission permitted WGY to test a 100,000

watt transmitter during a thirty day period between the hours of midnight and

1:00 AM using the call sign W2XAG.

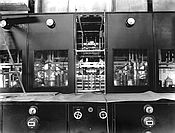

It

employed a new 100 kW GE water-cooled tube, using just two tubes in the RF

amplifier and three in the modulator.

The test results demonstrated a marked

increase in signal strength within a range of 500 to 600 miles - mostly east of

the Mississippi and north of North Carolina.

A

listener in Virginia noted that WGY nicely overrode the noise from a nearby

electrical storm. Another,

in Minnesota, reported that WGY’s volume exceeded that of his local station.

Next, in March, 1930, WGY conducted another

series of tests at 200 kW, transmitting from 4:00 to 6:30 AM over a seven day

period.

This time, a flood of reception telegrams arrived

from the Pacific Northwest, Alaska and Hawaii.

Not

willing to be outdone, the engineers over at Westinghouse in Pittsburgh had

developed their own high-powered tube, rated at 200 kW, and the company

conducted test transmissions from its own station, KDKA, at a reported 400 kW.

These 1931 tests were aired between 1:00 and

6:00 AM from KDKA’s 130 acre site in West Saxonburg using the call sign W2XAR.

Meanwhile,

at WLW in Cincinnati, talks were taking place about even higher power.

Radio manufacturing entrepreneur Powel

Crosley, Jr., had progressively increased the power of his station in steps of

10x– from 50 watts to 500 watts in 1923; to 5,000 watts in 1925, and then to

50,000 watts in 1928.

He was well aware that a 10x increase in power

only produced a 3x increase in signal strength and coverage, and so felt that

anything less than a 10x increase didn’t justify the investment.

And as one of the country’s major

manufacturers of radio receivers, he also recognized that most new radios now

incorporated an AGC (Automatic Gain Control) circuit, which eliminated any

increase in volume the higher power levels would cause.

And so the natural next step for Crosley would

be to step up to 500,000 watts – a power level never before attempted.

His engineers calculated that such power would

give WLW a noise-free signal out to a radius of 250 miles.

Crosley

had lots of friends in high places, and somehow he was able to coax the FCC to

give him experimental authority at 500 kW.

It authorized WLW for 50,000 watts of

“licensed” power plus another 450,000 watts of “experimental” power under the

call sign W8XO.

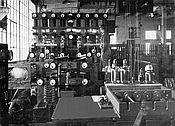

Discussions

began in May of 1932 regarding the construction of the huge transmitter that

would be needed.

RCA would be the primary contractor, and G.E.

and Westinghouse would each build significant parts of the system.

By the end of 1932, a final design had been

approved and construction on the monstrous new transmitter began the following

year.

It utilized WLW’s existing 50,000 watt Western

Electric transmitter as an “exciter” to drive three power amplifiers of 165 kW

each.

Their outputs were combined in series to feed the new

831-foot diamond-shaped Blaw-Knox tower that was being erected to launch the big

signal.

There were two modulating amplifiers employing Class

“B” high level modulation to create the audio part of the signal.

Between the RF amplifiers and modulators, this

immense system needed twenty of the new 100 kW G.E. water-cooled tubes

On

May 2, 1934, President Franklin Roosevelt pressed a gold key in Washington that

turned on WLW’s transmitter for the first time.

Although initially operated only after

midnight, the experimental authority was soon expanded to encompass the entire

day.

Field measurements showed, as predicted, that WLW had

tripled the size of its coverage area.

OTHERS CLAMOR TO

JOIN THE CLUB

No

sooner does one kid on the block get a new toy before everyone else wants one

too.

Such was the case with superpower AM broadcasting.

Other broadcasters noted that WLW was enjoying

great success and attracting large audiences and prime advertisers with its new

signal.

It

was

effectively operating as a “one-station network” by covering a third of the

country with a quality nighttime signal.

Several of the country’s major broadcasters

also wanted in on the action, while still others were afraid they could lose

their clear channel status if they didn’t also seek a power increase. (Clear

channel stations enjoyed the exclusive use of their assigned channels

nationwide.) In

1935, WGN in Chicago, WSM Nashville, and both KFI and KNX in Los Angeles had

filed for either 250 kW or 500 kW.

NBC was drawing up plans for a new 500 kW

plant for its flagship station, WJZ in New York City.

By 1936, a total of fourteen clear channel

stations had applied for superpower.

