|

www.theradiohistorian.org

Copyright

2023 - John F. Schneider

& Associates, LLC

[Return

to Home Page]

(Click

on photos to enlarge)

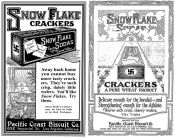

Advertisements by the Pacific Coast Biscuit Company. The

company's trademark, a swastika, quickly went out of favor in the late

1930's.

Chet Huntley - 1930 and 1968.

Here is Chet Huntley at KPCB in 1934, producing a low-budget opera

program. Phonograph records provided the music plus the sound

effects of a live performance. ("Puget Sounds" by Dave Richardson)

Saul

Haas was the president and major stockholder of KIRO from 1934 to

1963. He was primarily responsible for the station's rise from a

small station to a Northwest powerhouse.

KIRO's completed 50 kW transmitter - Western Electric model

401-A. It was the factory protytpe, serial number 1.

After Pearl Harbor, the KIRO transmitter was declared a strategic site

and was guarded by National Guardsmen 24-hours daily. James

Hatfield is on the telephone.

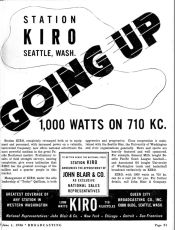

A trade magazine advertisement promoting KIRO's increase to 50,000

watts,1941.

The KIRO towers on Maury Island -

a recent photo by Jerry Burling.

|

|

From Soda Crackers to Radio

The Pacific Coast Biscuit

Company was a part of the Centennial Mills

(Krusteaz Brand), which operated a flouring mill on East Marginal Way

in

Seattle in addition to several other locations around the country. Moritz Thomsen (1850-1932) was the

multi-millionaire

president of Centennial Mills. In 1927,

after competitor Fisher Flouring Mills put KOMO on the air in Seattle,

Thomsen

felt the need to match his competitor’s radio activities. On April 1, 1927, he debuted KPCB, just

four months after KOMO began broadcasting.

The KPCB call letters were an acronym for “Pacific Coast

Biscuit”.

KPCB

broadcast from a tiny studio in the Central Building, with its 50-watt

Western Electric transmitter atop the Pacific Biscuit mill at 4111 East

Marginal

Way. The first frequency was 521 meters

(575 kHz). The inaugural program

included an address by Seattle Mayor Bertha K. Landes, and then music

by a

string quartet and an eight-piece concert orchestra. KPCB

called itself the “Snowflake Station”, promoting the company’s Snowflake soda crackers.

In June of

that year, the newly-formed Federal Radio Commission moved

KPCB to 1300 kHz and required it to share that frequency on a

50/50-time basis

with KGCL, another Seattle station that was owned by radio pioneers

Louis

Wasmer and Archie Taft. Both stations

were relocated to 1210 kHz in 1928, and KPCB increased power to 100

watts at

that time. For its part of the

time-sharing schedule, KPCB was on the air Mondays, Wednesdays and

Friday until

4:00 PM, at which time KGCL took over the frequency.

On Tuesdays, Thursday and Saturdays, this

arrangement was reversed. The two

stations also divided time equally on Sundays.

This

division of time meant that neither station could attract a

sizeable audience or much advertising revenue. Although KPCB was owned

by a well-financed corporation, Pacific Biscuit never invested the kind of money

that Fisher

put into KOMO, and it was always the butt of local jokes for its lack

of funds

to buy equipment or replacement parts. As

one example, when it needed to make a remote

broadcast, the station’s only

microphone would be rushed to the remote location by taxi while

phonograph

records were played to cover the air time.

Its programs were second-rate, often originating from

transcription

recordings.

