The History of KFRC San Francisco

and the Don Lee Networks

By

John Schneider, W9FGH

Copyright 1997

www.theradiohistorian.org

Copyright 2015 -

John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC

(Click on photos to enlarge)

KFRC's

original

station

license application from

Department of Commerce files, 1924

KFRC's first studio, in the City of Paris Department Store, 1925

Harrison Holliway, founder and

Manager of KFRC

Young Harrison Holliway operating his ham radio station, 6BN

The Whitcomb Hotel -

KFRC's first home

The Don Lee Cadillac Building,

exterior view

The Don Lee Cadillac Building,

showroom view

The KFRC transmitter in the Don Lee

Cadillac Building, 1930s.

The Cast of KFRC's

Blue Monday

Jamboree, 1927

Harrison Holliway announcing on

KFRC's "Jamboree", 1927

Al Pearce, of KFRC's

'Happy Go Lucky

Hour'

Cast Photos of KFRC's

'Happy Go Lucky Hour'

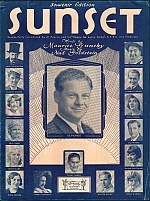

Sheet music for the song "Sunset",

introduced on the "Happy Go Lucky Hour" on KFRC

Meredith Willson, KFRC's

Music

Director, 1929

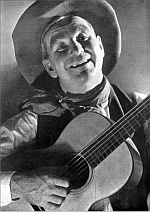

'Haywire Mac' McClintock of KFRC's

"Mac and His Gang", 1920's

Tommy Harris, KFRC's 14-year-old

star

vocalist, 1932

Edna Fischer, popular KFRC pianist

Comedian Morey Amsterdam

on KFRC

Merv Griffin began his career

as a KFRC staff vocalist

Governor James Rolph

at KFRC, 1932

Ernie Smith football broadcast

on KFRC, 1930

Competition with

Earle C. Anthony

Ruth Anderson, KFRC Newscaster

The city of San Francisco had several stations that were among the finest in the nation during broadcasting's early years. Bay Area listeners could choose from a variety of fine programs, but one station they tuned to most frequently was KFRC.

HARRISON HOLLIWAY:

To tell the story of KFRC's first years is to tell the story of its Manager

and Chief Announcer, Harrison Holliway. He was born November 3, 1900, the

first son of a veteran San Francisco newspaperman, Captain W. C. "Cap"

Holliway. Cap Holliway was well-known in San Francisco, and at one time

had been the youngest newspaper editor in the state. He had since worked

on news staffs at the Examiner, Call and Chronicle, and had been President

of the San Francisco Press Club.

Young Harrison's first interest in radio appeared at the age of eleven, when he built a carborundum crystal receiver and first listened in on the airwaves. By 1920, he was operating his own amateur station, 6BN, and was very active in local ham circles. He was President of the Lowell High School Radio Club, and an officer in the San Francisco Radio Club. In 1920, he set a world amateur record for distance in voice transmission when he communicated with another ham in Vancouver, over 1,800 miles away. This brought him considerable local publicity. For a time, Harrison was on the air every day with 6BN, broadcasting record programs "for the sheer pleasure of it". He also worked as a part-time newspaper reporter, covering high school sporting news for the San Francisco Call.

The following fall saw Harrison Holliway enter Stanford University. He spent the next few years majoring in law during the winter months, and operating radio equipment on a trans-Pacific steamer during the summer. He took a leave of absence from Stanford in 1922, and, along with friend Harold Shaw, installed and operated KSL, the Emporium Department Store station. When that venture folded after less than a year, he went back to Stanford.

THE DEBUT OF KFRC:

The summer of 1924 found Holliway working at a radio shop called the Radio

Art Corporation, on Sutter Street at Powell. That was the same summer that

a Western Electric salesman called on the owners of the store, Jim Threlkeld

and Thomas Catton, and sold them on the idea of starting a new radio station

(and of course, buying a Western Electric transmitter). And so, KFRC was

born. Holliway couldn't resist the offer of the job of Station Manager,

and never returned to Stanford. He and two other store employees, Harold

Peery and Alan Cormack, began drawing up their plans for the station.