This was now creating a problem at the FCC –

WLW was operating under a unique experimental authority that needed to be

renewed every six months, but for additional clear channel stations to increase

their powers, a change in regulations would be required

While

they considered this dilemma, a battle between the “haves” and the “have nots”

was brewing on the sidelines.

A number of smaller regional broadcasters that

did not enjoy the advantage of wide area coverage began to pressure the FCC to

break down the clear channels and permit one or two additional stations to use

the same frequency on opposite ends of the country.

Of the original forty clear channel

frequencies that had first been authorized in 1928, only thirty were still

operating as full time exclusive clear channels.

The other ten channels were now being shared

by two stations, using either time-sharing, frequency synchronization,

directional antennas, or the shared use of a single transmitter (in the case of

WLS and WENR in Chicago).

Combining these two conflicting issues into

one case, the FCC established a “Superpower Committee” consisting of

Commissioners Craven, Payne and Case.

They were assigned the task of reviewing the

entire FCC regulation policy for clear channel stations.

As

they first envisioned the case, a realignment of the broadcast band was be

needed, with fewer clear channels but allowing for superpower on some of the

remaining ones.

But the situation would soon prove much more

complicated.

For

the purpose of influencing the commissioners in favor of their cause, thirteen

of the biggest clear channel broadcasters formed a lobbying organization called

the Clear Channel Broadcasting Service (CCBS).

A staff of lawyers and engineers was assembled

in Washington for the purpose of influencing the Commission.

But even as these stations were joining forces

to lobby the FCC, other broadcast interests were simultaneously aligning to

block the adoption of superpower under the banner of an organization, called the

“National Association of Regional Broadcast Stations” (NARBS).

This second group was principally composed of

lower power local and regional stations around the country that did not enjoy

the benefits of a clear channel assignment -- and even if they did, they lacked

access to the ample funds necessary to construct such a superpower station.

(WLW estimated its 500 kW construction cost at

$500,000 - or $9.5 million today - with its electric power and transmitter

operating cost being another $66,000 a year, or $1.2 million today).

These smaller broadcasters feared losing their

audiences and lucrative network affiliations to an exclusive monopoly of

superpower clear channel stations.

In

June of 1936, the Texas Association of Broadcasters was organized, and its first

act was to direct a resolution to the FCC opposing the adoption of superpower.

The battle lines were now being drawn, and

full-scale open class warfare between the broadcasters was about to begin.

THE

FCC HOLDS HEARINGS

The

FCC’s Superpower Committee held three series of hearings in May, September and

October of 1936.

Dozens of the most powerful and influential

broadcaster executives set aside their business and personal plans so they could

travel to Washington to testify.

The

CCBS group of thirteen clear channel stations first presented its case, and

declared that there should be NO statutory maximum power limit for AM

broadcasting.

It argued that clear channel stations provided

an essential service to rural listeners, and that the economics of the existing

broadcast structure would otherwise result in too many stations serving the

large cities while too few attended to the sparsely-populated rural areas.

The

CCBS projected that a single five million watt transmitter would cover the

entire country. Powel

Crosley, Jr., also testified in favor of superpower and improved service to

rural America.

He declared that his WLW

“endeavored to

cover the ‘no-man’s land’ between existing station service areas, to deliver,

winter or summer, in spite of atmospheric or other forms of interference,

satisfactory reception for the radio listener who cannot afford the more

elaborate and costly receiving sets.”

He noted that WLW’s daily mail had quadrupled

after the power increase, and that the bulk of its new fan mail came from small

towns and rural districts.

For

its part, the NARBS, representing 81 member stations in 34 states, testified in

opposition to superpower.

It projected financial ruin for regional

stations, and claimed there was no justification for superpower, either

technically, economically or socially.

It predicted that the high power stations

would cause international interference, and suggested that, if approved, such

stations should be located in localities where they would render unique services

that could not be duplicated by any other means.

CBS

Chairman William S. Paley testified in opposition, observing that superpower

would make

“the big fellow stronger and the little fellow

weaker.”

He also pointed to the forthcoming

introduction of television and expressed concern about the cost of building high

power AM and television facilities at the same time.

Nonetheless, although he was generally opposed

to the concept, he declared that, if it were approved, CBS would apply for its

full quota of superpower outlets.

Former

Federal Radio Commissioner Harold LaFount laid out a strong argument against

superpower.