In 1929,

Wasmer and Taft reorganized KGCL under the corporate name

Wescoast Broadcasting Company and acquired an interest in KPCB. Their plan was to create a regional network

of Washington stations, with KPCB covering the Seattle area. KGCL was moved to Wenatchee and the call sign

changed to KPQ. In Wenatchee, KPQ

operated with 50 watts full time on 1500 kHz, while KPCB moved down the

band to

650 kHz where it was put on a limited daylight schedule to protect WSM

in

Nashville. This meant the station stayed

on the air until 7:30 PM in the summer months, but went off at 4:15 PM

in

December.

In 1929, KPCB

moved its transmitter to the new ten-story United Shopping

Tower at 217 Pine Street. A pair of

125-foot towers was erected on the roof, with a six-wire cage antenna

suspended

between them.

The

agreement with Wasmer and Taft apparently was short-lived, because

KPCB was reorganized in November, 1930, under the name Queen City

Broadcasting

Corporation with 2,500 shares of stock primarily in the hands of the

Thomsen

family. Moritz Thomsen, the family

patriarch, died in 1932 at the age of 82, and family members likely

continued

to manage the flour mill and radio station.

In 1934, at the depths of the

Depression, KPCB hired a young University

of Washington graduate named Chet Huntley for just $15 a week in cash

plus free

rent and meals, which were obtained in exchange for advertising trades

with an

apartment building and a restaurant. In

addition to announcing programs, Huntley would buy a newspaper on his

way to work

and rewrite stories for the station’s news broadcasts.

In 1935, Huntley’s request of a raise from

$15 to $25 a week was declined – he was told the station really

couldn’t afford

the $15. (Yes, this was the same Chet

Huntley who later became an NBC network news co-anchor.)

Also in

1934, KPCB became a part of a program-sharing arrangement with

KMO, KXRO, KVOS and KXL, called the Pacific Northwest Network,

Saul Haas

Saul Haas

(1896-1972) was born in New York City, the son of Romanian

Jewish immigrants. His experiences as an

immigrant and laborer inculcated in him a pro-labor, liberal slant from

an

early age. In 1918, he came west and

joined

the Portland News as a reporter. After

that, he tried his hand at running a newspaper in Port Angeles before

returning

to New York to work for the Hearst International News Service. In 1921 he joined the staff of the Union

Record, owned by the Seattle Labor Council, buying out the paper in

1925 and continuing as its managing editor

and a

minority stockholder until it folded in 1928.

As a

political liberal with a keen interest in politics, Haas made many

influential

connections with like-minded people during his days at the Union Record. One of his closest friends was State Senator

Homer

T. Bone, a farm and labor advocate from Tacoma.

They formed an inseparable friendship that lasted a

lifetime. In 1932, he managed Bone’s

campaign for the

U.S. Senate, and saw him swept into office on the coattails of Franklin

Roosevelt’s landslide win. This briefly

took him to Washington, D.C., where he served as Bone’s administrative

assistant. Haas’ loyalty was then rewarded

with his appointment as the Collector of Customs for the Seattle Port

District. He continued to grow in

importance as a figure in the Washington Democratic Party, and was the

state

manager for FDR’s second campaign in 1936.

Haas’

involvement in radio began in 1931, when he was appointed as the

receiver for KJR’s second bankruptcy. He

took a keen interest in the power of radio to influence people. Not long after this, Moritz Thomsen’s son

Charles

had a legal run-in with Saul Haas, the director of the U.S. Customs

Office in

Seattle . As a settlement for the

skirmish, Haas was able to acquire 700 shares of KPCB stock, valued at

$20,000.

Finally, his

involvement in the station’s operation led him to arrange a purchase of all the remaining shares in the KPCB corporation, Queen City Broadcasting

Company, from

the Charles M. Thomsen Holding Company for

$12,000. On October 15, 1935, Haas

became 67% owner and vice president of KPCB. A

group of ten other businessmen held the remaining shares: Louis K. Lear, president of Green Lake State

Bank and another Haas friend, helped bankroll the station and became

its

president. John Hagen was a co-vice president.