KFRC's first home was the Whitcomb Hotel in the Civic Center area. The studio was a converted hotel room on the second floor -- a single room hung with "monk's cloth", decorated with a few shaded lamps, and with a lone microphone and a piano. The transmitter was located in a shack on the roof of the hotel, and an L-type antenna was suspended between two 100-foot ships' masts. KFRC's assigned frequency was 1120 kc. The transmitter itself was a fifty watt unit, the latest Western Electric design. The only other one like it was in St. Louis, where it was said to "pound into New York like a local. The relatively low-powered transmitter was said to be preferred by the station engineers because it would cause less interference and yet deliver almost equal signal strength because of its superior circuit design.

KFRC became the official station of the "San Francisco Bulletin", which supplied it with a news service and a radio column in exchange for the broadcast publicity. The station's on-air trademark was a fire siren, chosen because it had also been used by station KDN before it left the air, and when it had been associated with the Bulletin.

KFRC's inaugural broadcast took place September 24, 1924, from 8:00 PM until midnight. The program opened with speeches by local dignitaries, and was followed by a concert and dance program by the Whitcomb Hotel concert, symphony and dance orchestras.

Almost immediately, it was noticed that KFRC had an exceptionally strong signal -- much stronger than had been anticipated from only fifty watts. It was heard in all the distant places being reached by only the strongest stations: along the Atlantic Seacoast, in Alaska and Hawaii, and even New Zealand. This had San Francisco's best engineers dumbfounded. No one could understand why the signal was so powerful, and it was announced that "the KFRC managers ... are as astonished as anybody." A group of Western Electric engineers was called in to study the situation, and after several months could still not agree on an answer, except that perhaps the Whitcomb Hotel was located on an essentially "perfect" electrical ground.

KFRC's first year of radio activity was nothing exceptional. The station's owners, Catton and Threlkeld, had formed the Radio Art Studios as a subsidiary of the radio store, and it was entirely financed by the retail operation. Budgets were modest, and so were the programs. Perhaps the only noteworthy regular program heard at this time was a variety program hosted by Tom Catton and called the "Tom Cats".

Holliway, who in the first year of KFRC was Manager, announcer, janitor and mail clerk all rolled into one, later recalled some famous personalities of the time whom he interviewed during the early years. They included baseball great Roger Hornsby, and actors William S. Hart, John Barrymore and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. Speaking of the French-Canadian heavyweight boxer Jack Renault, Holliway said:

Renault came to the studios with his manager, the well-known Leo P. Flynn.

He spoke very broken English, and at the same time developed a bad case of

mike fright. Flynn did the French-Canadian dialect to perfection, so I

introduced him as Renault. He made a fine speech, and no one ever knew

that it wasn't Renault whom they heard.

THE CITY OF PARIS YEARS:

It was less than a year later that Radio Art Studios was forced to relinquish

KFRC for financial reasons. The station was transferred to the City of Paris

department store on April 15, 1925, and the facilities were moved to the

store on Union Square, where a studio had been constructed at street level,

so passers-by could observe the operations through a large window. A year

later they were moved again, this time to the eighth floor of the Sherman-

Clay Building.

With the addition of City of Paris financial backing, KFRC's programs improved immediately. Frank Moss, a nationally-known pianist, was hired as the Musical Director and given the budget needed to round up first-class talent for a number of new programs. Several musical groups became KFRC regulars, most notably the Lorelei Mixed Quartet and soprano Flora Howell Bruner. KFRC was broadcasting almost exclusively serious music.

Another popular name associated with KFRC was Harry "Mac" McClintock, who hosted a daily children's program called "Mac and his Gang". Mac's homespun manners and cowboy ballads quickly became popular among the Bay Area's young crowd. His prior life best exemplified the kind of person he was: he had left his home in Tennessee as a boy and joined the circus. After fighting in the Spanish-American War, he headed for the Klondike and the Alaska gold rush. He had also worked as a railroad brakeman and as a miner in Idaho, Wyoming and Nevada. From these experiences he drew upon a wealth of Western songs and stories that made him a favorite with adults as well as children, and his style was often compared to that of Will Rogers. Among the many other feathers in his wester cap, Mac wrote and popularized the song "Big Rock Candy Mountain". His comic western band, Mac and his Haywire Orchestry, was frequently heard on KFRC's variety programs.

