SEATTLE RADIO HISTORY:

KJR AND KOMO

By John Schneider, W9FGH

www.theradiohistorian.org

Copyright 2011 -

John F. Schneider & Associates, LLC

(Click on photos to enlarge)

Vincent Kraft founded KJR in 1919 as amateur station 7XC. It was the first radio broadcasting station to be licensed in the Pacific Northwest.

KJR Studios in the Terminal Sales Building, 1924.

KJR's Transmitter in the Terminal Sales Building, 1924.

KJR's 5 kW transmitter on 15th Avenue NE, 1925. Chief Engineer Clarence Clark is pictured.

KJR newspaper publicity page, 1928.

Adolph Linden, who built KJR into one of the West Coast's finest stations, and then went to jail for embezzling the money to pay for it.

Homer Pope worked at KJR from 1927 to 1970.

KJR's Studio "A" in the Home Savings Buuilding, 1929.

A network map shows the American Broadcasting Company's affiliate stations in 1929.

KJR's Mardi Gras Gang, regular performers on the ABC network in 1929.

The Gauchos, another band in the KJR studios, about 1931-32.

KJR announcer Thomas Freebairn-Smith

KJR sports announcer Bob Nichols, 1927.

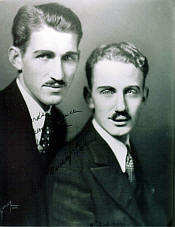

The comedy team Murray and Harris appeared on KJR in 1929.

KJR band leader Victor A. Meyers broadcast from the Rose Room of the Butler Hotel over the ABC network in 1928-29.

Francisco Longo was the director of the American Salon Orchestra on the ABC network in 1929.

A KJR QSL card from the 1920s.

Roy and Elise Olmstead, 1925.

Federal Agents surround the Olmstead residence, 192516.

Elise Olmstead broadcasts as "Aunt Vivian" on KFQX.

Nick Foster operates the KFQX transmitter, 1924.

Birt F. Fisher, who turned KFQX into KTCL, and later opened KOMO.

A KOMO studio engineer in the Skinner Building, 193716.

A KJR program is broadcast from the Skinner Building.

Floor plan of the KOMO-KJR studios in the Skinner Building.

Two views of the KOMO-KJR transmitter site in West Seattle, 1936.

The KOMO-KJR staff, 1937

The KOMO-KJR management, 197.

Post-Intelligencer sports editor and Seattle icon Royal Brougham interviews boxer Jack Dempsey on KOMO.

The cast of "Narratives at Nine", heard weekly on KJR.

KJR reporter Charles Herring.

Popular KJR personalities of the late 1940's.

Dick Keplinger was a popular KJR news reporter in the 1940's, and later was a fixture on KOMO-TV

.O.D. Fisher and Birt Fisher preside over the separation of the KJR and KOMO ownership iin 1942.

The KJR staff at the station's annual Christmas party, 1947.

Reporter Bob Ferris with a KJR news vehicle and early wire recorder, 1947.

KOMO building and TV tower on Denny Way, 1948.16

KOMO's RCA BTA-50B AM transmitter on Vashon Island, 1995.

Under Lester Smith's stewardship, KJR rose to capture 37% of the Seattle audience.

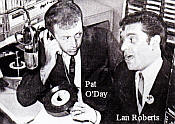

Pat O'Day and Lan Roberts, two of KJR's most popular disk jockeys in the 1960's.

KJR disk jockeys Jerry Kaye and Larry Lujack.

KJR hosts popular rock and roll performers in the mid 1950's.

THE BEGINNINGS OF KJR

KJR in Seattle, begun by amateur radio operator Vincent I. Kraft, was the first radio station to be licensed in the Pacific Northwest.

After World War I, the civilian radio stations that had been ordered closed during the war were allowed to reopen. One was Vincent I. Kraft’s amateur station 7AC in Seattle. Kraft operated a small radio parts store in downtown Seattle, and in his spare time played with a small 5 Watt deForest Wireless telephone transmitter, transmitting from his home at E. 68th Street and 19th NE. An antenna hung from a 90 foot tower in the back yard. He soon applied for and received the experimental license 7XC for “wireless telephone” transmission. He moved a phonograph and a piano into the garage adjoining his home, and tacked carpeting on the walls to improve the acoustics. 7XC went on the air on 1110 kc. starting in 1919, transmitting voice and music programs. He played phonograph records, coaxed a local piano teacher into performing, and asked a neighbor boy to play the violin. There was no regular schedule. Every so often he would get a call from one of the few people that had a crystal radio set in Seattle, and he would turn on the transmitter and broadcast so they could demonstrate the new "wireless" to their friends.

In 1921, the U.S. Department of Commerce created a new class of license for radio broadcasting stations. At the same time, a new law was issued that prohibited amateur stations from broadcasting music. So Kraft immediately applied for and received the license KJR, and transferred his 7XC operations to this new license. Unlike its amateur station predecessor, KJR operated on a regular schedule of several hours per day, 3 days a week. Additional transmitting tubes were added to the transmitter to increase the power in stages — first to 10 Watts, later to 50 and finally to 100 Watts in August of 1921.