He declared that “Half

of the non-network stations in the country are not showing a profit.

All the major stations are affiliated with the

networks, providing duplication of programming which is now adequately provided

by the chains of existing stations.

If the networks affiliate with superpower

stations, they would be likely to drop their regional affiliates, leaving these

stations to provide for themselves.”

LaFount also observed that there were

“374 full time stations having an aggregate nighttime power of 2,188,650 watts.

Of these, 2,000,000 watts were allocated to

network affiliate stations on clear channels.

…. 97% of the total power is used by 165 full

time network affiliated stations, leaving just 58,350 watts for the 209

independent full time stations.”

Dr.

Greenleaf Pickard, a respected Boston radio engineer, expressed his concern

about international interference, especially in the Western Hemisphere.

He also pointed out that stations could

increase coverage without raising power by adopting more efficient antenna

designs, such as the full wave Franklin antenna.

Faced

with this unexpected opposition to superpower, the FCC commissioners chose to

punt – they delayed their decision and declared that more studies and tests were

needed.

WLW’s

SUPERPOWER AUTHORIZATION IS RESCINDED

For

over three years, WLW had enjoyed its nationwide superpower exclusivity,

operating under temporary experimental authorizations that needed to be renewed

every six months.

On December 1, 1937, it submitted another one

of these routine applications.

But to their shock, instead of receiving

another rubber stamp approval, the application was designated for hearing by

Commissioner George H. Payne, a member of the Superpower Committee.

Hearings

on the WLW renewal began at the FCC in July of 1938.

Powel Crosley marshalled a team of lawyers and

engineers to make his case before the commissioners.

It was a contentious, hard fought battle, but

in the end the three-commissioner panel voted unanimously to not renew.

Crosley appealed the decision to the courts,

but his appeal was also denied.

WLW’s

24-hour superpower authority terminated in 1938, and the station returned to 50

kW on March 1, 1939, although it retained its original experimental authority to

broadcast after midnight as W8XO.

Despite this setback, the huge transmitter did

not go silent forever.

It’s rumored that the big rig, which could be

easily heard in Europe, was pressed into service on several occasions during

World War II to broadcast clandestine messages to agents behind enemy lines.

After

the defeat of his superpower case, Powel Crosley seemed to have lost interest in

radio broadcasting, and he turned his personal attention to developing other

consumer products, including automobiles and refrigerators.

But he continued to own WLW until he died in

1961.

Crosley Broadcasting was sold to AVCO Electronics in

1975.

BROADCASTERS

TAKE AIM AT CONGRESS

By

1937, frustrated by the FCC’s intransigence, the clear channel broadcasters

began airing announcements encouraging their listeners to write their

congressmen to support high-powered broadcasting.

Not to be outdone, the regional broadcasters

also began lobbying their local congressmen, most of whom highly valued the

support of their local radio stations to publicize their Washington activities

and re-election campaigns.

Accordingly, the battleground moved from the

FCC to Congress.

At this same time, the Senate was debating its

approval of the “Havana Treaty” – also known as the “North American Regional

Broadcasting Agreement” or NARBA.

This was a 1937 agreement between the United

States, Canada, Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Haiti to realign the AM

broadcast band and reapportion its channels among the countries.

However, the agreement could not take effect

until ratified by the Senate, and Montana Senator Burton K. Wheeler announced he

would oppose the treaty unless the Senate also passed his Senate Resolution 294,

now known as the “Wheeler Resolution”, establishing a maximum AM broadcast power

of 50,000 watts. On

June 13, 1938, the Senate adopted its “Sense of the Senate” resolution stating

that the FCC should not allow any stations to operate at powers greater than

50,000 watts.

Superpower, it declared,

“would tend to

concentrate political, social and economic power and influence in the hands of a

very small group … and … would have adverse and injurious economic effects on

other stations operating with less power.”

Taking

its cue from the Senate, the FCC implemented a 50,000 watt cap on all AM

broadcasting the following year.

It seemed that the issue was now finally

settled, but in fact the battle for superpower was far from over ….

THE

CLEAR CHANNEL DEBATE GOES ON … AND ON … AND ON …

Although

the FCC had now declared an upper power limit, it was still uncertain about how

to organize and manage the clear channel frequencies.

Should clear channel stations continue to

enjoy their nationwide exclusive use of their frequencies, or should the

channels be broken down to allow additional stations to occupy them in disparate

parts of the country?