THE DON LEE ERA:

Perhaps it may be considered to be the re-birth of KFRC (it certainly marked

a future of bigger and better things) when Don Lee, the California distributor

for the Cadillac Motor Car Company, purchased the station in 1926. Lee had

amassed a considerable fortune in his twenty years in the automobile business,

and radio was to be an exciting and elaborate new venture for him. On an

evening broadcast heard November 15, 1926, officials of the City of Paris

formally turned over the station to Don Lee, and the audience was told of his

plans for a great station to broadcast from new and elaborate studios he planned

to build in the Cadillac building. He had a personal habit of doing everything

in grand style, and this was to be his hallmark for the twenty five years he would

own the station.

Temporary studios were soon built and installed in the Don Lee Building at 1000 Van Ness Avenue. The transmitter remained in its original location atop the Whitcomb Hotel, but plans were under way for an elaborate new studio complex and a 1,000 watt transmitter.

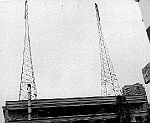

The new studios were completed and dedicated in a 28-hour marathon broadcast held July 6, 1927. The station was located on the mezzanine floor of the building, at the end of a large and ostentatious staircase leading up from the showroom floor. Two large studios had been decorated in a spanish motif, and they were said to be so acoustically perfect that a full orchestra could be on the air in one studio while a second group rehearsed in the adjoining one. The thousand-watt Western Electric transmitter on the top floor of the building fed a powerful new voice to the new antenna, strung between steel towers on the roof. As a higher power, Class "B" station, KFRC was authorized to move to the preferred frequency of 660 kc. (two years later, the station again moved, this time to its permanent home at 610 kc.) On its new frequency, KFRC was required to reduce its power to 500 watts after sunset.

The old 50-watt KFRC transmitter saw use for a while as a short-wave relay of KFRC's AM programs. Harrison Holliway and Harold Peery rebuilt the unit to operate on 108 meters, and the station received the experimental call sign 6XD. Originally, their plan had been to use the new station to transmit details of the Dole fliers in their trans-Pacific flight from Oakland that year, a plan later abandoned. But the station was operated for a while and heard as far away as Juneau, Alaska. [16]

The following year (November 14, 1927), Don Lee bought KHJ in Los Angeles from the Los Angeles Times. The station was relocated to the Don Lee Cadillac Building at Seventh and Bixel Streets in that city, where a new radio facility was built,stocked with all the finest new equipment. There were three elaborate studios including a full pipe organ.

Being the owner of two of the Coast's most prestigious radio stations, Don Lee wasted no time in connecting the two stations by telephone line to establish the Don Lee Broadcasting System. Lee spared no expense to make his two stations among the finest in the nation, as a 1929 article from Broadcast Weekly attests:

Both KHJ and KFRC have large complete staffs of artists, singers

and entertainers, with each station having its own Don Lee

Symphony Orchestra, dance band and organ, plus all of the musical

instruments that can be used successful in broadcasting. It is no

idle boast that either KHJ or KFRC could operate continuously

without going outside their own staffs for talent, and yet give a

variety with an appeal to every type of audience.[2]

In 1929, the nation's second network, the Columbia Broadcasting

System, still had no affiliates west of the Rockies, and this was

making it difficult for the network to compete with its larger rival,

NBC. CBS president William S. Paley was in need of West Coast

affiliates, and he needed them fast. Thus it was that Paley travelled

to Los Angeles that summer to convince Don Lee to sign a CBS affiliate

agreement. Paley was a busy man, and he was frustrated by Lee's

casual, time-consuming ways of doing business. Lee insisted that

Paley spend a week with him on his yacht "The Invader" before any

business could be discussed. After two lengthy sailings during which

Lee had plenty of opportunity to evaluate Paley's moral fiber in the

relaxed, informal atmosphere at sea, Lee agreed to sign an affiliate

agreement which Paley was to dictate without any negotiation

whatsoever. The agreement was signed on July 16, 1929, and the Don Lee

stations became the vanguard of the CBS West Coast invasion. [3]

In Paley's statement to the press announcing the new venture, he said:

I know the new connection of the Columbia System on the Pacific

Coast will react as a mutual benefit to the listeners in that

territory and ourselves. These Pacific Coast stations have not been

chosen to join the Columbia System on hearsay evidence, or on cold

statistics alone. I personally toured the Coast during June and

July of this year, and was convinced that through years of service

to a faithful radio audience, the stations chosen are outstanding.