In a 1962 letter to KJR's management, Kraft laid out his claim for being Seattle's first radio station:

In the special Radio Edition of the P-I dated January 21st, 1925, the early history of broadcasting stations is outlined. Mr. O.R. Redfern, Supervisor of Radio for the Department of Commerce for this area, and who made the inspection of all stations before they could be licensed, wrote an article in which he states categorically that KJR was the first station, being inspected on August 16th, 1921. KFC, the old P-I station, was second on September 12th, 1921. All of the other stations came after that, and all started from scratch, whereas KJR had been operating for some two years under different call letters before the broadcast classification had been created. KJR is unquestionably the pioneer station, and there are quite a few of the old timers around to substantiate this if needed. 2

Until 1923, most radio stations in the United States were required to share just one frequency — 360 Meters (833 kc.) . During these early years, KJR shared the frequency with other stations in Seattle, including the Post-Intelligencer station KFC, Rhodes Department Store's KFOA (later KOL), KTW at the First Presbyterian Church, KDP, KZC, KDZE, KDZT, and KHQ. (most of these stations closed after a few years, and KHQ moved to Spokane in 1925.) Each station broadcast on that frequency for only a few hours a day, and they would agree on a transmission schedule among themselves, as Kraft explained:

We'd hold a meeting of the broadcasters and divide up the time. Mostly it was, you take Wednesday and Thursday evening and I'll take Monday and Tuesday. Radio wasn't an all-day thing. Housewives couldn't operate the sets, we figured. 18

In 1920, KJR broadcast the results Dempsey-Carpenter heavyweight boxing fight. This was not a live audio broadcast — instead, each round’s results were sent from Annapolis via a nationwide telegraph wire hookup, and the results were announced as they came in. Kraft later said:

The first big event to be broadcast by our company was the Dempsey-Carpenter fight on July 2, 1920. This was accomplished with a small 10-watt radio telephone transmitter, and we were more than surprised and pleased to receive reports that the broadcasting of this event was received from points as far away as Anacortes. 1

Soon, Kraft was contacted by the owner of a local music store. He offered to give him all the records he could use, in exchange for mentioning his store on the air. This was his first inkling of radio's future power as an advertising medium.

In 1921, the station moved to 7025 18th Ave NE. In January of 1923, Kraft organized the Northwest Radio Service Company, and transferred ownership of KJR to his new company.

In 1924, the Federal Radio Commission finally authorized more broadcasting spectrum, and many stations received their own frequency assignments. KJR "broke into kilocycles" and moved to its own frequency, 1060 kc., on December 9, 1924, and then increased its power to 1,000 Watts with a new transmitter on January 21, 1925. On March 3 of that year, the station moved to 780 kc., operating with 1,000 Watts from the Terminal Sales Bldg, 1st and Virginia Streets in downtown Seattle.

With more broadcasting hours and a better signal, Kraft made a deal with The Post-Intelligencer to sponsor live music four or five nights a week for several hours. (Almost immediately, The Seattle Times made a similar deal with KFOA.) Live music programming was heard nightly, including Henry Damski's Imperial Orchestra, Herbert Preeg's Concert Orchestra, and Victor A. Meyers and his Orchestra "live from the Butler Hotel". Lectures and other readings helped fill out the broadcast schedule, which was still far short of an all-day affair. 18

In May of 1926, Kraft was quoted in quoted in local newspapers that he was looking for a more favorable location for the KJR transmitter on the north end of the city. “ I am looking for a good site for the two steel towers which will support our new antenna system. We are not satisfied with the results obtained in our downtown location.” Suitable property was located at 15th Avenue Northeast and NE 185th Street in Lake Forest Park, and a new brick transmitter building and two self-supporting towers were constructed to support the typical flat-top “T” wire antenna of the era. A new transmitter raised the station’s power to 2,500 Watts, and the station again changed frequency — this time to 860 kc. New studios were installed on the fifth and sixth floors of the Home Savings and Loan Building at 1520 Westlake Avenue building in June of 1927. Three shifts of operators under the supervision of Chief Engineer John N. Cope kept the new transmitter running, along with another three shifts at the studio. The job of the studio operators was to connect the proper program source to be fed to the transmitter (Studios "A" or "B", or remote sites such as the Olympic Hotel), and continuously adjust the volume to maintain a continuous audio level for the listeners.

Popular names heard on KJR in 1927 included the band leader Henry Damski as Music Director , Pianist Grant Merrill, organist Harry Reed, orchestra leader Abe Brashen, and announcers Thomas Freebairn-Smith, Al Schuss, Chet Cathers and Casy Jones. B.M. Bryant managed the daily affairs at KJR, leaving Vincent Kraft free to build several other stations on the West Coast — KYA, San Francisco, KEX in Portland, and KGA in Spokane. In 1926, he tied all four stations together with leased telephone lines to create what was likely the first radio network on the West Coast.

Financially overextended and more interested in building stations than operating them, Kraft sold his interests in all four radio stations in the Spring of 1928, to Adolph Frederik Linden, who was the co-owner with Mr. Edmund Campbell of the ritzy new Camlin Hotel on 9th Street in downtown Seattle 3, 4. Both men were also directors of Puget Sound Savings & Loan. However, Kraft continued to own KXA in Seattle, which he had recently acquired, and went on to build and operate KINY in Juneau, Alaska in the 1930's. Kraft finally sold KXA, his last station, in 1946.

ADOLPH LINDEN AND THE AMERICAN BROADCASTING COMPANY

Under Adolph Linden’s direction, expansion of KJR and its small network of stations occurred at a rapid pace. Corporate offices were opened in the new Liggett Building at Fourth and Pike Streets, and the money flowed freely to upgrade KJR’s facilities and programming. All of KJR’s programs now originated live from the station’s own studios, and a large program staff was assembled with announcers, singers, a dance band and a symphony orchestra. KJR quickly became the most popular and best-financed radio station in the Northwest, and the staff started calling him “Daddy” Linden, in reference to the wealthy Daddy Warbucks in the popular comic strip “Little Orphan Annie”.

Homer Pope, who started working at KJR as a technician in 1927 and stayed there until 1970, recalled the Linden period in a 1992 interview with the author:

You can’t believe how fabulous it was. We had a 12-14 piece orchestra — they played a couple of hours a day. We had trios, classical, as well as pop, and a lot of people, like Vik Meyers. Vik had an orchestra in Seattle at the Butler Hotel for years, and at the Trianon Ballroom. He traveled around the northwest, and would go to Spokane and to Portland.