George B. Storer, a well-known East Coast broadcaster,

held 10% of the

stock. Harold J. “Tubby” Quilliam was

hired away from KJR/KOMO to be the new general manager.

A recent Washington State College graduate, James

B. Hatfield, became the new engineer.

Changes took

place quickly once Haas was in control - he had the drive

and determination to make it a first-class station.

The studios were moved into larger quarters

in the basement of the Cobb Building, a space recently vacated by KOMO.

On October 15, 1935, Vice President

Garner and

other dignitaries attended a ceremony boosting the station’s power

from 250

to 500 watts. The same day, KPCB’s

call

letters were changed to KIRO, which Haas thought had a pleasing sound. In the following months the staff size nearly

doubled as talented people were hired away from other stations. Better programs were created, a professional

sales organization was hired, and before long KIRO was operating in the

black.

KIRO

programs were a mixture of network, local and transcription

programs. It called itself “The Friendly

Station”, adopting an informal announcing style that differentiated it

from the

formal, stuffy style of most other stations. A

station mascot character named “KIRO Looie”,

an Arabian sultan, was created for use over the air and in printed ads. An announcer in the Looie character’s voice

hosted a daily early-morning request program called “KIRO Looie’s Time

Klok Klub”. Max Dolin, the

Cuban-born former NBC network

West Coast music director, broadcast a live 30-minute live orchestra

program

every Sunday night, sponsored by Gold Shield Coffee.

A separate “home service auditorium” was

inaugurated in 1938. Seating 250 people

and featuring a model kitchen and electric organ, it was the source of

daily

cooking schools for housewives and a Saturday children’s cooking

program. In 1939, “Father Goose Comes to

Town”, written

by Dorothy Mason. presented dramatized nursery tales. Singing

station break jingles were another

innovation, with “Columbia’s Voice in Seattle” being sung to the tune

of

“Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean”. Also

that year, a 25-year-old pianist named Freeman Clark began

playing

twice weekly on KIRO. He would later team

up with Eddie Clifford, and the Clifford and Clark piano duo would be a

Seattle

radio staple for many decades.

In 1937,

CBS’s purchase of KNX in Hollywood caused domino-effect changes

of station affiliations up and down the coast. As

a part of this shakeup, Haas began

negotiations with CBS, ultimately resulting in the network moving it’s

Seattle

affiliation from KOL to KIRO. In

1938, KOL filed a lawsuit against Haas and Bone over the network

“theft”, but

it was dismissed by the courts. KIRO would carry CBS's dramas,

comedies,

news, sports, soap operas,

game shows

and big band

broadcasts during the "Golden Age of Radio"

and beyond.

The Battle for 710 kHz

Saul Haas’

close personal relationship with Senator Homer Bone gave him

a powerful friend in Washington. (While

it’s

possible that Bone may have had a business interest in the station, he

was

never a stockholder.) In any event, the

combined political influence of Haas and Bone was put to bear on the

newly-organized Federal Communications Commission. It

seems that whenever a U.S. Senator lobbied

the commissioners, locked doors magically opened.

Looking for

a solution to KIRO’s limited-hours problem, Haas and Bone

convinced the FCC to allow KIRO to “temporarily” change frequencies to

710 kHz. 710 was designated as a Class 1-A

clear-channel,

assigned to WOR in New York City. (Class

1-A meant that only one station in the country could use the frequency.) But WOR operated with 50 kW into a directional

antenna that favored a North-South direction, thus sending a lesser

amount of

power westward. Because its signal did

not reach the Western USA, Haas and Bone proposed to the FCC that KIRO

should try

operating on the 710 channel with unlimited hours and 250 watts on a

test basis

to see if any interference to WOR was reported.

The Commission granted the request, issuing a temporary

experimental

permit that was valid for six months.

That “temporary” permit would be extended every six months

for the next

five years! During that time, teams of

engineers conducted extensive tests to document KIRO’s signal coverage,

finding

no instances of interference to WOR.