It is with great pleasure that I am able to announce that they will

be our western brothers in the world's largest regular radio network.

Don Lee's companion announcement stated: With the growth of public interest in radio, we believe the

affiliation of these stations with the Columbia Broadcasting System

will be welcomed by radio fans not only on the Pacific Coast, but

throughout the United States as well. It will enable us to listen to

the finest programs from the East, and will permit the Easterners to

get the best of western programs.

The new chain began operations January 1, 1930, and was called the

Don Lee-Columbia Network. Two more stations, KGB in San Diego and

KDB, Santa Barbara, were purchased by Don Lee and became a part of the

network. Also, Lee had been feeding programs to the McClatchy

Newspaper station KMJ in Fresno since 1928, and that station became

a CBS affiliate, along with the other McClatchy stations (KFBK

Sacramento, KWG Stockton, and KERN Bakersfield). Additionally,

four Pacific Northwest stations called the "Columbia Northwest Unit"

were added (KOIN, Portland, KOL, Seattle, KVI, Tacoma, and KFPY

Spokane).[4]

KFRC and KHJ originated numerous programs for the West Coast network. CBS programs were heard in the early dinner hours, and the Don Lee programs were fed after 8:00 when the eastern programs ceased.[5] For these later evening broadcasts, KFRC and KHJ alternated evenings in feeding their programs to the network. Additionally, several of the San Francisco and Los Angeles programs were broadcast nationally by CBS. Many of the most popular KFRC programs became network offerings in this way.

Perhaps one of the most notable aspects of KFRC and the Don Lee System during this period is the large number of people they graduated to national stardom. In 1929, Lee hired an unknown flutist to be KFRC's Music Director. The young man was a musical prodigy, having played with John Phillip Sousa's band at age 16, and he had been the lead flutist for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra at twenty. Now, he was to get a chance to conduct the Don Lee Studio Orchestra in San Francisco. To Meredith Willson, "The Music Man", radio would be the springboard to big and better things.

Jack Benny's announcer Don Wilson also began his radio career at KFRC as a member of the "Piggly-Wiggly Trio". Manager Harrison Holliway was impressed with Wilson's voice, and asked him if he wanted to try his hand at announcing. He only snickered and mumbled something to the effect that he wasn't going to become a "cream puff". Ralph Edwards and Art Van Horn were also announcers; so was Mark Goodson, who had a knack for quiz shows. He had several on the Don Lee Network, such as "The Quiz of Two Cities" and "Pop the Balloon" before he left for New York and teamed up with Bill Todman. Art Linkletter was a staff member in KFRC's later years, and hosted a series of programs from the San Francisco Treasure Island World's Fair in 1939, as did announcer Mel Venter. Bea Benederet was San Francisco's famous lady announcer. Harold Peary and Morey Amsterdam both began their radio acting careers at 1000 Van Ness Avenue, and Juanita Tennyson and Merv Griffin were popular staff vocalists; John Nesbitt began his "Passing Parade" at KFRC. The list is endless ....

AL PEARCE:

One of the most successful performers to come out of KFRC was Al Pearce.

Al, a native of San Jose, had always been a born entertainer, having

first stepped before the microphone in 1916. The occasion was the Panama

Pacific International Exhibition in San Francisco, where radio pioneer Doc

Herrold was operating an experimental radio broadcasting station (later to

become KQW). As Al once told a reporter: In 1916 I sang on KQW. We were trying to demonstrate that radio

could be heard overseas. I sang "Hello Hawaii, How Are Yuh?"

(In those days, we pronounced Hawaii, "Huh-why-yuh".) The only

thing that picked us up was the U.S.S. Sherman, fifty miles off

shore!

His guitar and songs had been strictly a hobby until the mid 1920's, when

his real estate business suddenly failed. A KFRC executive saw he and his

brother Cal performing a vaudeville sketch at a real estate convention,

and they were immediately hired. Their program on KFRC, "The Happy Go

Lucky Hour", first debuted in 1929.