Then we had another whole crew in San Francisco, a concert orchestra. It was on three days a week. Herman Kenin with his Orchestra was on every night.

The offices were in the Liggett Building, and our studios were in the Home Savings Building. And a lot of people spent a heck of a lot of money.

We had very little advertising on the air. We had two or three salesmen who worked Seattle — but they didn’t work too hard. There was Baxter’s Shoe Store and a half a dozen others. They really weren’t interest in getting too much advertising locally, it had to be national. We did auditions for Jantzen in Portland, and they said they were signed to start the next summer, and there were several others that supposedly had signed. 10

On November 11, 1928, KJR changed frequencies and raised its power again — this time to 970 kc with 5,000 Watts. The latest Western Electric studio equipment was installed, and equalized telephone lines were used to feed high quality audio to the transmitter.

Soon after taking over the stations, Linden signed an agreement with the Columbia Broadcasting System (later CBS) to distribute that network’s programs in the West. Columbia’s network at that time ended in Omaha, and it was anxious to extend its programs to cover the Western part of the country. The new network was called the American Broadcasting Company — the first of several radio networks to carry that name, and no relationship to the present ABC network. The agreement called for the ABC to pick up Columbia’s programs in Omaha and relay them to the West, mixed with its own programs. Most of the ABC network’s programs originated in Seattle, but KYA and the other stations also originated some shows. Also, on certain nights, Columbia would reverse the phone lines and relay the Seattle programs to the Eastern half of the U.S.7

ABC’s ambitious network program schedule debuted on December 22, 1928, with a three hour program sponsored by the Union Oil Company. On January 6, 1929, new telephone circuits were added to feed additional affiliated ABC stations in Omaha (KOIL), Denver (KLZ), Salt Lake City (KDYL) and Los Angeles (KMTR — later KLAC). The burgeoning network now had eight stations.

The payroll grew to nearly 300 people between the Westlake Square studios and Liggett Building offices. With the high expenses and modest income, some people questioned the source ofthe ABC Network's revenue. In 1928, it finally became apparent where the free-flowing money was coming from. It was discovered that Linden and Campbell had been regularly borrowing money from their own Puget Sound Savings and Loan to keep the station afloat, and to finance their lavish Camlin Hotel project. An agreement was secretly made for the payment of restitution to the Savings and Loan by the two partners in the amount of $1.5 million, and Linden resigned his position as president of the bank — but only to be replaced by Campbell.

Bill Brownlee, Manager of the Camlin Hotel in 1992, talked about his understanding about Linden and Campbell’s financial mess, which also affected the hotel:

BB: My understanding was that the bank began to prosecute Campbell when the bank got wind of the money that they’d absconded with, and they began to prosecute and locked up all their funds, and so they couldn’t do anything, and they finally went bankrupt. The bankruptcy was more predicated by criminal charges than anything else.

JS: So the money was being borrowed from the bank to finance the radio operation?

BB: The money wasn’t being borrowed — it was just being skimmed. There was about a million dollars that just kind of disappeared, and when the balanced the books these guys had taken IOU’s and taken money out, and later tried to say that they had borrowed the money and that it was all up and above board, but it really never was.

JS: That financed the hotel as well?

BB: Yes10

On June 1, 1929 ABC welcomed five additional affiliate stations to the network: WIBO Chicago, WIL St. Louis , WRHM Minneapolis (aka WLB), KFAB Lincoln, Nebraska, and KTNT Muscatine, Iowa. KFBK in Sacramento also joined the network on July 13, 1929. Later that month a press release stated that ABC was lining up a number of stations on the East Coast, including WOL in Washington, D.C.

In 1929 Linden’s ABC promoted a popular series of outdoor summer concerts “under the stars” from a stage built on the University of Washington football field. More than 50 top musicians were brought in from all around the country, including directors Meredith Willson and Alfred Hertz. Live concerts were broadcast three nights a week for several weeks. The concerts were a local sensation and a broadcast success — but they were also the final undoing for the overextended network. Everything came to a screeching halt in August, when Puget Sound Savings & Loan suddenly filed for bankruptcy protection and the flow of depositors’ money to KJR and the ABC network stopped abruptly.7 The leased telephone lines that carried the network’s programs were shut down for non payment. Homer Pope recalled:

That’s what finally folded it. These guys were all union musicians, and they had to get paid. And the telephone company had to get paid for the lines, and they couldn’t do either one. 10

Things quickly started to fall apart without the bank’s financial support. On August 15, 1929, control of the stations was transferred to Ralph A. Horr, a court-appointed receiver. On August 20, the news reached Washington D.C. that ABC had cancelled its plans to extend its network to the East Coast because of financial difficulties. On August 25, ABC gave control of its leased land lines to The Columbia Broadcasting System, so they could continue to feed the network’s Western affiliates directly. On August 26, Columbia announced that it would begin feeding what would later be called the "Columbia Northwest Unit" on September 1. Those stations would be KVI in Tacoma, KOIN in Portland and KFPY in Spokane (later KXLY). Shortly thereafter, Columbia’s head, William S. Paley, would make a deal with broadcast and automobile magnate Don Lee in Los Angeles to add Lee’s stations KFRC and KHJ, and the combined group of Northwest and California stations would form the nucleus of what soon became the Columbia-Don Lee Network.8

Back at KJR, things were quickly falling apart. The network program lines were gone, and the staff and musicians quickly left when their paychecks stopped. A local music store repossessed a truckload of grand pianos. A few loyal employees did what they could to keep the station on the air with no resources. 8 Announcer Thomas Freebairn-Smith went on the air to plead for help, and an old upright piano was donated by a listener. The receiver-in-bankruptcy advanced $50 so the station could buy phonograph records.9 Home Pope recalled the day that the house of cards came crashing down:

We knew it was going to happen, but we didn’t know when, of course. What really broke it first — what did it — was that we couldn’t pay the telephone lines. And that stopped the network. And then we didn’t get paid, and that makes a difference also. When you don’t get paid, people don’t come to work Everything was live at that time, and the musicians all left because they didn’t get paid. Another fellow and I kept it on the air, plus a couple of fellows out at the transmitter, and that lasted from 3 or 4 days. Then an attorney came in and took it over.10

Scrambling for a solution to the financial dilemmas, Adolph Linden was able to negotiate a sale of the radio stations and the ABC network to Twentieth Century Fox. On October 15, 1929, he loaded his family into their Lincoln sedan and they headed for New York to ink the deal, as Homer Pope explained:

It was a big windfall for him — he was going to be able to cash in, pay off his debt, get himself out of trouble and the whole shebang, and so he took off with his wife and kids and drove across the country — he took a long leisure trip across the states to get back to New York to take care of this deal and solve all of the problems. But in the meantime, the stock market crashed, and they backed out. And so the vacation that he took in between was his demise, financially, because they were prepared to go, but when the stock market crashed they decided not to.

The Lindens stayed in New York and tried their hands unsuccessfully in a restaurant business, but in 1931 an arrest warranty arrived from Seattle. Linden was returned to Seattle, and both he and Campbell were charged with failure to make good on the 1928 restitution agreement, and for defrauding shareholders and depositors out of $2 million. Both men were quickly convicted and sentenced to fifteen years at the Walla Walla State Penitentiary. Campbell tried to commit suicide by jumping out of a second story window of his home, but only broke his leg. He served seven years at Walla Walla and later was employed as a credit manager until his death in 1954. Linden was paroled in 1938 and started a small record company in Seattle, Linden Records, where he enjoyed another successful career releasing the music of a number of local jazz musicians. (He reportedly made Ray Charles’ first recording when the still-unknown singer was playing a Seattle night club.) Adolph Linden died broke in 1969. 6

Homer Pope’s post-mortem of the Linden period:

He did it wrong. Instead of starting in New York, he started in Seattle. If he’d have started in New York and done the same thing, I think he’d have made it, or at least held out for another year.

Linden was a nice guy, personally, he was a nice fellow, and he didn’t hold any grief with anybody. He could sit and talk about being against the wall. He said “you give me a 100 watt bulb and a steak, and I can make a rib steak in a couple of hours.” 10

On October 1, receiver-in-bankruptcy Ralph A. Horr took control of KJR, KYA, KEX and KGA. Homer Pope recalled that Ralph Horr also had other motives:

He was a kind of two bit politician and in those days you could do a lot of things that you can’t do today, and there’s a lot of things that you can do today that you couldn’t do then. So Fuller started talking on the air about what a great guy he -- he wanted to run for Congress, and so he spent a lot of time on the air. He later did go to Congress, for one session.

Under Horr’s direction, on December 22, 1929, the remains of the old ABC network resurfaced as the Northwest Broadcasting System, or NBS. - a new regional network serving all three stations with programs originating at KJR. He also set up a real advertising department, and some money was generated to keep the stations operating.

In the Spring of 1930, Horr sold all four radio stations (KYA, KJR, KEX, KGA) out of bankruptcy to Ahira “Hi” Pierce, the owner of Home Savings and Loan. (At the time, KJR's studio were located in the Home Savings building.) Under Hi Pierce, the stations experienced a short rebirth and broadcast some popular, quality programming. But in a strange repeat of history, Home Savings and Loan also went bankrupt, and Pierce also went to jail for misappropriation of funds. 7

Ralph Horr was later successful in his bid for a seat in Congress. He served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from 1931 to 1933, representing the First Congressional District of Washington as a Republican.11

NBC ACQUIRES THE NORTHWEST STATIONS

In October of 1931, all four radio stations and the Northwest Broadcasting System to the National Broadcasting Company. NBC had been operating its “Orange Network” on the West Coast from San Francisco since 1927, rebroadcasting the programs of its East Coast “Red Network” in the West. The Northwest Orange Network affiliates were KOMO in Seattle, KGW in Portland and KHQ in Spokane. In the East, NBC also operated a second network called the “Blue Network”, and it planned to set up a second West Coast network to bring its Blue Network programs out West, to be called the "Gold Network". So, on October 18, the inaugural program of the NBC “Gold Network” was broadcast from New York. The stations on the new network were: KPO San Francisco, KECA Los Angeles, KJR Seattle, KEX Portland and KGA Spokane. Additionally, KFSD in San Diego and KTAR in Phoenix could air programs from either the Orange or Gold Networks.8 (KYA in San Francisco operated for a short while as a part of the "Brown Network", but that was shortly dissolved. NBC sold KYA to the Hearst Publishing Company in 1934.)

The Gold Network did not even last for two years before it was shut down by NBC. This was at the depths of the depression and the cost to lease a second set of program lines on the West Coast was very high. So on April 1, 1933. NBC announced it was shutting down the Gold Network, which it also called the “KPO Network” or “Secondary Network. They would instead transmit these programs to the West Coast over KPO in San Francisco, which had just installed a new 50 kW transmitter. KGA, KJR, KEX and KECA would now have to produce their own programs locally. The original Orange Network continued to operate over KPO, KGO, KFI, KOMO, KGW, and KHQ. On occasions, the four disenfranchised local stations would occasionally carry a few Orange Network programs, but only when local programs preempted their broadcast on the usual stations.