The KIRO

transmitter was moved in 1936 to the top floor of the Rhodes

Department Store, using an existing rooftop antenna that had recently

been

vacated by KFOA/KOL. The power was

increased to 1,000 watts in 1937. All of

this was, of course, just “experimental”.

Although WOR

had initially agreed to the KIRO tests, it soon had a

change of heart when other Western stations also requested a chunk of

the 710

channel. KMPC in Beverly Hills,

California, which was already on 710 at 500 watts but with limited

nighttime hours

to protect WOR, now requested nighttime operation and higher power. If this was to be allowed, WOR would find itself

demoted to a secondary Class 1-B license status.

Additional pressure was applied in the form

of lobbying by CBS, which wanted better signal coverage for its two

affiliated West

Coast stations. An

additional factor was

the speculation that the FCC would allow certain 1-A clear channel

stations to

operate with increased powers up to half a million watts, a proposal

being floated by some broadcasters after WLW in Cincinnati’s

experimental

operation

at that super-power level. WOR feared

that, by allowing other stations to occupy the channel, its ability to

raise power

would be blocked. Eventually, Congress

became involved in the issue when it held contentious hearings in 1938

to

determine whether or not broadcast power levels above 50 kW would be

allowed. (Ultimately, Congress dictated

to the FCC that 50 kW would be the U.S. power ceiling, and WLW’s experimental

permit

was revoked.)

Another

issue working against WOR’s case was the international

negotiation taking place to re-order the assignment of broadcast

frequencies in

North America (the NARBA treaty). In those

negotiations, the 710 channel was to be re-classified as a 1-B

frequency, which

would allow stations in neighboring countries to use the channel.

In its 1939

article about the NARBA committee hearing, “Broadcasting”

Magazine wrote:

Making an impassioned plea

for the classification of

WOR, Newark, as a Class 1 station of the upper bracket rather than a

Class 1

duplicated station, as recommended by the committee in accordance with

the

Havana Treaty allocations, Frank D. Scott … said the only logical

reason he

could conceive for WOR’s relegation to 1-B status was “an unfortunate

and

undeserved retaliation on WOR for having consented to an

experimentation” of

the experimental use of the 710 kc channel, starting 4 years ago, by

KIRO,

Seattle, to determine whether its service in the Seattle territory

would

interfere with the normal service of WOR.

Reminding the Commission that WOR had withdrawn its

permission for the

use of the 710 kc frequency before the subcommittee started its

hearings, …

although he refused to believe it was an intentional discrimination

against

WOR, “in effect it is a definite discrimination.”

Ultimately, in November,1939,

the FCC officially demoted the 710 channel

to Class 1-B status, clearing the way for a formal modification of

KIRO’s

license to operate full time on the 710 channel, ending the station’s

experimental status. Both WOR and KIRO were given equal

Class 1-B status. At

the same time, KMPC was given a Class II

license with unlimited operation at 5,000 watts days and 1,000 watts at

night.

Those

actions immediately opened the floodgates to other applicants,

and, in 1939 and 1940, stations in Fort Worth, Ft. Lauderdale,

Minneapolis and

Kansas City all filed for the 710 frequency as Class II stations. The applications were set for hearings, but

the start of World War II froze all applications. That

left WOR, KIRO and KMPC as the sole

occupants of the frequency. Eventually,

after the war, the 710 channel was broken down further, with a several

stations

operating around the country as Class II stations, meaning they were

required

to use directional antenna systems that protected both WOR and KIRO.

“If You Can’t Get This

Station, Better Give Up”

As

mentioned, now that KIRO was formally broadcasting on 710 kHz with

1,000 watts, Saul Haas took advantage of the opening to go for even more

power. In February, 1940, he filed an

application with

the FCC to increase KIRO’s power to 10,000 watts using a directional

antenna

that would focus the station’s power north and south along the Pacific

coastline. KMPC at first objected, as it

was also planning to increase power from a new site, but the objection was

removed

when the two stations agreed to protect each other’s signals from

interference.