Alice Blue, KFRC staff organist, wrote of her recollections of Al Pearce's

beginnings: The Gang was developed from a small program of three KFRC staffers,

who had no idea what they had spawned -- Norman Neilsen, Monroe

Upton and I. Norman sang ballads, Monroe emceed and I played the

piano -- preceding Edna Fischer. We had a daily program -- no

name -- in 1929 when we were all pretty much on our own without

the regulations that came later. The small program grew and grew.

Fan mail poured in and still we didn't really realize what we had.

One day, Al Pearce walked in and said 'This is it.' He had an eye

and an ear for show business. Soon our threesome had a cast that

later included the original trio out. One time many years later I

sat next to Al at a dinner and he drank a toast to the lost trio

who started the ball rolling. It rolled far under Al's clever

management.

"The Happy Go Lucky Hour" was a vaudeville-style variety show, featuring

music and comedy skits with a cast of regular entertainers. There was

singer Tommy Harris, Upton, who played the character "Lord Bilgewater",

Harry "Mac" McClintock, Hazel Warner, Edna O'Keefe, Marjorie Lane Truesdale,

Tony Romano, Abe Bloom, Cecil Wright and a host of others.

Al's most popular character was the bashful door-to-door salesman Elmer Blurt, whose knock on the door was always followed by the familiar line, "There's nobody to home today, I hope, I hope, I hope". Another was Miss Tizzie Lish, known for her bad recipes and good gags.

The popular program graduated from a West Coast offering to nationwide on

CBS. It moved to NBC in 1933 and became "Al Pearce and His Gang", a

network staple until 1947. (Brother Cal never made the move to the

networks, and returned to his previous career of real estate.)BLUE MONDAY JAMBOREE:

At KFRC, in addition to their own program, the Pearce Brothers were heard

as regulars on another program, "The Blue Monday Jamboree". This was

the most popular West Coast program ever to come out of KFRC, if never as

great a sensation nationally as Al Pearce. The Jambouree was Manager

Harrison Holliway's own creation. It was a studio musical and comedy

extravaganza first heard January 10, 1927. The program began as a fifteen

minute feature heard Monday evenings at 8:00. Public acclaim was so sudden

and overwhelming that by February 7, less than a month later, it had been

expanded to two hours.

Here's how the Oakland Post-Enquirer described the "Blue Monday Jamboree":

The weekly frolic attracts more listeners probably than any other local program. Now an institution, the Jamboree each week parades the import personalities of the station before the microphone for two hours. The important factor that makes the Jamboree attractive is its spontaneity. Listeners never know what is coming next, and the surprise element adds auditors.Another newspaper, the Los Angeles Inside Facts, added:It's a treat to watch the Jamboreeadors in action -- Frank Moss wearing his hat; stars standing behind a roped section waiting their turn to perform; Simpy Fitts playing a tune with a knife and fork on a plate borrowed from a nearby restaurant; Harrison Holliway wondering what Schnitzel or Eddie Holden, the Japanese, is going to ask him next; the Pearce Brothers, ever ready with an idea; Charles Bulotti, singing for the fun of it, leading a burlesque opera group; and some sixty or seventy people seated in the studio already crowded by a large orchestra, Mac's Gang and the artists.

The studio itself is packed way out to the sidewalks on a Monday night, when an invited list of guests attend for a first-hand glimpse of their favorite entertainer, and are surprised to learn that Al Pearce, who sings "Barnacle Bill" in a high register, is a six footer; that Cotton Bond is not colored but white, and that Frank Watanabe is not a Japanese houseboy, but just Eddie Holden under another name.The program was one of the first variety shows -- a vaudeville production on the radio. During most of its existence, it claimed the vast majority of Bay Area radio dials. When KFRC was joined with KHJ, it was one of the first programs from San Francisco to be heard in Los Angeles, and its following in that city quickly equalled its northern counterpart. On June 7, 1930, the program made its debut on the entire Don Lee-Columbia Network, and by the end of the year, was being heard nationally on CBS. In California, the names Blue Monday Jamboree and Golden State Milk, the regional sponsor, became synonymous.