A 1933 NBC press release stated:

An economic saving without sacrificing the service to listeners is the motive of the Pacific Division’s change in network policy, according to the NBC Western Head Don Gilman. With KPO’s increase of power, it will be possible for clients purchasing time on it as a single station to obtain more intensive coverage of the Northern California area than heretofore.

According to Homer Pope, NBC also had a plan for getting the operating expenses of the four stations off its books:

NBC came up with the idea that they could lease these stations to the affiliates in each town — like in Seattle they had KOMO — so they leased KJR for a dollar a year. This was during the depression — things were rough. The affiliates didn’t have any choice, so they said “yes”. And we lost money for I don’t know how many years. About 1933, KOMO took over KJR and operated it. We only had one network at that time, so KJR was independent, but KOMO operated them.10

KOMO (Fisher Blend Station, Inc.), NBC’s main Seattle affiliate, was located on the seventh floor of the Skinner Building, 1326 Fifth Avenue, and so KJR moved in with KOMO in February of 1933. KOMO’s studios were expanded to accommodate both stations. The same arrangements were made in Portland, where KEX was leased to KGW (The Oregonian Publishing Company), and in Spokane where KGA went to KHQ (Louis Wasmer, Inc.) The ownership of all three stations was officially transferred to the affiliates over the next few years.8

NBC now had a pair of affiliated stations in each major city on the West Coast: KOMO/KJR in Seattle, KGW/KEX in Portland, KHQ/KGA in Spokane, KPO/KGO in San Francisco, and KFI/KECA Los Angeles.

THE BEGINNINGS OF KOMO

At this point, let’s go back and pick up the story of KOMO from its beginnings until it joined with KJR in 1933.

It began as KFQX in 1924, operated by the American Radio and Telephone Company, under the ownership of Roy Olmsted and Alfred M. Hubbard. Roy Olmstead (1886-1966), was a formal Seattle policeman and the very successful operator of an “import/export liquor business” — buying alcohol spirits in Canada and delivered them to Mexico. In reality, Olmstead was Seattle’s biggest bootlegger, and most of the products bought in Canada were really destined for the United States, where prohibition was in full swing. His business was reportedly the biggest single employer in the Seattle area, grossing over $200,000 a month in liquor sales. It’s not hard to see where the money to operate Olmsted’s new “hobby” radio station was coming from.

In 1924, Roy Olmstead divorced his wife and married Elise Campbell, a young English woman he had met in Canada. They bought a large mansion they called the “Snow White Palace” at 3757 Ridgeway Place in the posh Mount Baker district of Seattle. Shortly afterwards, Olmsted joined forces with Alfred M. Hubbard, a young radio engineer. Together they formed the American Radio Telephone Company, and Hubbard set to work building a 1,000 Watt transmitter which was installed in a spare bedroom of the Olmsted home. Elise Olmsted became a regular on the radio station, hosting a nightly program of children’s bedtime stories. However, prohibition agents were suspicious that Mrs. Olmsted’s broadcasts were really coded messages sending instructions to the Olmsted rumrunner boats in the Puget Sound.

Roy C. Lyle, the Prohibition Bureau Administrator for Washington State, and Assistant Chief William M. Whitney, were assigned the difficult task of shutting down the Olmsted operation. In exchange for a job offer to become a prohibition agent, Olmsted’s engineer and business partner, Alfred M. Hubbard, became a secret informant for the agency. Drawing from Hubbard and other informants plus information collected from wiretaps, Whitney raided Olmsted’s home on November 17, 1924, shutting down the radio station and arresting Olmsted, his wife and fifteen guests.

The Federal Grand Jury returned a two-count indictment against Roy Olmstead and 89 other defendants on January 19, 1926 for violation of the National Prohibition Act and conspiracy. It was the biggest liquor violations trial in the country's history under the Eighteenth Amendment. Olmstead was sentenced to four years in the McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary and fined $8,000 and was released in 1931.

BIRT FISHER AND KTCL

KFQX had been off the air for four months in March of 1925, when Birt F. Fisher and the American Radiophone Corporation leased the station for a year with an option to purchase. The call sign was changed to KTCL, for “Know The Charmed Land”. Fisher moved the transmitter to 29th Avenue West and Drahvus Street on Magnolia Bluff, where he installed a new building and an antenna suspended between two 10 ft. wooden poles. Studios were located in the New Washington Hotel in downtown Seattle. KTCL went on the air April 29, 1925, broadcasting five hours a day, sharing time on 360 meters (833 kc) with several with other small Seattle radio stations. The station broadcast each day in the early afternoon and again in the evening with programs such as the Western Giant Orchestra directed by Warren Anderson during the week, the Sentinel Program on Saturday nights, and theervices of the First Church of Christ Scientist on Sunday nights.

Fisher operated KTCL on a modest budget, and was always underfinanced and short of cash. He hired a salesman and secretary, and did his own announcing. At the time, transmitter tubes were a big expense for any radio station. Fisher’s 1,000 Watt transmitter required eight Western Electric 250 Watt tubes, which cost $110 each and were good for 300-400 hours of operation. Fisher never had enough money to buy more than two tubes at a time. But as soon as he bought two new tubes, two of the old ones would burn out , leaving him back where he started. In April of 1926, KCTL was evicted from the New Washington Hotel, and the station was off the air for a few days while Fisher moved the station to the Home Savings and Loan Building on Westlake Avenue (this would be the location of KJR’s studios a few years later). 9

However, the worst of Fisher’s problems were yet to come. As mentioned, Roy Olmsted was convicted of liquor law violations and fined $8,000. In order to raise the cash to pay the fine, Olmsted sold KCTL on May 21, 1926 to Vincent I. Kraft, the owner of KJR, for $10,000. Kraft told the newspapers, “There will be no change in the programs of KTCL. Mr. Fisher will continue to operate the station under his lease, which still has several months to run.” He announced big plans once the Fisher lease expired, but denied any plans to move KTCL to Olympia.