Shortly after

KIRO’s application was submitted, CBS announced its

intention to drop KVI as its affiliate in Tacoma the following year. KVI had just inaugurated a new 5,000-watt

tower on Vashon Island, giving it a strong signal in Seattle, and

KIRO’s planned

10,000-watt signal would cover Tacoma equally well.

The network now recognized Seattle-Tacoma as

a single radio market, and it did not want two CBS stations

competing for listeners. KVI was to be the loser.

In 1939,

Haas asked Tubby Quilliam to meet with the owners of KVI and

explore the opportunity of buying the station. He hoped to operate both

KIRO

and KVI from the KVI’s Vashon Island property. But

those negotiations went nowhere, and so in

February of 1940 he acquired 37 acres of property on Maury Island,

midway

between Seattle and Tacoma in the Puget Sound, to construct KIRO’s

directional

transmitter plant. In

October, 1940, KIRO modified its FCC application

to request 50,000 watts, which was immediately approved.

KIRO’s chief

engineer James B. Hatfield managed the entire project for

KIRO, dealing with numerous setbacks and unforeseen obstacles. Clearing of the second-growth forested plot

was

complicated by the existence of 600 stumps from the original old-growth

forest,

and it took a road-building crew nearly 4 months to finish the job. The Northwest’s rainy fall and winter weather

delayed the installation of the two towers and the burial of 21 miles

of copper

ribbon that would form the ground system. The

construction of the Art Deco transmitter building couldn’t begin until

the

ground system work was completed. Pre-war

buildups by the Department of Defense delayed

the deliveries of many materials.Western

Electric was the chosen supplier for the transmitting equipment,

and Frank McIntosh, who would later develop a line of high-fidelity

sound

equipment under his own name, became that company’s field engineer for

the

project. When

completed, the KIRO transmitter facility on Maury Island would

consume $182,000 in direct costs, and with ancillary expenses the total

project came in at over $250,000 ($5.3 million in today’s dollars).

At 11:30 AM

on June 29, 1941, KIRO raised its power from 1,000 watts

to 50,000 watts. The

formal dedication of the new KIRO signal It

began at 10:15 AM with a short show by folksinger and future Acres of

Clams

restaurateur Ivar Haglund (1905-1985). Then a dedication preview went

out,

followed by a special “Dedication Edition” of KIRO news. The formal

ceremony at 11:00 AM was broadcast coast-to-coast on the CBS network. It featured officials from CBS, the governor

of Washington State, and the mayors of Seattle, Tacoma, Everett, and other Northwest cities. Afterwards, CBS

saluted KIRO with live music by Lynn Murray and his orchestra. At 1:00 PM, Carroll Foster, voted Seattle’s

most popular announcer, hosted “Looie’s Time Klock Klub”, followed by

vocals by

the “KIRO Dream Girl”, Carola Cantrell. Also

that day, special salutes were heard from

cowboy Gene Autry, CBS orchestra leader Andre Kostelanetz, and mentions

within

several other network programs.

Wartime Radio

KIRO was now

the only 50 kW station north of San Francisco and west of

Salt Lake City - in fact, there were only three others west of the

Mississippi. At the start of World War

II, all station applications were frozen by the FCC, making KIRO the

most

powerful station in the Northwest until after the war.

After Pearl

Harbor, the Pacific Coast was considered particularly

vulnerable to a possible Japanese attack.

Blackouts were occurring periodically on the West Coast,

and the public

could be called on short notice to block out all light outside their

businesses

or residences. KIRO was declared the official northwest station for

bulletins

from 2nd Interceptor Command, and businesses and the public were

advised to

continuously monitor KIRO for these bulletins.