Holliway told a reporter in 1929 how the program was produced:

Preparation for this program starts Tuesday morning, nearly a week before it will be presented. The staff begins to talk things over, making suggestions for comedy and discussing available music. They are searching for something out of the ordinary.The Jamboree was literally Holliway's own program. He had devised the original concept, and wrote, directed and emceed the program, as well as playing frequent bit parts. Throughout his tenure at KFRC, the program remained his pet project.They must provide episodes for Pedro, Frank Watanabe, Silas Solomon, Professor Hamburg and Simpy Fitts, all characters who participate on the broadcast. Suggestions and ideas come from all sides; a few do the actual assembling. In the matter of music, it is much the same. If it isn't a new number, the arranging department provides a new arrangement for it. Those in charge see to it that individual numbers fit into the program as a whole.

Finally, the entire program -- announcements, "gags", musical numbers and continuity -- is typewritten and rehearsed. Nothing is done "ad lib". As a consequence, the listener hears a program which goes off smoothly, works up properly to climaxes, and has proper music to fit the occasion.

One of the regulars on the Jamboree was a comedy team called Murray and

Harris: Murray Bolen and Harris Brown. Bolen, later an executive with a

Los Angeles advertising agency, told of his experiences with the program:

As to Murray and Harris at KFRC -- we got there in 1929, and left

seven years later after riding through a wonderful time for radio.

Harris Brown and I had been to prep school together, went different

ways through college, and met again six years later by accident.

I was an announcer at KFI (1928) and Harris came into the station

to perform in another musical act. He was astounded at our chance

meeting, and influenced me to join him as a partner and leave the

announcing biz. We rehearsed up an act and went on the road

(vaudeville) and to KJR, Seattle, for a year. That went broke, and

we came south to San Francisco via Orpheum vaudeville. There we

re-met a friend, Meredith Willson, musical director, and he helped

get Harrison Holliway to put us on KFRC's Jamboree and the Happy

Go Lucky Hour. In 1929, we were a real great success, and radio

was a big thing. We "personally appeared" all over the West, and

generally whooped it up, along with the whole gang up there.

Personal appearances for the Jamboree were frequent. Not unusual was the

week of May 31, 1929, when the entire troupe played 23 performances to

audiences at the Pantages Theater in San Francisco.

Another popular follow-up to the "Blue Monday Jamboree", called the "Midnight Jamboree Revue", was a vaudeville variety program heard weekly from midnight to 2 AM. It was broadcast with the express purpose of reaching listeners in distant cities. The program was heard beginning May 7, 1928.

Still another interesting KFRC program was "The Lady of the Clouds" with

Yvonne Peterson. On this program, Miss Peterson sang and played her

ukulele from the passenger seat of an airplane as it flew over the city.

A short-wave transmitter was used to relay the signal to the ground where

it was re-broadcast. The show was first heard in 1928, but was short-lived.COMPETITION WITH EARL C. ANTHONY:

One of the prevailing attitudes at all of the Don Lee stations was the fierce

sense of competition between Don Lee and Earl C. Anthony. Like Lee,

Anthony was the Packard distributor with locations in San Francisco and Los

Angeles. And, he also invested in radio with his two Los Angeles stations, KFI

and KECA. Of course, the feeling of competition wasn't as fierce in San

Francisco as it was at KHJ, but it was still very much a factor. The most

glaring reminder of Anthony's competition was his auto dealership, located

almost directly across the street from the Don Lee Building, in an empressive

edifice with marble columns. The competition was so intense that, because

KFRC's antenna was atop the Don Lee Building, Anthony had to have one on top

of HIS building! Thus, a giant radio antenna was constructed, and the letters

"KFI" mounted on the towers. Of course, there was no station attached to the

antenna, but it was a fine antenna.

Paul C. Smith, later a broadcast arts instructor at the California State University at San Francisco, told an interesting anecdote in connection with the dummy antenna. In his early teens he had become fascinated by radio, and had just finished a tour of the KFRC facility when he spotted the Anthony towers. He crossed the street to the showroom and asked to see the radio station that was attached to the towers. The salesman on the floor smiled and said, "I'll show you what's attached to those towers". He led Smith up the grand mezzanine staircase and to the back of the building. He showed Smith into an office where a wire protruded from the wall and led to the back of a little Remler Scotty radio. "But the sign says KFI", Smith protested. "Right", said the salesman, "and it picks up KFI really well!"