Hearings and studies on the topic began in

1939 and, except for a temporary hiatus during World War II, dragged on

continuously until 1948.

The focus was now on opening up opportunities

for other stations to use the channels, creating more regional stations instead

of covering vast areas with high power signals.

But the clear channel stations, as represented

by the CCBS, had not thrown in the towel on superpower, and in 1948 they

submitted a plan calling for twenty stations to operate at 750 kW.

Even though the FCC was now unlikely to adopt

such a plan, their strategy appeared to be to keep the superpower issue in play.

As long as there was the possibility of

high-powered authorizations, the channels would not be broken up.

This debate was further complicated by the

expiration of the NARBA treaty in 1949.

The renewal negotiations that followed were

contentious – Cuba, Mexico and other countries wanted to establish their own

operations on the U.S. clear channels.

These negotiations dragged on for years,

effectively stalling any further progress on the clear channel issue.

Congress did not finally approve the new NARBA

treaty until 1960.

Ultimately,

in 1961, the FCC’s Docket 6740 finalized the breakup of the clear channels and

codified in its regulations a definite 50 kW power limit.

Gradually, new “Class I-B” or “Class II”

stations were assigned to the clear channel frequencies, sharing the channels

with the legacy “Class I-A” stations.

The CCBS appealed the ruling to Congress, and

continued to press for its 750 kW assignments, but their further lobbying

efforts now fell on deaf ears.

The organization finally closed its Washington

office in 1968.

ASPIDISTRA

There

is one fascinating post script to the superpower story, and it involves the

British black propaganda station “Aspidistra”.

In 1938, RCA was so convinced the FCC would

authorize 500 kW for its New York City flagship station that it decided to get a

head start on the project and begin construction.

It began the assembly of a second 500 kW

transmitter, based on the WLW design but incorporating numerous improvements.

Similar to WLW, it incorporated a 50 kW

“exciter” followed by high level Class “B” amplifier and modulator stages

employing 26 high power tubes.

But then, when Congress intervened to stop the

FCC proceedings, RCA found itself with a white elephant on its hands.

When

World War II began in Europe there were suddenly new urgent requirements for

high-powered transmitters.

In 1942, the British Secret Service purchased

the WJZ transmitter for £165,000.

RCA’s engineers modified it to produce 600 kW

of power and to allow for quick frequency changes, and the entire system,

including antenna towers, was shipped to Britain.

A ship carrying the 50 kW exciter and one of

the three towers was sunk by a German U-Boat, and so replacements then had to be

sent.

Finally, the completed transmitter was installed in

an underground bunker at Crowborough in Southeast England, and the station

code-named “Aspidistra” went on the air November 8, 1942.

Aspidistra’s

sole purpose was to transmit fake programs to confuse the enemy.

It laid down such a powerful signal over

Germany that it was easily believed to be a local station.

When Allied bombing raids took place over

German Cities, the Reich’s local stations would be turned off so that the enemy

planes couldn’t “home in” on their signals.

But at the exact moment the German stations

left the air, Aspidistra would begin its transmissions on the same frequency,

impersonating the local stations with German announcers and giving false and

demoralizing information to the German audiences.

For example, it announced that counterfeit

currency was being circulated, and that evacuation orders were given for areas

not being bombed.

The frustrated German authorities responded by

announcing

"The enemy is broadcasting counterfeit instructions

on our frequencies. Do not be misled by them.

Here is an official announcement of the Reich

authority."

But then Aspidistra would broadcasts the same

message, further confusing German listeners.

After

the war ended, the Aspidistra site became a conventional BBC medium wave

station.

The original WJZ transmitter continued in use

until it was finally retired by the BBC in 1962.

TODAY,

50 KW IS JUST FLEA POWER

Even

today, 50,000 watts remains the ceiling power level for AM broadcasting in the

United States.

However, superpower AM broadcasting has

existed for decades in many parts of the world.

There are numerous such stations in our own

hemisphere, including Trans World Radio in Bonaire (440 kW), and XEW in Mexico

City and Radio Globo in São Paulo, Brazil (250 kW each).

But

even those power levels pale by comparison to what exists in other parts of the

world.

There are now more than thirty medium wave

broadcasters around the world operating with at least a million watts.

In Hungary, Antenna Hungária operates on 540

kHz with 2 million watts with an all-solid-state system built by the Canadian

manufacturer Nautel, Ltd.