Within days of the declaration of war, the local commander

made a special

request to the FCC to allow temporary non-directional operation at

night, providing

better coverage to Eastern Washington. KIRO

was now on the air 24 hours a day, allowing for the broadcast of

emergency

bulletins at any time.

Because of

the strategic value of the KIRO transmitter during the war,

the government stationed national guardsmen on duty there 24 hours a

day. During construction, with war clouds

on the

horizon, many considerations had been made to protect the station against

wartime

sabotage. The thick concrete walls of

the building held a diesel generator, and a standby shortwave program

link was

put in place, in case phone or power lines to the island were cut. A 120-foot pole was erected outside the

building to serve as an emergency antenna.

KIRO’s

program emphasis during the war years was education.

A full-time education director was hired in

1942, and programs such as “Pledge Allegiance to Your Job” helped

inspire the

patriotic spirit of its audience. There

was also an emphasis on agricultural programming, as KIRO provided

better

coverage to the rural areas than other stations. One

newspaper wrote, “For almost two years,

Bill Moshier’s Farm Forum on KIRO at 7:15 AM has been a ‘must’ on the

radio

calendar of every farm family within earshot of the station.” The program presented technical information

about agriculture as well as farm news of the nation and the world.

During the

war, the CBS network carried on the most aggressive and

thorough war news coverage of any radio organization, led by Edward R. Murrow in London and a

team of

field reporters, nicknamed “The Murrow Boys”, stationed across Europe and

the

Pacific. (Murrow was a Washington native

– he grew up in Bellingham, and received his degree in communications

at

Washington State University. The

communications school at WSU is now called The Edward R. Murrow College

of Communications.)

Due to its

West Coast location, KIRO recorded the daily East Coast CBS

newscasts and special reports onto acetate disks for delayed re-broadcast

at a

more appropriate time. After being broadcast,

the used recordings were stored in the transmitter building. They represented a daily audio journal of the

developing events in the theatres of war.

After the war, KIRO donated more than 2,500 recorded disks

to the

University of Washington, establishing the Milo Ryan Phonoarchive – the world’s most complete library of World

War II newscasts.

Post-War and Television

Under Saul

Haas’ direction, KIRO grew even more after the war. The

studio facilities in the Cobb Building

were enlarged. KIRO-FM 100.7 came on the

air in 1948 – at first broadcasting a duplication of the AM station’s

programs,

but in later years developing into a separately-programmed station. There was a brief experiment broadcasting to

public buses, but KIRO finally settled for simply simulcasting its

regular AM

broadcasts on its FM station.

Since 1948,

there had only been one TV station in Seattle – originally KRSC-TV before becoming KING-TV. An FCC applications

freeze had kept other potential applicants at bay.

When the end of the freeze was announced in

1952, KIRO was planning to file an application for the TV channel 4 that

had been

assigned to Seattle. Realizing that its

studio space in the Cobb Building would not be adequate as a TV studio,

KIRO purchased

the former Queen Anne Club building at 1530 Queen Anne Ave. N. that

year. Built

in 1927, the 12,000 square foot building had a second-floor auditorium

that

could be converted into a TV studio. The

building was remodeled to house KIRO’s radio studios on the first floor

and

offices on the second floor.

But its TV

plans were stalled when competitor KOMO also filed for

channel 4, which would delay both stations' possibilities through drawn-out

hearings

with the FCC. So KIRO agreed to modify its

application to channel 7, the only other remaining VHF TV channel

authorized

for the city, and the FCC then granted channel 4 to KOMO in 1953. But then two other local radio stations – KVI

and KXA – also filed for channel 7. After

a series of hearings in Washington, the FCC decided to award the channel to KIRO

in

1954, but then both competitors appealed. The

contest for channel 7 turned into a deadlock of ugly challenges and

counter-challenges,

with KVI claiming during the Joseph McCarthy “Red Scare” period that

Saul Haas

was a communist sympathizer.

A final decision

in June of 1957 at last awarded KIRO a construction permit

to build a new television tower on Queen Anne Hill.