Faced with the imminent loss of the station, Fisher scrambled to find a solution to his dilemma, his main problem being a lack of financing. He knew that Oliver David (O.D.) Fisher (no relation to Birt Fisher), the managing owner of Fisher Flouring Mills, Inc., was a big radio fan, and so he approached the Fisher family to seek financing for his radio operation. (O.D. had first become enthralled by radio when his nephew William Warren built a crystal receiving set at his home on Capital Hill.) O.D. and his brother Will agreed to put up the money to form Fisher’s Blend Station, Inc., which with 66% ownership by the Fisher brothers and 34% by Birt Fisher. The plan was to build a brand new radio station and transfer the KCTL operations to the new station when Fisher’s lease expired. Beginning in November, a three story concrete building was constructed on the West Seattle waterway, behind the Fisher flour mill, and a 1,000 Watt factory-made transmitter was installed. Two tall wooden poles would support the antenna. Studios were built in the 303 Westlake Square Building. The station would debut on 980 kc. at the end December of 1926. On November 21, a newspaper article reported that :

Seattle is to have a new and powerful broadcasting station Construction has begun on the building and towers, located on Harbor Island. The plant will be operated by the Fisher Blend Stations, Inc. Wallace Fisher has been named president of the radio operating company. It is to be a standard Western Electric Company station of 1,000 Watts, the only one of its kind on the coast North of Portland. The transmitter will be on Harbor Island near the Fisher Flourinjg Mills plant, where towers and the new building are now under construction. The main studios will be in the Metropolitan Center.

In September, Fisher applied to change KCTL’s call sign to KOMO. He said it didn’t stand for anything — he just liked the sound of it. He wanted to get rid of the KTCL call sign, which had been linked to bootleggers in the papers. The government agreed to let him transfer the KOMO call sign to the new station when it went on the air.

At the same time, Kraft and KJR began causing interruptions to the remotely operated KTCL/KOMO transmitter. On October 2, 1926, Fisher sued KJR and eight other defendents, including Vincent Kraft, Roy Olmsted and Alfred Hubbert. The suit stated that KJR had violated the contract that allowed KOMO to operate by remote control. The suit also complained that Olmsted had sold stock in the station to KJR in violation of Fisher’s option to purchase the station. An injunction was handed down a month later that prohibited KJR from interfering with the operation of KOMO.13

The new KOMO went on the air at 3 PM on December 31, 1926. However, Fisher’s lease of the old KTCL was still in force for a few days at beginning of 1927, and so for a short period he operated both stations at once. (The call letters of KTCL-KOMO had been changed again, to KGFA, which allowed the new station to assume the KOMO call sign. Kraft took over operation of KGFA in early 1927, and changed the call sign again — to KXA.9

The new KOMO’s inaugural broadcast was an all-day radio extravaganza involving over 250 people, including music performed by the station’s new full-time staff orchestra. KOMO was soon broadcasting an unheard-of 14 hours a day to Seattle audiences. All of KOMO’s programs were live from the start, and the station was reported to be the largest employer of musicians in the state.

To fund the operation of the station, O.D. Fisher had formed a new corporation named the Totem Broadcasters, owned by twelve of the largest businesses in Seattle. Each business committed to sponsor a portion of the unsold air time, in exchange for on-air mention of the company’s contribution. Fisher’s Blends Flour was also a regular advertiser on the new station, and sales quickly increased. 9, 14

In 1927, the KOMO studios were moved to the Cobb Building, located at Fourth and University Streets in downtown Seattle. The station quickly become the most popular in Seattle, with a staff of 65 producing fourteen hours of live programs a day. The Federal Radio Commission would change KOMO’s dial position several times over the next few years — first from 980 to 1080, then back to 980, then to 920, 970 and finally back to 920. When most radio frequencies were changed after the 1941 NARBA agreement, KOMO went to 950, while KJR moved from 970 to 1000. In 1944, KJR and KOMO (then under the same ownership) swapped frequencies, which put KOMO on its present frequency of 1000 kc.

In February of 1927, the National Broadcasting Company extended an invitation to KOMO to send a representative to New York to consider joining the network. O.D. Fisher made the trip, and returned a week later with an affiliate contract in his hand, beginning a long association between KOMO and NBC. On April 5, 1927, KOMO carried the debut program of NBC West Coast "Orange Network", with its programs originating from San Francisco.

COMBINED KOMO-KJR OPERATIONS

As was explained previously, KOMO took over the operations of KJR from NBC in 1933. KJR was leased for a dollar a year to Totem Broadcasting Company and Fisher Flouring Mills, Inc., and Birt F. Fisher became the manager of both stations. (One can only imagine the satisfaction that Birt Fisher felt in this turn of events. Six years ago he had been involved in a legal battle with KJR to keep his station on the air, and now he was manager of both stations.)

Bigger studios were now needed, and the KOMO and KJR operations were combined that year into new studios on the seventh floor of the new Skinner Building on 5th Avenue (Now home to the Fifth Avenue Theatre). KJR’s slogan became “Seattle’s Pioneer Station”. Because the NBC Gold Network had been shut down earlier in the year, all of KJR’s programs originated locally. This turned the newly KOMO-KJR studios into a busy place for several years.

In 1936, NBC once again established a second Pacific Coast network. Multiple broadcast-quality phone lines were now available across the Rockies, and so it was possible for the first time to hear the original programs of both the Red and Blue networks from New York, Chicago and other cities, instead of the re-creations that had previously been performed in San Francisco. The original NBC "Orange Network", with the exception of KGO, became the Pacific Coast Red Network. KGO, along with KECA Los Angeles, KFSD San Diego, KEX Portland, KJR Seattle, and KGA Spokane formed the new Western Blue Network Additionally, KTAR in Phoenix and KMED in Medford, Oregon, could elect programs from either network. The West Coast Blue Network was inaugurated with the broadcast of the Rose Bowl Game from Pasadena on New Year's Day, 1936. KJR became the Seattle Blue Network affiliate, and so was once again a major radio presence in the Seattle area..