(The KFRC antenna was dismantled in 1958, when the transmitter was moved to

Islais Creek. But, the KFI towers stayed until 1972. It was ironic that

the last of the scores of old-style T-type antennas once scattered about

San Francisco was the only one never actually used for broadcasting.)THE MUTUAL-DON LEE NETWORK:

Don Lee died suddenly of heart failure on August 30, 1934, at the age

of 53, and Lee's son Tommy became president of the network.[9] This

presaged a series of events which completely restructured network

broadcasting on the West Coast over the next three years. CBS was

apparently becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the structure of

its western network. The affiliation between CBS and Don Lee, which

had been a convenient mechanism for Paley to add affiliates quickly in

1929, was becoming a source of friction as CBS sought more and more

control over its affiliates and programming. Apparently this friction

even preceded Lee's death.[9] In any event, it came to a head March 19,

1936, when CBS consummated its purchase of KNX in Los Angeles for

$1.25 million. This was the highest price ever paid for a radio

station to that time. The acquisition of KNX gave CBS a 50 KW clear

channel network-owned facility in an increasingly important market.

As mentioned previously, Hollywood-originated programs were becoming

highly sought after by the radio public, and KNX would become the

springboard for a major CBS West Coast program origination effort.[10]

(The network's new studios, Columbia Square in Hollywood, were

officially dedicated April 30, 1938.[11])

Of course, the acquisition of KNX by CBS completely destroyed any remaining relationship with the Don Lee network. The purchase meant that KNX would replace KHJ as the CBS affiliate in Los Angeles. KNX had been sharing a number of programs with KSFO in San Francisco, so it was natural as well for the CBS affiliation in the northern city to transfer from KFRC to KSFO. In fact, CBS soon announced it had leased KSFO with a later option to purchase the station outright.[12] (When that deal later fell through, CBS instead purchased KQW in San Jose, which became KCBS.) The entire structure of the Don Lee Network quickly collapsed. The McClatchy stations lost no time in joining with Hearst stations KYA San Francisco and KEHE Los Angeles to form the short-lived California Radio System.[14] The Northwest station group opted to remained with CBS.

As luck would have it, that same year a fledgling eastern network

called the "Quality Station Group" had changed its name to the "Mutual

Broadcasting System" and was rapidly seeking westward expansion.

Tommy Lee contacted Mutual and lost no time in signing an agreement,

and the Mutual-Don Lee Network was born. This was how Mutual became

the fourth coast-to-coast network, and it also marked the beginning of

a new West Coast chain that would continue operation into the fifties.

The switch from CBS to Mutual was scheduled for December 29, 1936, the

date which marked the expiration of the CBS/Don Lee contract. (In

fact, for the last three months of the contract the CBS West Coast

programs were produced at KNX and fed to KHJ for transmission to the

network.[13] The stations on the new Mutual network were the four Don

Lee-owned stations, plus KFXM San Bernardino, KDON Monterey, KXO El

Centro, KPMC Bakersfield, KVOE Santa Ana, and KGDM Stockton.[15] Also

joining the network via shortwave hookup were KGMB Honolulu and KHBC

Hilo. (A number of Pacific Northwest stations were added the

following year.)CHANGES AT KFRC:

These upheavals had a major impact on KFRC as a radio production

center. The CBS network feeds from the East had reached the West

Coast at San Francisco, and branched north and south from there. This

had made KFRC the key CBS West Coast station. But the new Mutual

hookup reached the coast in Los Angeles, and KHJ became the key

station. In the shake-up that followed these changes, most KFRC

performers were either moved to KHJ or departed for other stations or

networks.

One of those greatly upset by the restructuring was Harrison Holliway, as Murray Bolen related:

H. H. did not necessarily approve of the deal, and felt it a

down-grade. But not only that, it meant that the "key" station

of the West would be KHJ in Los Angeles, no longer KFRC ... and

he would no longer be number one. Also, his biggest pet program,

"The Blue Monday Jamboree", was ordered to L. A. for origination

and became "The Shell Chateau" (with Al Jolson). So, everything

was kind of blowing up, and in 1935 he was offered the top of

NBC's biggest station, KFI, and he took it. It all made good

sense to move. He was ready for the "big time", and that was

starting in L.A. He simply grew more and more, and brought KFI

to the peak of popularity with programming and management.