By this time, six area TV stations already were on

the air - three in Seattle, two in Tacoma and one in Bellingham.

In 1957,

KIRO modified its studio building to accommodate its new TV

studios, and built its TV tower on the south side of the property. KIRO radio and the corporate offices moved

across the street to 1507 Queen Anne Avenue N.

KIRO-TV went on the air February 8, 1958, although

residual KXA and KVI

appeals were still in play until the end of that year.

Because

KIRO had been CBS’s flagship radio affiliate in the Pacific

Northwest since 1937, the two companies had a close relationship.

Saul Haas used his leverage with CBS to acquire the network

affiliation for KIRO-TV. In August,

1957, CBS informed its affiliate KTNT-TV in Tacoma that it would be

moving its programs to KIRO-TV as soon as the new station began broadcasting. KTNT-TV then filed a triple-damages anti-trust suit

against CBS, Queen City Broadcasting, and Saul Haas totalling $15 million,

alleging

restraint of trade and attempt to monopolize.

The lawsuit was ultimately

unsuccessful.

Transition from Dramas to

Deejays

By the

mid-1950’s, TV was king and radio’s “Golden Age” was at an

end. KIRO-TV was a local success, but

KIRO radio was gradually transitioning from the big network programs to

the

recorded music programs of the disc jockey era. Although

stations like KJR and KOL would find

success with Top 40 rock-and-roll programming, KIRO, KOMO and most other

Seattle

stations were offering adult “MOR” music and block programming. In addition to carrying CBS's newscasts and its few remaining

dramatic programs, popular local offerings included the

Clifford and

Clark piano duo in the mornings, “Swap and Shop”, “Maury Rider’s

Turntable Show”,

the “Housewive’s Protective League” with Paul West, and the late night “Dance Time”. There were some notable

successes; during the Korean War, KIRO

broadcast several drives for blankets to send to troops overseas. And in 1956, KIRO won a prestigious Peabody

Award for a community radio series, "Democracy Is You."

In 1959,

KIRO hired Jim French away from KING to be its morning man. His popular show featured a mix of adult music

and French’s polite, conversational style.

In 1966, French moved his

morning

show to a studio on the observation deck of the Space Needle, recently

vacated

by KING’s morning man, Frosty Fowler. The

location gave him a birds-eye view of traffic movement in the city,

which

allowed for accurate and timely traffic reports.

He broadcast from the Space Needle until

leaving KIRO in 1971.

End of the Haas Era

In April of

1963, Bonneville Broadcast, a division of the Church of Latter-Day

Saints, began purchasing stock in Queen City Broadcasting. In January,

1964,

that culminated in Bonneville’s complete purchase of KIRO AM-FM-TV.

Arch Madsen became president, replaced in 1965 by

Lloyd Cooney who headed the station until 1980,

followed

by Ken Hatch. After his retirement, Saul

Haas concentrated his remaining years on the operation of the Saul and

Dayee G.

Haas Foundation , which he formed in 1963 to fund the needs of poorer

students

in the local school districts. Haas

also

served two terms on the board of the Corporation for Public

Broadcasting and

was a member of Bonneville’s board until his death in 1972.

In 1968, a

new “Broadcast House” studio building was constructed for

KIRO radio and TV at Third and Broad Streets. The

previous TV studios at the old Queen Anne

Club building were sold to Community Services for the Blind.

KIRO Newsradio 71

By the

1970’s, KIRO’s ratings as an adult music station were

declining. Finally, in 1974 KIRO switched

formats to a news-talk station, modeled after CBS’s successful KCBS in

San Francisco. It broadcast a three-hour

morning all-news

block hosted by Bill Yeend, and leased an Enstrom helicopter to air the

city’s

first air-based traffic reports, broadcast by Paul Brendle. Hourly CBS newscasts and special reports

augmented the strong local content (except for the 1973-76 period, when

it

switched to Mutual and NBC before returning to CBS.)