Also in 1936, work began on the construction of a new 570 foot Truscon self-supporting tower at the KOMO transmitter location at 2600 26th Street SW on the West Seattle waterway. KOMO went on the air from the new building in March. A new wing was added to the building in September, and KJR moved out of its Lake Forest Park site and into the KOMO facility on December 8.8 The entire investment, including the building, tower and two new 5 kW transmitters was said to represent a $223,000 investment by the Fishers, including $10,500 for the tower itself.19

In 1941, Fisher’s Blend Station finally purchased KJR outright, ending its eight year lease of the station. The timing was good, according to Homer Pope: As soon as they sold it, they started making money fast. This is about the time that radio started to take off.10

Also in 1941, KJR moved from 970 to 1000 kc., as part of the massive shift of AM frequencies that occurred in North America under the NARBA treaty. On May 7, 1944, the Fishers swapped frequencies between its two stations, giving KOMO the better 1000 frequency and moving KJR to 950.8 Thus both stations were finally on the frequencies that they occupy to this day.

The following year, the F.C.C. passed a new duopoly rule that prohibited a single entity from owning two radio stations in a single city. This forced the Fishers to divest themselves of one of their stations, and so the Fishers sold KJR to Birt Fisher. He operated the station only two more years before selling KJR to Marshall Field Enterprises in 1947.

In 1948, KOMO inaugurated operations at 50 kW from a new directional transmitter site on Vashon Island. (KJR remained at the West Seattle location until 1996.) A new KOMO studio building was also inaugurated that same year at the corner of Fourth and Denny Way, across the street from today's Space Needle, which gave additional room for studios of the planned KOMO-TV station. (The TV station was inaugurated in 1953, broadcasting on channel 4, affiliating with the NBC Television Network. Both the TV and radio stations changed their affiliation to the ABC network in 1958.)

KOMO radio continued to broadcast its conservative mix of network and local block programming until the early 60’s, but by 1964 had adopted an MOR (“Middle of the Road”) adult music format. Popular morning personality Larry Nelson joined the station in 1967 and was a familiar voice on the station until 1997. Norm Gregory joined the station in 1984. Bob Blackburn called the play-by-play broadcasts of the Seattle Supersonics, and KOMO originated the University of Washington Huskies sports broadcasts. The station's format eventually evolved into a news talk format in the 1990s,and Pat Cashman moved over from KIRO-FM in 1999. In 2002, the format was again changed, this time to an all-news format with mornings hosted by former KIRO AM news anchor Bill Yeend. KOMO also became the originating station for Seattle Mariners baseball play-by-play broadcasts in 2002.14 The station continues to be a major force in the Seattle radio market.

INDEPENDENT AGAIN, KJR THRIVES

Meanwhile, KJR continued to grow and prosper as an independent station in the 1950’s and 60’s. On August 13, 1952, Marshall Field Enterprises sold KJR to the Mt. Rainier Radio and Television Broadcasting Corp., principally owned by Ted R. Gamble of Portland. The company also purchased KOIN AM/FM in Portland at the same time. The new owners were interested in television, and KJR had recently filed an application with the F.C.C. for the Seattle channel 7 TV assignment, but they lost their bid for the channel to KIRO Radio.8 They were more successful in Portland, however, where KOIN-TV soon reached the airwaves.

After their unsuccessful Seattle TV bid, KJR and the Mt. Rainier Radio and TV Broadcasting Corporation was sold again, this time to Lester M. Smith and John Malloy, for a reported $800,000. Malloy was the owner of KVSM in San Mateo and KROY Sacramento, both in California, and Smith was the manager of KVSM after starting his career as an NBC page boy in New York. Smith's arrival in the Northwest began a 44 year broadcasting dynasty that would also involve KXL in Portland (purchased in 1955), and KNEW in Spokane (which became KJRB), and stations in Cincinatti and Kansas City, and with Smith manning the helm for the entire period.

Shortly after buying the station, Smith made a masterful financial move — he sold KJR's West Seattle waterway property in 1954 to the Port of Seattle , with a 40 year lease-back of the tower site for $850,000, recovering the entire purchase price of the station.20 (The clock would finally run out on the lease in 1994, however, obligating KJR to move its transmitter to Tacoma.) The studio were moved to the transmitter site on the West Seattle waterway in 1955.

KJR’s programming at this time consisted of network programs like "The Grouncho Marx Show" and "Duffy's Tavern", mixed in with some local programming featuring Seattle personalities like Ivar Haglund. However, Smith had observed the power of the new rock and roll music, which was seeing great success in cities like Dallas and Kansas City, and so he decided to try it on KJR. Disk jockeys like Bob Salter and Dick Stokke were playing the new music 24 hours a day, pausing only for occasional news and weather reports. As the Northwest's first rock and roll radio station, the ratings quickly soared, and the format was here to stay for the next 20 years.

On June 7, 1958 Smith and Malloy sold their interest in KJR, KXL and KNEW to siinger Frank Sinatra and actor Danny Kaye for $2.5 Million. The station was now licensed by Essex Productions, Inc. & Dena Pictures, Inc., a joint venture doing business as Seattle, Portland & Spokane Radio, Inc. (Essex Productions was owned by Sinatra and Dena Pictures was owned by Kaye.) Les Smith became the General Manager of the station group. 17

KJR’s fledgeling rock and roll format took on new life in 1959 when Smith hired a young disk jockey named Pat O’Day. He became a sensation with the area’s teenage audience by combining rock and roll hits with a cast of crazy on-air characters. He was soon joined by other popular disk jockeys such as Larry Lujack, Lan Roberts, Emporer Smith and Dick Curtis . The station was known for broadcasting crazy on-air promotions like the World’s First Slug Race Festival and the World’s First Buffalo Chip Throwing Contest.