Earl Anthony, ever the rival of the Don Lee organization, had seen a chance

to steal away one of its most valuable people, and he took advantage of it. Holliway

became nationally known at KFI for some revolutionary management

concepts. He continued there until 1942, when he died suddenly at the

age of 42.

Holliway's replacement at KFRC was Tom Brenneman, a KFRC performer. He was soon superceded by Fred Pabst, a big wheel in the Don Lee heirarchy. Pabst guided the station with stern reins into the fifties, and then made a name for himself in local television.

Following the shake-up at KFRC, and under the guidance of Fred Pabst, a new KFRC appeared. During the late 30's and 40's, it remained among San Francisco's very favorites. Meredith Willson had moved to NBC, and he was replaced by Claude Sweeton. His nightly orchestral broadcasts became a San Francisco tradition, as did the nightly broadcasts of Anson Weeks' Orchestra from the Peacock Court of the Mark Hopkins Hotel. Tommy Harris, a 14-year- old vocalist who had appeared on the old 'Happy Go Lucky Hour', was another KFRC favorite. He and Joaquin Garay were regulars on "Feminine Fancies". (Harris later moved to NBC, as so many from KFRC had done before him, and for many years operated his own night club, 'Tommy's Joynt', on Van Ness Avenue.)

Another KFRC favorite during this period was the

"Hodge Podge Lodge" with Bob Bence. Still later years saw the lasting

popularity of Jack Kirkwood's "Breakfast Club", which continued into the

fifties as one of San Francisco's best offerings.POST SCRIPT:

RKO-General acquired KFRC from the Don Lee organization in 1949. It

operated as a personality-based middle of the road music station into

the mid 1960's, without great success.

In the mid 1960's, KFRC changed to a Top 40 rock'n'roll format, and quickly became the dominant station in the region with that format through the 1970's, featuring the tight, carefully programmed sound developed by RKO-General's star programmer, Bill Drake.

With the decline of the Top 40 format by the end of the 70's, KFRC's programming was changed to feature a 1940's big band nostalgia format, known as "Magic 61". In the 1990's, KFRC continued with a nostalgia format, but this time serving the next generation, and playing the rock hits of the 1960's and 70's, recreating the successful Bill Drake years.

REFERENCES:

Interview between author and Alan Cormack, former KFRC Chief Engineer.

San Anselmo, California, December 1, 1970.

San Francisco Bulletin, Sept. 23, 1924

San Francisco Call, September 15, 1926

San Francisco Call and Post, July 6, 1927; August 20, 1927

San Francisco Chronicle, April 24, 1957; June 3, 1961; June 12, 1961

[1] Douglas, George H., The Early Days of Broadcasting, (McFarland & Co.,

Inc., 1987), page 140.

[2] Broadcast Weekly Magazine, 8/24/29, page 18.

[3] Paper, Lewis J., Empire: William S. Paley & the Making of CBS, (St.

Martin's Press, New York, 1987), page 35.

[4] 1935 Broadcasting Yearbook, Broadcasting Publications, Inc.,

Washington, D.C.

[5] "KFRC, KHJ To Join CBS", Broadcast Weekly Magazine, 8/24/29, page 18.

[6] Various clippings from the scrapbook of Harrison Holliway, former

KFRC manager; unpublished; loaned to the author by Holliway's former

associate, Murray Bolen.

[7] Letter to author by Murray Bolen, Hollywood, California, 4/14/71.

[8] KFRC Press Release, dated 10/14/70.

[9] Broadcasting Magazine, 9/15/34

[10] Broadcasting Magazine, 4/1/36

[11] Broadcasting Magazine, 5/1/38

[12] Broadcasting Magazine, 6/1/36

[13] Told to author by Art Gilmore, former CBS announcer, 6/2/90.

[14] Broadcasting Magazine, 12/15/36

[15] 1938 Broadcasting Yearbook, Broadcasting Publications, Inc.,

Washington, D.C.

[16] San Francisco Call and Post, 8/22/27, page 8

Interview between author and Arman Humburg, veteran KFRC

engineer. San Francisco, California, October 9, 1970.

Untitled KFRC history summary. Unpublished; from KFRC's

historical files.

The Federal Radio Commission Station List, as authorized on 11/11/28.

From resarch by Barry Mishkind, 1993-94.

www.theradiohistorian.org

John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC

Copyright, 2015