The new

format was a quick success, and featured personalities such as Gregg

Hersholt, Wayne Cody, and Andy Ludlum.

Jim French returned to the fold in 1991 as a midday host,

Dave Ross joined

the air team in 1978 as its afternoon anchor, and then moved to mornings after French’s retirement. At different times, KIRO was also the flagship

station for the Seattle Seahawks,

Mariners, UW Huskies, Sounders and Supersonics. KIRO

received the Edward R. Murrow award for

outstanding news programming in 1982, 1989 and 1991.

In the

1990’s, Jim French began producing regular radio drama programs

at KIRO, titled the “KIRO Mystery Theatre”, continuing a pattern he had

previously started at competitor KVI.

The popular programs were recorded before a live audience at the Museum of

History and

Industry and were carried by KIRO on Sunday nights for many years before

going into

independent syndication.

In 1975,

KIRO-FM became KSEA, broadcasting easy listening music to an

adult audience. This was changed to

adult contemporary music in 1990 as KMWX, returning to KIRO-FM in 1992.

In 1993, the

radio and TV newsrooms were briefly combined into a single

operation, but this was scrapped as a failure after only 6 months. .

In 1995,

Bonneville sold KIRO-TV to the A.H. Belo

Corporation. Now separated from its TV sister

station, KIRO AM/FM

moved iout of Broadcast House and nto new studios at 1820 Eastlake Avenue. In

1997, Bonneville sold KIRO AM/FM to

Entercom Communications (now Audacy). But

then ten years later Bonneville re-acquired KIRO

AM from Entercom in a station swap, along with Entercom’s KBSG-FM 97.3. (The original KIRO-FM is still owned by

Entercom, and is now known as country station KKWF “The Wolf”). Back in the driver’s seat, Bonneville decided

to transition KIRO’s successful Newsradio format over to the FM band,

and so

KBSG became KIRO-FM. After a year of

simulcasting its Newsradio programs on both the AM and FM stations, the

transition was completed in 2008 and KIRO AM began a sports format as

“710 ESPN

Seattle”.

Political

clout and shrewd management turned tiny KPCB into today’s AM

and FM juggernaut. The successful KIRO Newsradio format is now nearing its 50th anniversary. Undoubtedly, KIRO is

one of radio’s big success stories.

REFERENCES:

- “Broadcasting”

Magazine, (worldradiohistory.com): 9/1/34,

11/1/35, 11/1/36 ,2/15/37, 3/15/37, 10/15/37,

12/15/37, 4/1/38, 4/15/38, 5/1/38, 6/15/38, 7/1/38, 9/15/38, 11/1/38,

2/15/39, 6/15/39,

7/15/39, 9/1/39, 10/15/39, 11/15/39, 5/1/40, 6/1/40, 8/15/40, 11/1/40,

2/10/41,

7/7/41, 11/3/41, 12/29/41, 1/12/42, 1/21/52, 7/7/52, 6/15/53, 4/11/55,

6/2/58, 12/15/58

- Seattle

Post-Intelligencer 6/21/41

- Seattle

Times 1/6/97

- “History of

KIRO” by David Braun, Puget Sound Antique

Radio Association

- Saul Haas

biography, HistoryLink.org

- FCC History

Card for KIRO, www.fcc.gov

- KIRO

historical files of the FCC at the National

Archives, Washington, DC

- Personal

files of James Hatfield, courtesy of his son

Jim Hatfield Jr.

- “Good Night,

Chet,

A Biography of Chet Huntley” pages

28-30

- "Moodys

Analyses of Investments 1917” – Coast Biscuit

Co.

- KIRO Silver

Anniversary Brochure, 1952

- Queen Anne

Historical Society, https://www.qahistory.org/articles/queen-anne-club

- Wikipedia: KIRO,

KPQ, Moritz Thomsen

|