By March of 1960, the station’s ratings zoomed to number one with an amazing 37% of the Seattle audience. Advertisers who had been reluctant to associate themselves with the new music started lining up at the door.

On October 14, 1964, Sinatra sold his interest in the stations to Danny Kaye and Les Smith, and they formed Kaye-Smith Enterprises, with Kaye having majority ownership. (Smith bought out Danny Kaye in 1981.)17

Pat O’Day became the Program Director, and in 1969 moved up to Station Manager. He left the station in 1974, and Shannon Sweatte followed him as Station Manager. Popular KJR air personalities in the late 60s and 70s included Charlie Brown, Gary Shannon, Norm Gregory and Gary Lockwood.

In 1980, at the height of its popularity, Metromedia purchased KJR from Kaye-Smith Enterprises for $10 million — a healthy profit for a station acquired nearly for free. But the heyday of AM rock and roll radio was nearing an end, and just four years later, KJR was sold for only $6 million to Ackerley Communications, headed by billboard mogul Barry Ackerley. He had just recently acquired the Seattle Supersonics basketball team, and wanted to own a radio station so he could carry the games on his own station and sell all the advertising around the games.19 The studios were moved from West Seattle to 190 Queen Anne Avenue North in 1988, and the Top 40 format was dropped in favor of Classic Hits, an indication of the changing and aging AM radio audience. Four years later the format would change again, this time to Sports Talk, as KJR became an affiliate of ESPN Radio.

KJR finally was required to face the ticking time bomb of Lester Smith’s leaseback of the KJR West Seattle property to the Port of Seattle. The lease finally expired in 1994, and the Port asked KJR to vacate the property. As the Port had grown over the years, with the building of large container loading cranes on the water’s edge, there were increasing complaints of electrical shocks to crane operators and workers, caused by their proximity to KJR’s 5,000 Watt antenna. The station’s management solution was to apply to the F.C.C. for a power increase to 50,000 Watts and move the transmitter to new property on the Duwamish Waterway a few miles to the south, a site provided by the Port of Seattle. A new directional antenna system was built at great expense, and the station went on the air from its new location in 1996. However, the complaints experienced at the Port were now replaced with a new set of problems. The station’s new 50,000 Watt signal was interfering with the telephone and electronics systems of the large and influential industrial plants that neighbored the new tower site. Complaints to the Port Authority resulted in KJR being evicted again, and a search for yet another site was begun. After considering a number of options, the KJR transmitter was moved to Tacoma in 1999 and combined with co-owned KHHO 850 (formerly KTAC). The historic Truscon KOMO-KJR tower at West Seattle, which had been a waterfront landmark since 1936, was finally dismantled in 2000.

Ackerley Communications sold a majority ownership in KJR to New Century Seattle in July of 1994 for $30 million, showing a significant profit due to the station’s recent F.C.C. authorization to increase power to 50,000 Watts, and because of the new buying frenzy that was taking place in radio following the elimination of the F.C.C.’s ownership limits, a move that changed the face of American radio. Michael O’Shea was the new President of KJR and a part-owner of New Century, but Barry Ackerley bought back O’Shea’s shares in 1998.

In 2001, Clear Channel Communications acquired the Ackerley group of stations, including KJR. Clear Channel was not satisfied with the strength of the signal over Seattle, and so a third transmitter site change was made in 2004 — this time combining with KGNW 820 from that station's site on Vashon Island.

KJR ended the 20th Century as KJR 95 Sports Radio, an AM radio powerhouse with an 80 year history of service to the Puget Sound region.

FOOTNOTES:

1 Statement by Vincent I. Kraft on January 21, 1925, on the occasion of KJR's increase to 1,000 Watts.

2 Seattle’s second station was KFC (The Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s station) which debuted Sept. 12, 1921

3 Letter from Vincent Kraft date 6/18/62.

4 The name of the CAMLIN Hotel was a contraction of the names Campbell and Linden. The hotel continues in business today under the same name.

5 HistoryLink.org

6 Wikipedia: Camlin Hotel

7 Puget Sound Savings and Loan eventually closed its doors in 1931.

8 www.pdxradio.com: “NBC and KGW — Networks Connect the West” by Craig Adams

9 David Richardson, Puget Sounds (Seattle: Superior Publishers, 1981)

10 John Schneider interview with Homer Pope and Bill Brownlee, 7-15-92.

11 Wikipedia

12 Olmstead, Roy (1886-1966) -- King of King County Bootleggers, By Daryl C. McClary. www.historylink.org

13 Various contemporary newspaper articles saved in a bound KCTL/KOMO scrapbook.

14 KOMO Radio History — Wikipedia.

15 A KJR AM Modern History — prepared by the Washington State Association of Broadcasters, 2002.

16 Photo credit: Museum of History and Industry, Seattle

17 http://stumptownblogger.com

18 Don Duncan's Driftwood Diary — Seattle Post-Intelligencer, date unknown.

19 Letter to author from Kelly D. Alford, 2010.

20 "From what I know about the Lester Smith/Port of Seattle deal, the Port was going to force eminent domain rights and boot KJR from the West Seattle west waterway location at a much lower amount than their $850,000 offer, so Lester really didn't have a choice. I confirmed what Lester told me via various memos that I found between he and the Port of Seattle. Originally, the lease was to have been 99 years, but Les agreed to 50 years for the higher purchase price." - Letter to author from Kelly D. Alford, 2010.