Saudi Arabia is said to operate three stations

at two megawatts each, and Viet Nam has one such station.

For many decades, the Voice of America has

operated superpower medium wave transmitters in different parts of the world.

In the 1970’s, the VOA transmitted into China

from Okinawa with one million watts on 1174 kHz, and it still operates at this

power level today on 1575 kHz from Thailand and on 1170 kHz in the Philippines.

As

the AM band declines in popularity and importance around the world, a number of

high powered stations have been shut down due to their high operating costs.

European government stations have especially

become victims to these budget cuts.

However,

there are numerous Christian stations that continue to blast out powerful

signals, such as Trans World Radio in Monte Carlo.

The mammoth installations of these superpower

stations undoubtedly represent the pinnacle of high-power radio engineering.

When the last one disappears, the world may

never see their kind again.

This article

originally appeared in the July, 2019 issue of the"Spectrum Monitor" Magazine.

REFERENCES:

“Broadcasting” Magazine

·

10-15-31

“Nine Stations Given Maximum Power”

·

9-15-35, “Clear Channel Stations Study

Superpower”

·

5-1-36, “NBC Outlines Plans for WJZ 500 kW”

·

5-15-36 “Joint Hearings on Superpower”

·

6-15-36 “Super Power Held Basis of Monopoly”;

“FCC Sets Hearings on 500 kW Pleas”

·

7-1-36, “Four Stations File for 500 kW Power”

·

10-15-36, “Case for Clear Channels and

Superpower”

·

4-15-38, “Reallocation Held Up by Treaty Delay”

·

6-15-38, “Superpower Eliminated as Issue”

·

8-1-38, “Value of 500 kW Tests Related by WLW”

·

11-1-38, “Final WLW Ruling Unlikely This Year”

·

1-1-39, “FCC Superpower Report Still Delayed”

·

3-1-39, “Stay Refused, WLW Returns to 50 kW”

·

1-19-48, “Clear Channel Battle Resumes”

·

5-24-48, “Johnson Seeks FCC Delay”

·

4-11-49, “Power Ceiling House Bill Introduced”

“Radio Digest” Magazine:

·

January 1925, “Five Super Power Licenses Granted”

·

May, 1925, “Class B Stations Ask Higher Power”

·

9/12/1925:

“High Power Downs Static”

·

Jan. 30, 1926, “WGY to Send Special Test Jan. 30”

“Radio News” Magazine:

·

October, 1927, “New Experimental 100 kW

Transmitter at Schenectady”

·

April, 1931, “The Giant Tube KDKA is Using at its

400 kilowatt Station”

“Billboard” Magazine, Dec 13, 1948, “Election’s

Effect on Radio”

Encyclopedia

of Radio 3-Volume Set - edited by Christopher H. Sterling

“Hearings before Interstate and Foreign

Commerce Committees”, 1948

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d03588525g;view=1up;seq=9

“Daytime Radio Broadcasting – Hearings before

85th Congress”, 1957, Google Books

“Allied 'Radio Aspidistra' Of WW 2, A Drama

Documentary Radio Broadcast”, by

The

Radio TV & Audio Collection.

https://archive.org/details/AlliedRadioAspidistraOfWW2.ADramaDocumentaryRadioBroadcast

“The Biggest Aspidistra in the World”

https://web.archive.org/web/20070927012954/http://www.qsl.net/g0crw/Special%20Events/Aspidistra2.htm

“Schneier on Security:

Aspidistra”:

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2008/11/aspidistra.html

“Radio World” Magazine, 9-5-2018 - “Who’s Got

the Biggest, Meanest AM Flamethrower?” by James O’Neal:

https://www.radioworld.com/news-and-business/whos-got-the-biggest-meanest-am-flamethrower

Wikipedia:

“List of European Medium Wave Transmitters”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_European_medium_wave_transmitters

“Wavescan” by Dr. Adrian Peterson

·

“American Mediumwave Radio on High Power”:

http://www.ontheshortwaves.com/Wavescan/wavescan140907.html

·

“Medium Wave Broadcasting on High Power”:

http://www.ontheshortwaves.com/Wavescan/wavescan140907.html

“2 Megawatt Transmitter for Antenna Hungária”:

https://www.nautel.com/2-megawatt-mw-transmitter-antenna-hungaria/

The author wishes to

recognize David Gleason and his comprehensive web site

www.americanradiohistory.com.

These historical articles would not be possible without the tremendous

research facility that David provides.

|